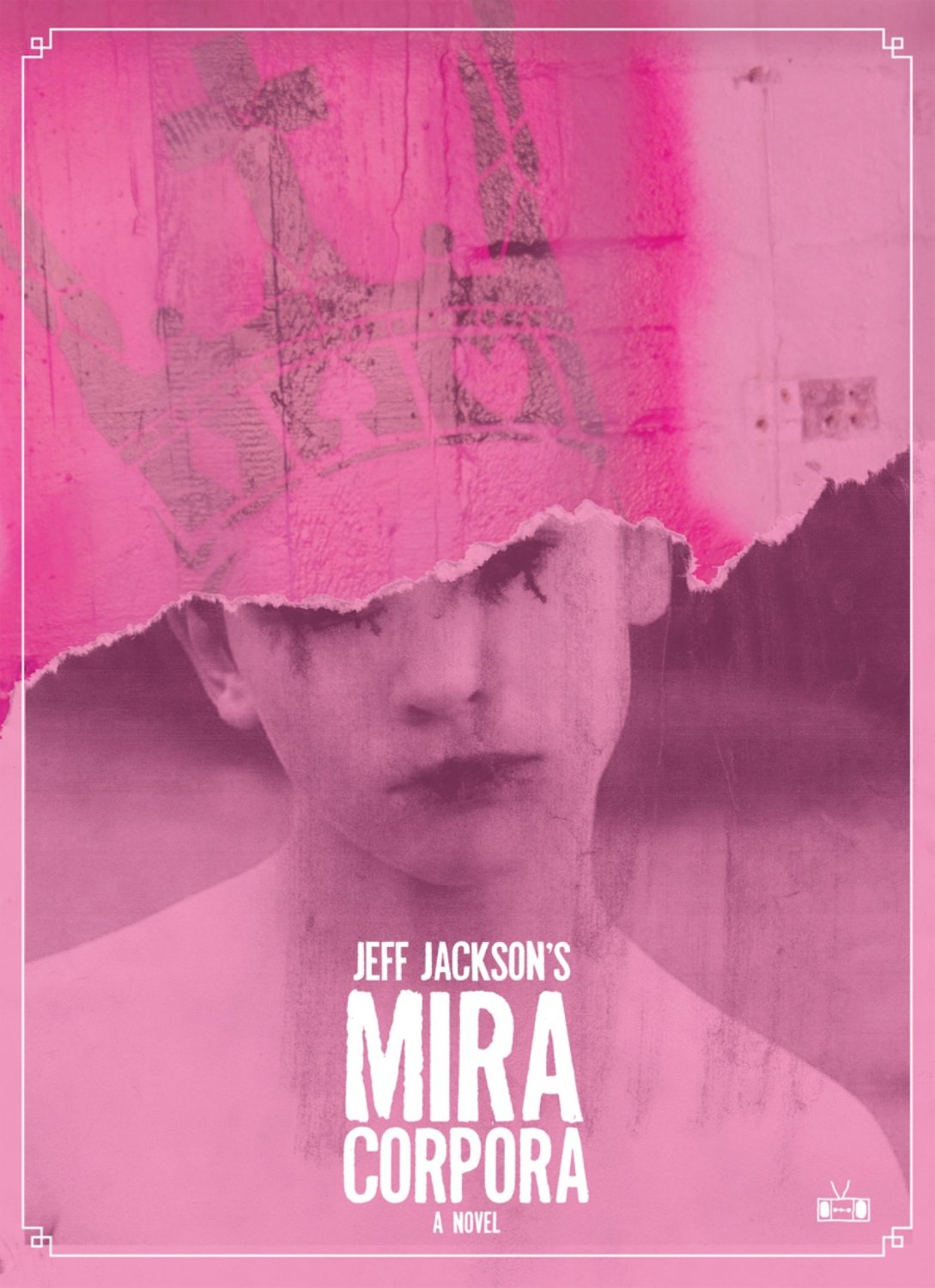

Two Dollar Radio, 2013

Jeff Jackson’s debut novel Mira Corpora is a study in defiant contradictions. As its jacket description states, it’s a coming-of-age story for people who hate coming-of-age stories. In addition, it’s a book that clearly states an autobiographical bent while incorporating fantastical, creepy elements, but without making the reader stop to wonder what is real and what is imagined. An astute reader will note several passages that underline, highlight, and wink at critiques of contemporary fiction, but this isn’t a novel that wants to be defined as an answer to the tired people who emerge from their caves every so often to bemoan an imagined stagnancy in contemporary writing. One could be tempted to say that Mira Corpora attempts to rewrite the rules of fiction, but for as original as it is, it really is just a wonderful, entertaining book that reads very quickly, and yet, upon reflection, encompasses so many journeys and ideas.

The novel tells the story of Jeff Jackson, a young man who narrates the story of his life from ages six to eighteen. An opening note states that the stories were taken from childhood notebooks. It begins with his mysterious participation in a hunt in which he ends up becoming the bait. The opening section was originally published in Guernica and works as both a stellar and ominous introduction as well as its own original morality tale:

Of course there are things before the first things: A stone farmhouse, warm meals served on white plates, a large room filled with narrow beds tucked with wool blankets. But this hunt is my beginning. The kids fanning through the forest. The slow-motion ballet of soundless steps. The silent chorus of raised rifles.

The narration then shifts to awkward interactions with Jackson’s mother, after which he leaves the house, teaming up with a group of artistic, wandering teenagers on the run from a gang of murderous, perverted truckers. Upon leaving this group, Jackson becomes a homeless teen on a city street, in possession of an underground cassette tape. Along with two other youths, he joins a search for a reclusive rock musician, who is still performing, but in a most unexpected venue. Once this discovery is made, he finds himself held captive as a male prostitute for a wealthy older gentleman. This leads to a final escape and a return to his mother’s house. These various plot developments move the story back and forth between rural to urban settings, and from despondency to self-discovery. Taken at face value, these movements are tropes of classic fiction: the character moves, grows, and returns home. The transitions I’ve used in this summary are not unlike the transitions within the novel; Jackson is not interested in building up bridges from scene to scene. The pages move sharply, but in a very compelling fashion. As with the meta and autobiographical undertones, it’s written very carefully to minimize and soften the abrupt shifts.

