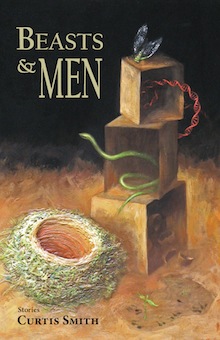

Our Research Notes series invites authors to describe their research for a recent book, with “research” defined as broadly as they like. This week, Curtis Smith writes about Beasts & Men, out now from Press 53.

+

I trend toward the packrat-ish. It’s one of my more benign character flaws. I assign inflated emotional values to rather mundane objects. I opt not to throw out a knickknack that has been doing nothing more than collecting dust for years, my mind reeling with images of its future use. Unfortunately, my house is old and small, lacking the proper storage capacity for a man who holds onto his past. Boxes pile up, the basement reduced to narrow passageways. I ignore the mess until some sort of critical mass is achieved — and then I’ll clean, a haphazard, anxious, and often chaotic purging.

I trend toward the packrat-ish. It’s one of my more benign character flaws. I assign inflated emotional values to rather mundane objects. I opt not to throw out a knickknack that has been doing nothing more than collecting dust for years, my mind reeling with images of its future use. Unfortunately, my house is old and small, lacking the proper storage capacity for a man who holds onto his past. Boxes pile up, the basement reduced to narrow passageways. I ignore the mess until some sort of critical mass is achieved — and then I’ll clean, a haphazard, anxious, and often chaotic purging.

I was in such a state when I came across three cardboard boxes containing old notebooks. I’d started writing in my late twenties, and now, on the cusp of 50, I reconsidered scraps written ten, fifteen, twenty years ago. Much of what I read was cringe-worthy, the stumblings of a writer just beginning the search for his voice. Instead of simply chucking the boxes, I yielded to my inner packrat and embarked on a project. I bought a new notebook, and at the top of each page, I jotted down an image or sentence I’d discovered in these old journals. All told, I probably had close to a hundred such entries, and on each page, I attempted to fashion these salvaged images into flash pieces. Over the course of the next year, I worked on those pieces, all the while reading the flash work of many writers I admire. In all, I published thirty-some stories that shared this common origin, and twenty-six of those pieces are included (along with four long stories) in Beasts & Men, my new collection from Press 53.

I mention this process because it reminded me of how research used to be in the pre-internet times — the combing of card catalogues, the scouring the university’s book shelves, the checking out of a book that hadn’t been opened in years (that smell!), the viewing of microfilm on eye-straining screens. The process had the feeling of a hunt, an actual physical ferreting out of information. Writing this book felt similar in that sense, the rescuing of materials from a space forgotten, one slightly musty and dank.

Much of the research for the stories themselves came in terms of questioning my own memory. I’d dwell on an image, trying to recall it in terms both physical and emotional. Not an easy task sometimes — especially considering how often my day-to-day memory fails me. One of the stories involved the use of an 8mm projector. No doubt twenty-plus years had passed since I’d operated one, but since the projector was so vital to the story, I needed to heighten its presence. So I sat and imagined it for a while, thinking and thinking until I heard the clatter of sprockets. Until I saw the stammer of its loop. Until I could almost reach out and touch the dust motes filtering through the casing’s shafts of light.

At first, I assumed I hadn’t done much hard, fact-collecting research for this book, but as I paged back through it, my thoughts changed, and I divided the stories into two types — ones where research played a major role, and another in which its role was relatively minor. The minor ones had a sentence or two that contained facts that needed to be verified. A sentence doesn’t amount to much in a story, but when one considers reading as a type of dream, a state easily ruined by a wrong note, then the importance of getting things right becomes apparent. What did I research? Here’s a partial list:

- types of antipsychotic drugs

- Ashman’s Phenomena (a type of tachycardia)

- Fish found in the Great Lakes and in the rivers of the northeast (and the bait used to catch them)

- Details of the Manson murders

- The breeding of hunting dogs

- The blooming cycles of common flowers

- World War I rifles

- The difference between possum and opossum

- The procedure for a school tornado drill

Then there were the stories which required a greater degree of research. One story centered on elements of physics. I am kind of a geek for science; still, I needed to double check my facts — the hiss of close-piped resonators, the calculation of the coefficient of friction, the difference between real and virtual images, the relationship between hertz and dissonance. Another story dealt with Lenin’s corpse — and once I learned the body required regular injections and bathings, I knew the mortician was a character too good to leave out (research leading to a new character/voice in the story — that was pretty cool).

The collection’s final story concerned a sight-seeing safari. Again, there was a fair amount of Googling — getting the proper names of flora and fauna, reading others’ descriptions of the region. But to get a better feel for the situations, I found myself returning again and again to YouTube. I watched the maw of traffic in Nairobi. I watched rugged vehicles trundle down dirt roads, the savannah stretching to the horizon in all directions. I watched migrating herds stretch like giant shadows over the landscape. It occurred to me what a wonderful age we live in, where the visual is available to us with a click, a second-hand reality delivered into the comfort of my home.

So there you have it. Research, yes. Yes, please.

+++