Featherproof Books, 2010

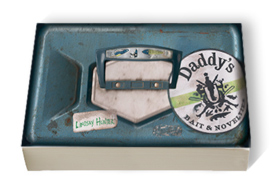

An animal in the road that’s been run-over or someone passed out on the sidewalk in broad daylight—there are things that most people can’t help but stare at as they pass. And then there are the less blatant temptations: the curtain half pulled back on the bedroom window of that one house on the block; the gaping handbag of the lady at the bus stop who always carries a plastic baby doll bundled up in her arms and sings to it like it was her own flesh child. These darker spaces draw your eye like a tractor beam; they call out for furtive investigation. What’s going on in there? they seem to say. Lindsay Hunter’s debut collection of shorts, Daddy’s, is just like that. It arrives looking like a beat up tackle box just begging to be opened. And once you start flipping the sideways pages, peering through the curtains and over the fences into Hunter’s world, it is powerfully hard to look away from the sting and gore and ache of what’s behind them.

In 24 tales of twisted and strained relationships, Hunter explores and beautifully corrupts the Southern Gothic short-short. From a family of competitive eaters, to a woman whose children never make it to age two—these people revel in extremes. Here is arson, murder, and a host of unmentionable crimes against nature. It is the severity in their lives that keep the residents of Daddy’s apart from one another, because these characters are all alone, some desperately, some furtively. They keep their thoughts to themselves, or when sharing, hide their motivations.

Later we’d tell about how bored we were and what a redneck Tina’s mama was. We wouldn’t mention how glamorous it felt to say we were bored, and how in the dark we got chill bumps up and down our arms at the idea that this was life, and life smelled like peach carpet spray and cinnamon chewing gum and cheap-flavored wine, all backwashed up. (from “Fifteen”)

Twin obsessions with food and sex swirl throughout these tight, concise gems. Each story drops the reader into the middle of deep secrets and terrible, inevitable acts. Hunter paints a backdrop of taboos sticky with something sweet, but in bites so small your fingers won’t even betray a trace of where you’ve been.

The desert is a good lesson in life. It proves that what you want most will most likely stay out of reach. That fire was mine, was my love, was the breath in my lungsacks. I heard the dogs behind me singing their brutal chorus, I knew they remembered what it was to beg, that fire moving fast toward the end of the earth. (from “Out There”)

While longer pieces like “The Fence”— which explores a woman’s attraction to an invisible fence as a response to her husband’s violent attraction to her—are slow, scarring burns, most of the pieces in Daddy’s are short, hitting the reader fast and hard. “Wolf River,” in around 300 words, tells a much longer story about lost love and the doldrums of responsibility between its careful lines. The most horrible acts in “Marie Noe Talks to You About Her Kids” are left entirely up to the readers’ imagination, while those in “Fifteen” are thrown out casually, the way one would deal a hand of 52-pickup.

There is no flowery sentiment here, and Hunter’s stories are far from formulaic. Some read as streams of consciousness from the minds of her characters, others as litanies. They are love stories, odes, and murder ballads. They are also creepy in the best possible sense: once you catch a glimpse, you won’t be able to look away.

+++

+