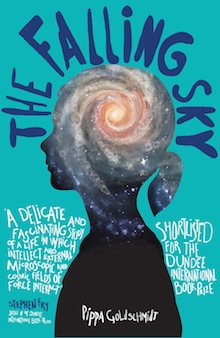

Our Research Notes series invites authors to describe their research for a recent book, with “research” defined as broadly as they like. This week, Pippa Goldschmidt writes about The Falling Sky (Freight Books).

+

Doing a PhD in astronomy was research for writing my novel, although I didn’t know it at the time. I was a PhD student at the Royal Observatory in Edinburgh, a fantastic Victorian gothic pile and one of the largest centres for astronomy in the UK, where I spent nearly four years constructing a quasar survey (a quasar is a peculiar sort of galaxy with a supermassive black hole in the middle). For this, I had to build databases of objects scanned from photographic plates, calibrate the data and then spend time at a telescope measuring the quasars’ redshifts. Finally I did some statistical tests to show that there are a larger number of luminous quasars than was previously thought. All very interesting, if you’re interested in quasars. Which I was, at the time. I spent a good chunk of my waking hours thinking about them and wondering how they formed in the first place and how long they lasted.

Doing a PhD in astronomy was research for writing my novel, although I didn’t know it at the time. I was a PhD student at the Royal Observatory in Edinburgh, a fantastic Victorian gothic pile and one of the largest centres for astronomy in the UK, where I spent nearly four years constructing a quasar survey (a quasar is a peculiar sort of galaxy with a supermassive black hole in the middle). For this, I had to build databases of objects scanned from photographic plates, calibrate the data and then spend time at a telescope measuring the quasars’ redshifts. Finally I did some statistical tests to show that there are a larger number of luminous quasars than was previously thought. All very interesting, if you’re interested in quasars. Which I was, at the time. I spent a good chunk of my waking hours thinking about them and wondering how they formed in the first place and how long they lasted.

But because telescopes tend to be built on tops of mountains, I spent a fair amount of time in some seriously remote places, such as the Andean desert in Chile and the Blue Mountains in Australia. The observatory in Chile is so remote and so high up that there’s no wildlife, no birds, nothing but rocks and desert. Working there, I had a lot of time to think. As well as thinking about quasars, I thought about how amazing the night sky looked (qualitatively different to any sky seen from urban sites because the sky in these places is just chock full of stars), but also how lonely and bored I was a lot of the time, and how far away I was from anything I could call ‘home’. It felt like living on the Moon.

But when I wrote my thesis and some scientific papers, of course none of those thoughts were included. They weren’t relevant to the science. Or were they? I started to ponder the gaps in the scientific literature. Who decides what is and isn’t relevant to the experiment being written up? If you’re a PhD student learning how to write scientific papers, you’re taught by example, by reading other papers, and by having your own efforts laughed at by your thesis supervisor. You very quickly learn to make it all as objective and authoritative as possible. For example a lot of scientific writing uses the passive voice to remove any hint of the humans behind the science.

I felt like I wanted to add in those humans, but I didn’t know how. It was only several years later, after my PhD and towards the end of my last post-doc fellowship at Imperial College when I decided to leave academia that I started writing fiction, and I realised I could now say what I liked about doing science, and fiction would be an ideal way of exploring all those uncertain, subjective nebulous feelings. So I started writing about Jeanette, a young astronomer trying to make her way in academia.

To trigger this exploration I had to give Jeanette an obstacle to overcome, and at first this obstacle seems more like a gift. So, in the book, she makes a discovery that seems to contradict the standard Big Bang theory. Initially this helps her career, but eventually she realises that by challenging this theory she has actually undermined her own sense of order in the Universe. That, combined with a childhood tragedy that resurfaces, brings her to the edge of sanity.

I thought long and hard about the precise form of Jeanette’s scientific discovery. In reality there have been several challenges to the Big Bang theory, and I wanted one that was easy to get across to the lay reader without needing too much physics to explain the significance. The theory predicts a one-to-one relationship between a galaxy’s redshift and its distance; the larger the redshift (which is what you measure at the telescope) the further away the object is. And in the book this relationship is challenged when Jeanette and her colleague find an apparent physical link between galaxies at different redshifts.

I hoped to build a visual picture in readers’ minds of these galaxies the way that Jeanette and others might see them on the computer screen, two blobs with a string of ‘something’ between them. And as Jeanette struggles with connecting and communicating with other people in her life, and has done since her difficult childhood it seemed to me to be an inevitable metaphor for her isolation. Perhaps that’s why she’s so keen to ‘see’ this connection. It may console her for the lack of connections around her.

And that’s the other part of the research. Being human and being (self)conscious. When I started writing the story of Jeanette and how she blunders her way through her work and her life, I realised that I was going to have to think harder than I had ever done before about exactly how people react to childhood trauma and to their own mistakes and inadequacies. In short, I was going to have to become an amateur psychologist. I’ve never been particularly interested in psychology, probably because I’m a typical physics snob who finds it difficult to think of any other science as worthy of the name (although I have a grudging respect for biology) but I sweated over my characters, and did my best to make them believable and fully rounded. In doing so, I realised that perhaps I’m not interested in the academic discipline of psychology because for me fiction fulfils that need, it tells me what I need to know about people. Although fiction is made-up, it has to mimic real life in order to work, and I think it actually goes further than that, I think we can learn about real life by reading fiction. It’s a kind of thought experiment.

Anyway, here are a few books that I found useful when writing my novel:

- The Elegant Universe- and _The Fabric of the Cosmos, both by Brian Greene

- The Sleepwalkers by Arthur Koestler

- The First Three Minutes by Steven Weinberg

- The Cosmic Frontiers of General Relativity by William J. Kaufmann

+++