Restless Books, 2016

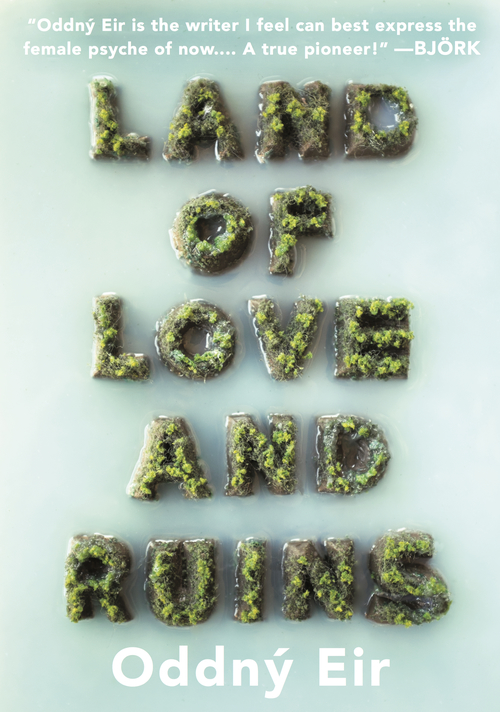

The Icelandic writer Oddný Eir is difficult to pin down: philosopher, visual artist, archaeologist, publisher, historian, and environmental activist. She’s a brilliant thinker, diving into as many interests as one person possibly can. Land of Love and Ruins is a reflection of her multifaceted nature. While labeled as fiction, the book is enjoyably outside genre and would fit best on a memoir/prose poetry/philosophical exploration shelf at the bookstore. One of a series of pseudo-autobiographical books by Eir, Land of Love and Ruins was nominated for and won numerous awards, including the 2012 Icelandic Women’s Literature Prize and the 2014 EU Prize for Literature. As the Nobel Committee loves to remind us, American Literature is an overly insular world—Dylan be damned—so the growing accessibility of texts such as Eir’s is a welcome change, especially when those texts challenge the norms of genre and form. And beyond Eir’s experimental leanings, Land of Love and Ruins is blurbed by Björk, which is about as sparkling an endorsement as any author could wish for.

The book follows Eir through a series of diary entries, each labeled with a location and a description of the day (“Reykjavík, Ash Wednesday,” “Paris, Embers Day, full moon,” etc.) While these journal-like chapters have a meandering nature, a strong recurring theme is Eir’s search for balance in her relationships: how do we please the opposing needs of privacy and intimacy, solitude and connection? How do we guard our inner lives while also making ourselves emotionally available to those we care about? To answer these questions, Eir embarks on a long trip through Europe and the Icelandic countryside, tracing the roots of her ancestors. Along the way Eir explores the connections between people, land, and home, often spinning her thoughts into wonderfully poetic philosophies and observations. One such example from Eir’s visit to her grandmother’s old home: “It’s strange to have come to a place I’d heard so much about. I even feel farther from the place now, when I’m here inside it, than when Grandma described every little nook and cranny, all its patterns and colors, as if she were describing the emotional life within the house at the same time.”

The two characters Eir attempts to maintain a healthy connection with are given pet names in the book: Birdy—her ornithologist boyfriend—and Owlie—her archaeologist brother. Eir is a relatable and fickle partner, trying to grow into her relationships without being smothered by them. Throughout Land of Love and Ruins, special attention is paid to the bond between siblings. A comparison is often drawn between Eir and Owlie’s relationship and that of the writers William and Dorothy Wordsworth. Eir goes so far as to visit the Wordsworths’ home: “I had to come here and see the siblings’ house, find out about their life together, discover whether the dwelling they shared might reveal something of the closeness of their relationship. If I could learn from it.”

On the sentence level, Eir’s writing is defined by a zuihitsu-like lyrical prose: “My thoughts go round and round. In a grilled green mosquito coil in turquoise and orange Ephesus, where temples, churches, and mosques stand side by side.” Ideas and images are the main drivers here, and Eir always follows them to whatever obscure corner of the mind they lead. The more metaphorical, twisting diary entries could frustrate some readers. If you’re interested in strong central plot threads with payoff, this is not the book for you. But a reader who appreciates Eir’s vibrant point of view will be delighted with sentences that sound so good you don’t care where they’re going:

My new friend, that rookish life and soul of the party, is so arrogant. Or is just a hunchback leper, a fosterchild of the moor, a suppressed jack-in-the-magma who runs for shelter inside the city because a train crashed near the outdoor chessboard next to the bathhouse, just as the cockaloric, swaggering archcleric lit himself on fire and an earthquake shook the mosaic-adorned buildings, causing the Carnival to come crashing down like shattering glass.

Eir is never afraid to write her naked thoughts, even when they do not reflect her best self or betray a bit of condescension: “I think that farmers should be psychoanalyzed, and rethink their connections with the earth and masculinity. And not just farmers. All of earth’s foster children need to learn to foster her.” Readers may find these brash, over-the-top proclamations to be grating at first. But sympathetic readers will come to understand that Land of Love and Ruins is Eir’s open love letter to the complicated paths of her own mind. Her messy, uncomfortable thoughts are laid bare as a catalog of her mental process, preserved on the page and boldly open to the world.

The most satisfying sections in the book are the many brilliant reflections that feel surprisingly true: “All homes are, in some sense, museums. People surround themselves with things that remind them of the lives they once longed to live.” Moments like this are what keep readers turning the page to the very end of Eir’s journey and book. If you enjoy witty observation told through an intelligent lens of imagistic, wandering prose, pick up Land of Love and Ruins.

+++

+

+