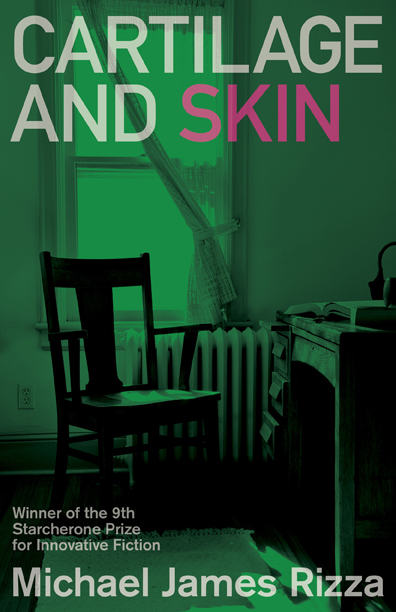

Starcherone Books, 2013

Michael James Rizza’s Cartilage and Skin is a novel about connection and the body. The connections may be real or imaginary, physical or emotional, mental or moral. External, like skin, or internal, like cartilage. The bodies in this narrative are desiring and imperfect. Fragile. They have the power to be hurt, and they have the power to hurt others.

The first-person narrator, Dr. Parker, is an academic, apparently on sabbatical to finish a book which he eventually abandons in favor of poetry. His attention swirls inward into his imagination and philosophy and, as Parker says himself, “going inward was always a descent.” This is the trajectory of the novel: inward, and downward, a literal and figurative spiral around Parker’s apartment while he dreams of isolation, relationships, and escape.

The narrator is consumed with self-loathing. He is completely self-aware, self-conscious, and self-absorbed, and he is disgusted by himself and what he believes others see in him, “a glistening knot of cartilage and skin” or “a grotesque absurdity, a lumbering monstrosity.” His constant self-surveillance and mental self-flagellation puts the reader in mind of Crime and Punishment or Notes from the Underground. His dramatic language and constant fantasizing reveal a tenuous connection between the self and the other and between fantasy and reality.

Parker is obsessed with relationships between people—the severing of old ties and the formation of new ones. He both longs for and fears connection with others, so he is always struggling for control. He purposely severs his professional relationship with Morris by standing him up at their meeting. Then, he does the same with Morris’s sister, manipulating her well-meaning, naïve nature. He responds to a stalker by stalking him in return. Many of his relationships are in fantasy only, a place over which he has complete control. He creates elaborate scenes involving his corpulent neighbor, her exhibitionist pen pal, and an artist he has probably never met. In all of these stories, save one, he is the center. He imagines romantic flings with the women and threatening obsession from the men. Some of his fantasies fall apart, while others become real, pleasant or frightening as they may be.

However, his most vivid, and troubling, fantasy is the one from which he is absent. In the first pages of the novel, Parker begins paying a destitute boy to run errands in order to irritate his landlord. The boy shows up at his apartment one night in bad shape, asking to use the bathroom. The boy collapses, the authorities are called, tests are run. The boy is horribly injured. The boy is covered in semen. Parker’s life is turned upside down during the investigation.

The wholeness of the narrative and the wholeness of the bodies in that narrative are tied together. After the investigation, which he only relates in barest summary, Parker continues his wandering, his feints at personal connection. But his body is disrupted when he slips and falls down the front steps of his building, believing his landlord has hit him in the head with a shovel. His body is disrupted, and it is this event that prompts him to consider the disruption of the boy’s body and to disrupt the structure of the novel as well, splitting it apart. Parker pieces together a story of the boy’s past that functions, literally and figuratively, as the center of the novel. He concocts an elaborate tale of bad luck and cruelty and pain that the reader cannot be sure is true, but Parker presents it as fact.

The boy’s story engulfs the structure of the novel, just as it engulfs the narrator’s life. The novel changes from a linear, continuous plot told in singular first person to a series of third-person shorts that require the reader to draw inferences and form assumptions.

The connective tissue of the narrative has been snipped apart, and it’s up to the reader to stitch the pieces back together to form a coherent whole. However, Parker tells the reader he has “filled its darkest places with my imagination,” but the imagined portions are impossible to detect, further blurring the distinction between fantasy and reality.

And then, with even less warning then the first shift, the novel resumes the linear continuous present, returning to the narrator and his landlord’s assurances that Parker only slipped, he was never struck. This constant questioning of the narrator’s perceptions and ability to separate fantasy and reality play to the core of this novel, raising the tension and dread around a man who, all told, does very little.

The interplay between fantasy and reality is further complicated by the narrator’s obsession with observation. He constantly relates and comments on the physical details of his body and the world around him, creating a verisimilitude to his point of view that further confuses the connections between fantasy and reality. Can the reader trust Parker’s observations, or is he simply filling in the dark places again? Some of the fantasies are or become real, and in many ways the movement of the novel is the joining of the darkness of reality and the darkness of Parker’s imagination into one. While Parker has a chance at something better, a real relationship, he cannot bring himself to risk reaching for a brighter fantasy that may still just slip away.

Ultimately, this is a novel about the struggle to know others and to know oneself in a world where bodies feel and inflict pain, where identity and relationships are composed of both fantasy and reality. This is a world where a pile of rags can become a human being, where Parker can change from a villain to a victim to a hero and back again. Cartilage and Skin is a novel of intrigue, both in content and structure. It is a neurotic noir.

Its final moments are horrific, not because of what the reader sees, but because of what the reader imagines. Parker, who has for so long filled in the dark places for us, leaves the final dark place for the reader to fill. He has taught us to imagine darkly. He has revealed the dark imagination already within us that makes it so hard to forge the connections for which he so desperately longs.

+++

+