Our Research Notes series invites authors to describe their research for a recent book, with “research” defined as broadly as they like. This week, Cari Luna writes about her novel The Revolution of Every Day, out now from Tin House Books.

+

My debut novel, The Revolution of Every Day, is set in New York’s Lower East Side in the mid-nineties, in a community of squatted buildings. It’s inspired by the history of the Lower East Side squats, using actual events as the jumping-off point for a fictional story.

My debut novel, The Revolution of Every Day, is set in New York’s Lower East Side in the mid-nineties, in a community of squatted buildings. It’s inspired by the history of the Lower East Side squats, using actual events as the jumping-off point for a fictional story.

I was never a squatter. Though I lived only a few blocks away from the squats at the time, in a rent-stabilized studio, I had only the barest understanding of what was going on in those formerly abandoned tenements. The squatters seemed to exist in a separate, shadow city. And so I came to this book with empathy, but no real authority to tell the story. I had only my good intentions and my curiosity and my love of research.

Luckily, the events I wanted to explore happened as the Internet was becoming more widely used, so I was able to dig up squat-related list serv posts from the time. I also found some newspaper articles, and a small selection of related books. A few books were particularly helpful: Resistance: a radical political and social history of the Lower East Side, edited by Clayton Patterson; Glass House, by Margaret Morton; and War in the Neighborhood by Seth Tobocman.

What I very deliberately did not do was seek out anyone who had been involved with the actual events I was researching. This wasn’t born of laziness, but rather the desire to be sure I could write the novel that I wanted to write, unencumbered by anyone else’s idea of what should be told and how. I was concerned that if I interviewed people who had squatted in the Lower East Side in the eighties and nineties, I would feel beholden to tell their version of the story, to “get it right,” and in doing so miss out on the opportunity to uncover more universal truths.

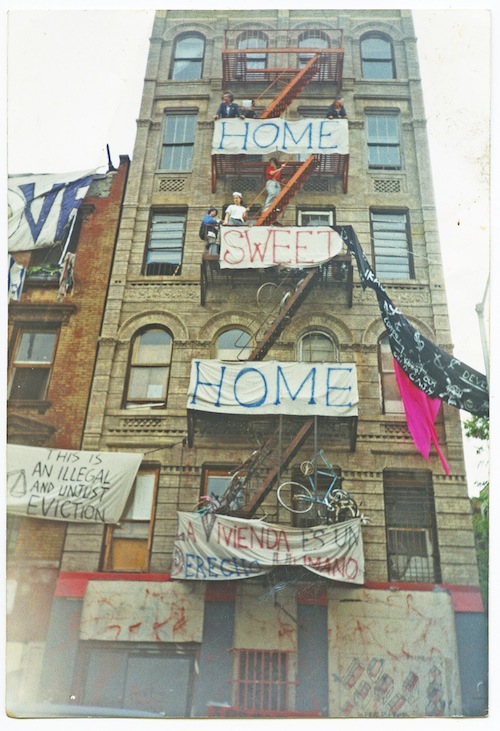

Photo by Sebastian Schroder (via EV Grieve)

I sound really confident in that approach, don’t I? I wasn’t so sure at the time, so I sought the advice of my friend Susan Choi, who had already written two novels based in recent history.

She told me, “Tempting as it is put your fears about inauthenticity to rest by having a ‘real life’ person from that situation vet the book, personally I would not think it was worth it. In my opinion the crucial thing is not the facts but emotional authenticity, and you can achieve that on your own. You’ll always wonder what juicy tidbit you might have gleaned had you gained the confidence of a participant, but as I say, the down side is too considerable.”

Inauthenticity was a real fear as I wrote The Revolution of Every Day. I was acutely aware that I was writing fiction based on recent events, which involved people who were still very much alive and kicking. All through the writing I was waiting for the day when the book would come out and someone would stand up and say, “Who the hell are you to tell this story?”

The only answer to that, of course, is, “I’m a writer. If you don’t like the way I’ve told the story, you’re free to write it as you see fit.”

And yet, true as that is, it’s also a bit too glib, isn’t it? When dealing with recent history, in particular, an author needs to remember that history is comprised of the personal stories of the people who lived it. I tried to be mindful of the fact that I was writing about events that were surely pivotal moments in some people’s lives. I did my best to treat the material with the utmost respect and diligence. But that still had to be balanced with the demands of fiction.

Photo by Peter Spagnuolo

The accumulated research on the squats led to my taking on the volunteer role of social media director when the Museum of Reclaimed Urban Space (MoRUS) opened in December 2012 in C-Squat, one of the last remaining squats on the Lower East Side. This past spring, I had the opportunity to read from the novel at MoRUS with three former Lower East Side squatters whose names had come up frequently in my research: Fly, Frank Morales, and Peter Spagnuolo; people who had lived — and shaped — the history that inspired my work.

Fly, an artist and musician, had produced zines that brought me back to that time and place. Her interview in Resistance was key to my understanding of the community I was writing about.

Frank Morales, a housing-rights activist and Episcopal priest, squatted as a form of direct action. Interviews with him found online and in Resistance gave me an appreciation for squatting as radical political protest, which would have applied to my more politically motivated characters.

Peter Spagnuolo, a poet, was a squatter in one of the 13th Street squats at the heart of the book’s events. He led the legal battle for adverse possession, and when that failed and the big eviction came on May 30, 1995, he was welded into his apartment to await the siege, responding to the militaristic police action with passive resistance. An article published in the New York Times the day after that eviction — the very first thing I read as I began my research in the fall of 2005 — quoted him. He was asked about the squatter movement, and in response he said, “Is it really a movement? Or is it just a lot of motion?” That statement by Spagnuolo, simple as it perhaps seems out of context, was profound for me. It shaped my understanding of my entire project.

(Do please note that, as much as I admire Fly, Frank, and Peter, none of my characters are based at all on these real-life squatters or any others. The characters are wholly invented.)

And so there I was, emailing with these people who had had such a tremendous impact on my work, planning a reading together at the museum. I sent them each a copy of the book, worried about what they would think about a novel set in the squats, written by someone who hadn’t been a part of it. Each of them responded enthusiastically and supportively. After all that stress and angst on my part, Fly invited me over for tea; Frank thanked me for keeping their story alive; Peter thanked me for getting it right.

Someone, at some point, will surely question my right to tell this story, but I don’t worry about that anymore. Frank and Peter and Fly are cool with it. That’s enough for me.

But now that I know those three, and others who were there, thanks to my work with MoRUS, would I handle the research differently? I’ve learned so much more from them about those days in the squats since completing the book, day-in-the-life stories and the type of “juicy” details Susan Choi had spoken of. Even so, I’m glad I didn’t meet them while I was still writing it. They are compelling, charismatic, fiercely intelligent people. I would have been absolutely paralyzed by the desire to “get it right” for them, to the point that I would have either ended up with a stunted, confused book, or no finished book at all.

+++