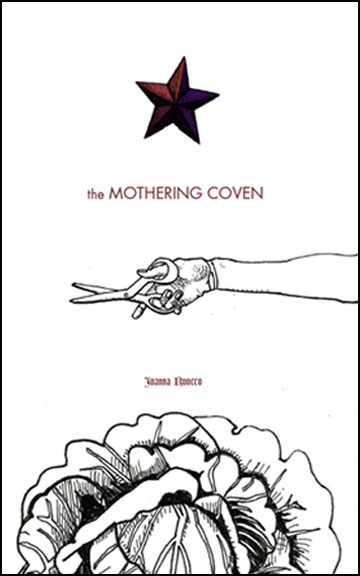

Ellipsis Press, 2009

Happy New Year and welcome to Necessary Fiction’s first book review. I’d like to quickly say hello and mention how delighted I am to begin work here as reviews editor. I’d also like to explain why I selected Joanna Ruocco’s novel The Mothering Coven for our first review.

First and foremost, it is an excellent book. However, I also wanted to mention that The Mothering Coven was published in the fall of 2009, a date that in the traditional world of reviewing might have disqualified it from garnering a “new” review. However, as we begin reviews here at Necessary Fiction, I wanted to highlight the fact that while many books at the larger, traditional publishers can get pushed aside as soon as a new season rolls around and another armful of books hits the bookshelves, this isn’t the case for most independent publishers. For Ellipsis Press, for example, which has quite a small publishing program, a book like The Mothering Coven remains an important part of its catalog and deserves repeated and sustained discussion.

So without further ado, let’s get that conversation started…

+

The title of Joanna Ruocco’s novel is an immediate clue to its atmosphere: a coven, a gathering of witches, ritual and incantation, celebration and mystery. This suggestion of unity and ceremony is indeed a motif which winds its way through the narrative of The Mothering Coven, a book about eight women living together, yet Ruocco is more interested in describing the breaks in the circle and the individual eccentricities which nudge this otherwise harmonious group to discord.

Mrs. Borage, the “mother” of this troupe of women, is about to turn one hundred. A party is in order. As the women begin preparations, Mrs. Borage builds eight cairns across the front lawn in front of their ramshackle house, cairns of leaves and stone and vines and cabbage heads. Eight cairns for eight women, although this number only serves to remind them all that one woman, Bertrand, has gone away.

Bertrand’s absence is just one of the unsettling situations which have developed inside the collective. There is also the question of Hildegard, the foreign student who seems to have fallen into a deep sleep in her closet-room under the stairs. And Ozark who is failing to complete her episteme. And Agnes who must take on more and more responsibility for the house. Not to mention an eviction notice which no one is paying any attention to as well as neighbor Mr. Henderson’s melancholy.

He regards the compost heaps, towers of harvest vegetables, rotting. He has a feeling that death is near.

Mr. Henderson thinks about death a great deal, alone in his garage, spinning and spinning his bowls until they’re so thin he can see his hands through the walls, like the bowls are made of glass. He pulls the walls up, higher and higher, narrow shafts that hold for an instant, tall and translucent — glass reeds, glass flutes — before collapsing again, into mud.

There is quite a lot going on in The Mothering Coven: party preparations, art installations, visits from Ms. Kidney and her sled dogs, trips into town, shamanistic journeys, paleozoological studies and a score of research projects. Often, the tone of these activities is deceptively lighthearted. But this is not a book to read with blithe inattention, as much of what happens and what is said could be perceived as nonsensical whimsy. A slower, more careful read detects the fragile threads of what makes this a novel and not a playful and poetic montage. The novel radiates a gentle humor yet the women are worried, sad, agitated. Their concerns are heartfelt. Where is Bertrand and why doesn’t she come home? When will the guests arrive for Mrs. Borage’s party? Why are things going wrong?

Despite the playfulness of the language and the sometimes comical, offbeat conversations, real moments of tenderness leap up from within these small scenes. For example, when Ms. Kidney arrives a few days before Mrs. Borage’s party, she inquires immediately about Bertrand. The reaction is immediate and communal:

“Shhhhh,” says Bryce and we all expel a little breath. Shhhhhh.

“Ah,” says Ms. Kidney, who lives alone at the tip of the narrowing North and has lost everyone, her three sisters beneath the green ice, marked by their upright sleds, for as long as we’ve known her.

The women and their eccentric preoccupations create a bizarre but beautiful little world. One of the novel’s pleasant surprises is that as the reader becomes familiar with Ruocco’s quirky landscape, it suddenly becomes obvious that, contrary to what one might expect, the coven is not meant to be different from the rest of the community. In fact, everyone the novel introduces is just as unusual and extraordinary as the women. By creating a seamless imaginary in this way, Ruocco subtly negates the idea of the women living in conflict with society as the novel’s central concern, and resettles its focus on their individual and refreshingly ordinary anxieties.

The action has moved to the kitchen. It must be time for lunch. For Agnes, it is a working lunch. She is researching vermilions, the tiny lions crushed by the thousand to color the crimson velvets of Versailles. Her heart isn’t in it. Vermilions had many hearts. Of course, they have been crushed to extinction.

The Mothering Coven is a slim novel and as soon as Ruocco’s world begins to feel familiar, it also begins to implode. As the party approaches, as the guests begin to arrive and minor catastrophes confront the women, suddenly one missing woman becomes two. The collective is unraveling! Ruocco finishes her unconventional novel with a pleasing combination of the spectacular and the sincere.