Jackson’s writing is at times, quite simply beautiful. His narrative voice is strong and visual, creating evocative mental images (Jackson is best known as a playwright), with an emphasis on strong adjectives and excellent descriptions:

The apartment opens. A tall man in a shiny black ski jacket and hand-me-down grimace lets people inside.

It’s the skinhead girl. She adjusts the tips of her horned-rimmed glasses as if trying to bring my curious activity into better focus. The rest of the road is empty, but the other kids must be watching, too. Hosts of them are squatting in the surrounding derelict bungalows. It’s easy to imagine their round faces, like balls on strings, suspended in the dirty windows.

Given Jackson’s play-writing background, I found myself paying deeper attention to his use of dialogue, and while I’m not a scholar of contemporary theater, I did note the dialogue’s mix of sparse, almost perfunctory information and its sometimes mythical, loaded qualities. For the most part, the dialogue tells the reader everything from a literal standpoint, but as I mentioned above, there are pieces and paragraphs that contain a touch more information, enough to hint at several wider possibilities and meanings.

“But why me?”

“You’re on the street,” Lena says. “You know what’s really happening.”

Jackson is stunningly talented, and Mira Corpora is as strong a debut as any thus far in 2013. This novel has some clear influences and reflections (Denis Johnson comes to mind), yet is wholly original and creates its own ideas and mythologies. Perhaps there’s a classroom debate within these pages and the reader should be wondering what is based on actual events and what is completely fictionalized. But this is terrific writing with enough imagination and scenery to render those arguments useless. Jackson achieves what is the ultimate goal in literary art: he creates unbelievable, sometimes fantastic, exaggerated worlds in order to ask and answer the ancient questions: Who are we? Where are we going? From where do we come? For as much praise as Jackson has received early on, Mira Corpora is still on the fringe and is grounded enough to toe the line between experimental and standard literature.

+++

+