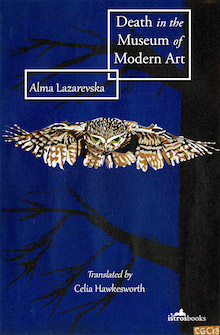

Istros Books, 2014

The Siege of Sarajevo forms the backdrop for this collection of six stories by Alma Lazarevska. Written during the events described in the book and published in 1996, there is no danger of this first English translation feeling out of date. We need no geographical or historical details to grasp the timeless quality of these tales. This is a description of any besieged city, of life being put on hold, of endless purgatory.

There are no full-blown descriptions of wartime horrors in these pages: only occasional oblique references to snipers and balls of fire falling on the city. Instead, we are introduced to a couple (referred to as Him and Her) and their son (the Boy). The first-person female narrator present in nearly all of these stories simply describes domestic scenes, mild gender skirmishes, food shortages, the claustrophobia of being unable to leave one’s own home. These closely observed details pile on, page after page, until the personal becomes political, a form of resistance, a quiet heroism that is very moving to witness.

Although the overall impression is one of yearning for the past and uncertainty for the future, each story has a slightly different feel. The opening story, for example, is the only one written in the third person and tells of the unfortunate Dafna Pehfogl (a nickname derived from the German Pechvogel — unlucky). It has a ferocious black humour to counteract the sadness. Dafna’s entire life is blighted by her clumsiness, bad luck and unfortunate coincidences — perhaps also by her label within the family. The family is proud of their Imperial past, of their long and resonant surname ‘that took two intakes of breath to pronounce’, the clink of ‘china with the gold trademark Alt Wien’ and Dafna is not quite up to standards. Yet none of her suitors are deemed quite good enough for her either, so she quietly and inexorably slips into lonely spinsterhood. When the city is partitioned, the only one of the family left on ‘this side’ is Dafna. The family arranges for a guide to smuggle her out of the city, but as she crosses ‘the deserted bridge between here and there’, the soldiers spot her and she becomes the victim of a terrible (and scurrilous) misunderstanding. She falls ‘like a large strange bird hit by a stray bullet with no hunter to claim it.’ In that instant, she becomes the albatross of the Ancient Mariner, taking all of the sins and failures, mistakes and misfortunes of her family upon her. There is a collective shudder of realization that there is no one left to burden with one’s unhappiness, that from now on each one is responsible for their own fortune.

The remaining stories have a less clear story arc: they feel more like still life portraits of a city under siege. The narrator’s mind seems to flit from one random fact to the next, yet the smallest gestures become significant. A petty quibble over wasting matchsticks becomes a desire and belief that the couple can save lives and somehow influence matters (‘How We Killed the Sailor’). Suitcases once used for travel are now limited to the hurried trip to the cellar, while postcards depicting lurid sunsets from the Adriatic become a symbol of all that is lost (‘Greetings from the Besieged City’). Dry throats and fear of choking lead to endless thirst for milk and water (both not easily obtainable in the city), which become a metaphorical thirst for freedom of movement and ideas (‘Thirst in Number Nine’).

Amidst all the domestic details, there are some light surreal touches: the dwarf architect insisting on north-facing bedrooms in ‘The Secret of Kaspar Hauser’ or the magnified blue eye of the Russian neighbour peering silently through the peephole in ‘Thirst in Number Nine’. Unsure of the duration of their ordeal, uncertain about their ultimate fate, the inhabitants of the city are succumbing to collective hallucinations, like the sailors dying of thirst in windless oceans in the Rhyme of the Ancient Mariner.

In an attempt to preserve normality in a world gone mad, the narrator tries to protect her son by changing the ending in a book she is reading out loud to him, so that the main character does not die (‘Greetings from a Besieged City’). She remembers a classmate, Otilija, who had always wanted to improve upon literature and reality. ‘If I were a writer every book would have a happy ending.’ Otilija’s own story has an ambivalent ending, as she departs into madness ‘just in time’, before the ring of death tightens around the city and before ‘little heaps of children’s flesh’ could tear through her heart and mind.

Ultimately, the mother in the story realizes that she cannot defend her family against sadness and loss, that reality will always seep through the layers of protection she tries to maintain. The most unbearable story is not the one with the sad ending, but the one with no ending at all, only the pain of endless uncertainty.

If only I knew what a happy end was! Did I know once and have forgotten? Like Anna Karenina whom Tolstoy finally allowed not to jump under a train. And now she is standing on the platform… standing, standing, standing… and what next?

The title story closing this collection is especially poignant. It describes a project organized by the Museum of Modern Art in New York, based on questionnaires sent to one hundred inhabitants of Sarajevo during the siege. The author quietly exposes the wicked irony of these opinion surveys: asking, among other things, what they fear, where they would like to live and how they would like to die, as if any choices were open to them. After much deliberation, the narrator answers that she would like to die ‘in her sleep’, only to discover that her partner, who was urging her to reply to this question, had answered ‘I don’t know’. Thereafter, she finds herself struggling to fall asleep, imagining herself and her fellow Bosnians exhibited in a glass case at the museum, to be examined and misunderstood by the rest of the world.

The city is still besieged. The nights are often long and empty. Then I suffer from insomnia and the bags under my eyes are deep. He tells me that he thinks I elude sleep and not that sleep eludes me.

Lazarevska’s deceptively simple and spare style is perfectly suited to the un-showy, non-indignant gradual reveal of horrors. The translation by Celia Hawkesworth closely captures the delicate nuances of the original: nearly every sentence is imbued with double meaning, so much is left unsaid. There is a poetic silence between sentences, between trains of thought, mimicking perhaps the silence after mortar attacks. The stories will reward close reading or, better still, close re-reading. Death may be the first word in its title, but the book is really about the triumph of life.

+++

+

+