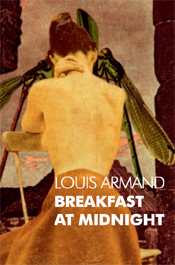

Equus Press, 2012

Prague. Cold rain on black leather jackets. City bridges looming over an icy river. Hard alcohol, cigarettes, cocaine, prostitutes, men who look like corpses, men who look at corpses. Decay both physical and psychological. Violence. Louis Armand’s Breakfast at Midnight is an unsettling read, even when held conceptually at a distance with the somehow-softening title of “modern noir.”

Despite this genre tag, Breakfast at Midnight is not a book to romanticize into some nostalgic noir category, even if at times it seems to be reaching for this itself. The novel contains allusions to various types of noir, scenes that echo the hardboiled detective novel and many wonderful cinematographic hat tips to film noir, all superbly carried off — the woman on the bridge in the rain, for example, an image we are given in several different ways, is one such echo:

But halfway across the bridge she was there again, leaning against a concrete railing with the city lights behind her. She was wearing a black coat — the same coat she’d worn the night we left the Ace of Spades. It drooped under the weight of the rain soaking it, slipping down. Her hair clung to bare pale shoulders.

Or this end-of-scene, done in a way that Armand favors, with a close-up of one element of the decaying city:

Inessa whispers something in my ear and slips away among the shadows. Footsteps lost in the gloom. A moment later the lights of the carousel flicker and come on. Cracked gilt mirrors and rusting candy-striped poles shine in the wet. Then the lions and unicorns and horses start going around. Accordion music at half-speed belches from a megaphone, sounding weirdly in the big empty night.

But besides these nods to an earlier style of noir, Breakfast at Midnight is a modern and violent neo-noir. Gritty and disturbing, it details some of the deepest darknesses of the human psyche. The novel shelters a decrepit world of humans, all of whom have only a tenuous grasp on some last shred of their humanity.

Overall, plot does not so much matter in this book — the mood, the style, the imagery and emotion are really at the heart of the work; also, Armand is experimenting with depression and psychosis, how to describe them, how they are experienced — but for the sake of review, here is a bare bones that will suffice: a young man in Prague relives a past relationship when the body of a young redheaded woman surfaces in the river and he goes with his friend (if that’s really the word to describe their connection), Blake, to photograph the body. Blake is a pornographer of women’s bodies, both dead and alive, although he seems to prefer them dead. Our narrator is a fugitive, having exchanged his life (via swapped passport in a South American jungle) for a dying man’s ten years before. The reason for his shadowy existence is slowly and circuitously revealed and has everything to do with the body of a young red headed woman. Not the corpse we meet in chapter two, but that body from his past, a powerful physical presence that hovers throughout the entire book.

I use that word “body” on purpose because what happens to the narrator of Breakfast at Midnight isn’t so much because of his relationship with a young woman named Regen, a childhood companion and teenage love who disappears some ten years before the book opens, but because of certain actions taken out on her body. We don’t really know what happens to her as a person; Armand doesn’t ever move far enough away from the confines of his narrator’s crumbling reality for us to do more than guess at Regen’s experiences as a person. While that tight focus on the narrator’s consciousness is one of the book’s great successes, it is also one of the reasons for the unease the book provokes. The novel’s past tense story contains two sides of a narrative: on the one side is a set of actors, including the narrator, and on the other, is this woman’s (inert, inactive) body. That isn’t a balanced equation, and no matter the streamlined quality of the book’s noir aesthetic, no matter the vivid layers of cinematographic scene, no matter the narrator’s self-revulsion, there is something very disconcerting about that imbalance, something that makes some of the violence in the novel appear to be for pleasure, for titillation.

The other aesthetic working throughout Breakfast at Midnight is a wonderfully executed nod to Kafka’s special brand of disorienting surrealism. The narrator’s Prague is a dark labyrinth of small streets, bridges, and bars, and as the present-tense part of the story gains momentum, and especially as the narrator succumbs to reliving his traumatic past, it becomes difficult to differentiate between what is dream/hallucination/alcoholic delusion and what is reality. That blend of delirium and truth is intricately tied up with the narrator’s revelation of his personal hell.

Or what matters is that there’s always more than just one path to the truth. The truth as it seems to be and the truth yet to come.

The narrator is working toward a confession — however, we’re also told that, “Every confession is a lie.” So whatever the narrator wants to confess, he’s also got several layers of story wrapped around it. And unreliable memory, and the inescapable alterations that begin to build up around any event that has happened in the past. Not to mention the consusions and twistings of the present story, this new dead redhead and what her relationship to Blake may or may not be.

The book also contains several, however indirect, references to Kafka, his writing and his life — the jackdaw, the monstrous father, subtle echoes of the story “The Judgment” with its mixture of drowning and sex.

Ultimately, despite my discomfort with the way the sexual violence of Breakfast at Midnight is handled, discovering a writer like Armand (not to mention this publisher — the Prague-based, English-language Equus Press) is really exciting. I almost would have preferred a deeper familiarity with Armand’s work — he has three other novels and seven poetry collections — before reading and writing about Breakfast at Midnight, yet this book most definitely persuades me to read further into Armand’s literary vision, both stylistic and moral, and to delight in a publisher with such provocative, well-written, avant-garde literature on offer.

+++

+