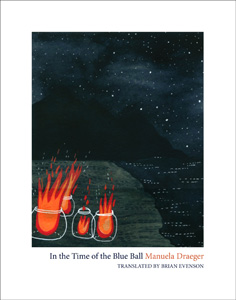

Dorothy, 2011

At first I thought it was a celestial accident that Publisher’s Weekly reviewed Manuela Draeger’s In The Time of the Blue Ball as a children’s book, recommended for readers 12 & up. Because I take perverse pride in being, at least when I initially approach a text, an old-school New Critical gal, I didn’t know Manuela Draeger was a pseudonym for Antoine Volodine, which is a pseudonym for yet another, unnamed author. And I didn’t know these stories were part of a ten-volume collection; each published individually, in French, as a series for young adults.

We learn in Danielle Dutton’s Publisher’s Note that this collection is part of a larger project, a “post-exotic,” where, among other things, the author writes “in French as if it were a foreign language.” It’s this particular objective that helps us understand the strangeness of these stories as more than strangeness, as more than just a series of charming or dream-like incidents. Because each sentence is energized by a bewildered, Aristotelian-like discovery. And as each sentence and story follows the next, a kind of entropy of language develops.

“The man who invented fire was a woman, actually. He invented fire and he tamed it. He was a woman named Lili…” Our narrator, a thwarted investigator of bizarre cases named Bobby Potemkine, tells us in the first story that this invention of fire happened much earlier, when time was not yet measured in months or hours. And though, “in those days people didn’t live with their eyes glued to their calendars,” their system of measurement, “red and russet moons…orbs, bubbles and balls” make distant and visual, yet strangely familiar, the concept of time.

Regardless, our narrator must find this inventor of fire, and fire itself, both of which have disappeared. Before we come to the quietly desolate conclusion (Lili hasn’t disappeared, she just lives in a different apartment), we meet Potemkine’s dog-partner, Djinn, another Lili who claims that she invented fire, a fly orchestra, mean-girl battes all named Lili, and a woolly crab, Big Katz, who runs an unsuccessful convenience store stocked with marshmallows.

Certain intra-story repetitions make more sense when we think of the stories as individual books. In “North of the Wolverines,” where Potemkine and the crab try to save a noodle named Auguste Diodon from his Promethean destiny of perpetually being eaten by children for dinner, Potemkine re-introduces Djinn and the first mystery of fire, though the narrator presents these facts through the filter of distrustful memory: “… if I remember correctly,” he says in a dependent clause aside. The form of the Dorothy Project book, the stories following one another in a single collection, makes a different meaning of these repetitions, of Potemkine’s unsure memory. These repetitions, and the narrator’s direct addresses to the reader, seem a way of trying to keep the reader near.

One of the most fascinating aspects of these stories is their place in a no-specific time. Is the fact that there’s no longer fire a sign that this is a post-apocalyptic world, so far into the future you can have a box “that makes cat or dog noises upon request”? In what era do the streets need to be swept of “shards of meteorites and cigarette butts”? The setting for these stories does seem to be, as Shelley Jackson writes in the blurb, the “frontiers of the imagination”: there are former wolverine factories, jellyfish that float through the air, tigers that talk and reek of pee. It’s fitting that an exquisitely imaginary world was created ex-nihilo. In the final story, “Our Baby Pelicans,” there are phone booths that can’t be used because no one has invented coins, and we learn that the apathetic, motherless baby pelicans who litter the streets aren’t hatched. “They come from an egg which hasn’t been laid by anyone,” so they just have to “wait until someone wants to lay them.”

But in the investigation to find the mother pelicans, Bobby Potemkine isn’t so hapless after all. He does find a mother for the babies: a giantess, a creature called a polar ratinette, who spreads out over the sea and land, who can’t move except to undulate, to ripple, “to the horizon, like a caterpillar without borders, completely flat, having fun getting nowhere.”

There are no epiphanic last moments in these stories, no happily ever afters. Dutton explains that Manuela Draeger:

…is not simply a pseudonym, but a character in one of Volodine’s other books: a librarian in a post-apocalyptic prison camp who invents stories to tell to the children in the camp.

Knowing this adds a poignant layer to each story. They all end with Bobby heading home alone, into a loneliness exacerbated by adventures sparkling with the company of gossiping battes and a crab who creates a protest no one joins, and a tiger named Gershwin who will attack anything that moves quickly in front of him, because “When someone starts running in front of me, it’s too late for distinctions between species,” and an unresponsive baby pelican he carried tied around his neck.

**I interviewed Yelena Bryksenkova, who designs book covers for the Dorothy Project, while I was Writer-in-Residence at Necessary Fiction. She mentioned that she had done a series of illustrations for In the Time of the Blue Ball, which you should check out, along with her interview, here.

+++

+

+

+