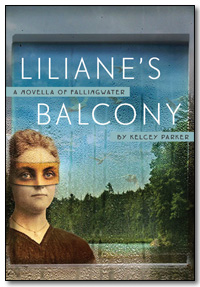

Rose Metal Press, 2013

In Kelcey Parker’s Liliane’s Balcony, A Novella of Fallingwater, Frank Lloyd Wright’s house, built for Liliane and Edgar Kauffman, is more than mere setting—it is a haunted, live place. In the prologue, which recreates Liliane’s state of mind at the end of her life, she is tormented by thoughts of her husband’s latest lover, who works in their house as her husband’s nurse, and as her thoughts circle, Liliane slowly takes a series of “pain pills.” She is tormented, too, because she can’t hear the sound of water that falls from beneath the house, the usual soothing backdrop of her life.

And there, below her, not so much like an old friend (of which she has many) but a best friend (of which she has none), yes, there it is: a moving surface, a moonlit triangle, hypotenused by the rock’s edge. That edge marks the point of transformation from stream to spray, from slipsong to scream. Schäumt er unmutig / Stufenweise / Zum Abgrund. She can hear Goethe’s words, Schubert’s chorus, but she can’t hear it, the water. Darkness covers sight, not sound, yes? She looks up, away from the silent water, and hears the sharp whistle of a hawk perched somewhere in the surrounding fortress of trees, upside-down brooms that sweep the sky.

The sky is a constellation of pain pills. Liliane reaches out her hand and squeezes a cluster into her fist. She puts one in her mouth, swallows it, and thinks of water. Where is the voice?

She needs the sound of the water, and the section doesn’t end until she hears it. She “plucks another pain pill from the sky” on her way to a fatal overdose.

In following chapters, the reader assembles pieces of the couple’s life, including letters from the young Edgar, her husband, which Parker transcribed from his real letters to Liliane. These letters and other short sections (some as brief as a sentence, the longest only several pages) give the novella a mosaic feel, as the pieces of their lives assemble. In chapters interspersed with those focused on Liliane and Edgar, a group of visitors tours Fallingwater and experiences an assortment of hauntings. No matter who is speaking in the book, the house is the locus for the past and all of the present-day action, and the waterfall soaks the novella with liquid sounds. Parker skillfully builds a case, in translucent prose, that Fallingwater is an extension of Liliane, so much so that the more attuned visitors to the house can sense her ghost and are changed by their visit to Fallingwater.

The contemporary stories of the tour group members offer reprieve from the bitterness and doom of Liliane’s story. Told from each group member’s perspective, these pieces give us a kaleidoscope of experiences and viewpoints. The novella’s trajectories toward the transcendent, either through a character’s experience of the house or from Liliane’s ghostly meditations, are balanced by refreshingly prosaic observations. For example, Janie, on Liliane’s cantilevered balcony, thinks of Emerson’s writing:

On the balcony, supported by, from what she can tell, nothing, Janie thinks of Emerson, his transparent eyeball. This must be something of what he meant, something about Universal Currents or Universal Being and currents flowing through. She’ll have to reread it. But she remembers the bit about the eyeball and seeing all, being nothing. Over the balcony’s edge is the waterfall, and she definitely feels like nothing, just a being who sees water, trees, rocks.

From the opening of the novella, Parker’s clear prose carries the reader along the liquid plaits of a braided book. Like water, the words are translucent and conduct light. Parker has created a book in which Fallingwater, Liliane’s ghost, and a group of visitors illuminate each other to mutual benefit, and in which she suggests the idea that a person’s soul can meld with a place. The novella’s confluence of voices flow and reflect like water, and they are set off by liberal white space between each brief section, a backdrop of silence from which Parker’s poetic prose can speak.

+++

+