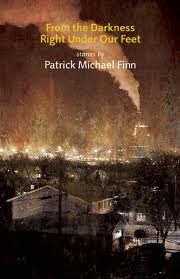

Black Lawrence Press, 2011

The eight stories in Patrick Michael Finn’s collection, From the Darkness Right Under Our Feet, are so thematically and stylistically cohesive they create a story collection that reads very much like a novel. These are not linked stories, not in the traditional sense; they do not share characters or even strict time periods. But they do share Finn’s rigorously consistent narrative style, his delight in intense sensory description and a firm geographic anchor in the city of Joliet, Illinois.

Together, these miniature novels create an unsettling fictional world of mid-western America, a detailed and vivid narrative rendering of the outcome of the area’s immigrant, industrial and social history. Finn’s Joliet is not a pretty place—it is impoverished, bigoted and polluted, not to mention rife with all of the human frustrations and drama that are necessarily found when those painful adjectives become a city’s reality.

Here is Joliet, seen through the eyes of “Shitty Sheila’s” own Sheila, the city’s possibly most objective viewer as she is the only character who came to Joliet as an adult:

And when she went outside to try to breathe the meanness out she saw dirty yellow lights dimly spotting cracked and buckled sidewalks and lifeless streets that all stank like machine oil. An empty junkyard waiting for hulks of crushed and wasted steel to fall in great stacks from the darkness.

Aside from geography, From the Darkness Right Under Our Feet is also unified through its assortment of protagonists. Although not exclusively, Finn does tend to focus on the pubescent male. Five of the eight stories feature a variation of the kind of young man who might have grown up in Finn’s Joliet. These young men are angry, lustful, dangerous and confused adolescents, or simply put-down and defeated, and often a combination of all of the above. They suffer injustices and more often outright abuse. They inflict the same in varying degrees on anyone further down the food chain, or higher up if they can get away with it. Finn is definitely mining a certain psychological territory in this collection, a space where anger and shame find release in violence. His young men negotiate the depth and severity of that violence, crossing over a certain line and retreating backward, with varying degrees of success.

In the collection’s titular story, the young protagonist is fighting against his parents’ unwillingness to believe there are rats in the family home. But the fight is larger than that—it’s about what having fat, clumsy, greedy sewer rats hiding in the house means about the house and its inhabitants, about feeling ashamed of one’s home, one’s family. This narrator only barely crosses the line I mentioned above but others will go much further as their pent-up rage finds no other way of satisfying itself.

Like the narrator of “Between Pissworth and Papich,” who will ultimately take his anger further than any other character in the collection. Although his story is one of the more difficult to read, eliciting a mixture of horrified fascination and intense pity, it also includes a tiny moment that best documents the psychological element linking Finn’s assortment of broken and battered young men—a self-disgust turned outward. After being humiliated by his father in front of his siblings, the narrator of “Between Pissworth and Papich” retreats into a moment of solitude to give vent to the powerlessness he feels:

I stayed in the bathroom. I shut the door, spat on the mirror, then rubbed the spit with my fingers before I smeared most of it off with a towel.

“Fuck you,” I whispered to my reflection. Who I pretended was some lesser prick about to get his ass knocked into next year. “Go fuck yourself where you eat, motherfucker.”

Aside from this carnival of young men, Finn imagines the lives of two very different women and their experiences in his vision of Joliet. In “Shitty Sheila” he gives us a woman who was supposed to find herself living a wild, fun life with girlfriends in Chicago but gets stuck working as an exotic dancer in Joliet. A woman with limited life skills and limited choices, someone whose vision of herself has so deteriorated that she spends most of her time blacked out on cheap wine. Sheila’s existence is precarious and Finn, to his credit, reveals exactly how precarious with an ending that is both a surprise and a confirmation of the hard reality of Sheila’s entire life.

Although worlds apart from Sheila, Helen Dzurko, in the collection’s quietest story, “In What She has Done and What She has Failed to Do,” is asked to confront a similar set of challenges: widowed, mistreated by the people who are supposed to be her friends, unskilled, alone. On the surface this is a story about faith, as a group of children have discovered an image of the Virgin Mary in the upstairs window of a vacant home on Helen’s street. But that outward story is subtly mirrored in Helen’s struggle to find faith in herself and her own actions.

Only two of the stories in this collection give their main characters what, in comparison to the others, could be called a happy ending. I don’t mean to suggest that the point of a short story is to have one or the other, but the difference in endings in From the Darkness Right Under Our Feet is interesting because, the two (arguably three) times it happens, the movement from desperation to possible salvation rests on the slimmest of artifacts: kindness. In Helen Dzurko’s case she is one of the only protagonists to have the memory of real, shared kindness, steadfast love even, to hold her up when times are difficult:

Whenever Frank got too weak to face the day, when he couldn’t get out of bed because he’d lost both his boys, Helen would sit with him and say things like, “Now Frank, you know that laying there in bed all day’s just going to make you feel worse. And you know it won’t change anything. We need groceries, so let’s go and get out of the house for a while. Come on, up, up, up,” until living seemed possible even in its worst punishment, when it takes your children away. And when Helen had her bad days (and she knew they surely outnumbered Frank’s), when she’d stay up all night in the kitchen and smoke, Frank would hold her hand and tell her, “You’ve got to remember that there’s still beauty in the world. You’ve got to remember.”

For the collection’s most abused young man, Louis, in “For the Sake of His Sorrowful Passion,” salvation comes almost out of nowhere, and although its long-term success is uncertain, Louis’ moment of deliverance hinges on the tiniest spark of kindness. After the ugliness that was his life, this wholly unexpected shift in paradigm fills the reader with a profound sense of grace.

This review focuses more on the meaning of the stories in Finn’s collection than on the writing; this is simply a choice and not a comment. Narrative style is a strong element of Finn’s project, as he works to convey the violence of his characters’ lives and their inner and outer responses to that difficult reality. He maintains tremendous control over the movement of each story, and he has a way of stacking images that complements the emotional claustrophobia of many of his characters. Viewed from any angle, From the Darkness Right Under Our Feet is a powerful collection and as I finished the last piece, I thought only of wanting to read more of Finn’s work.

+++

+