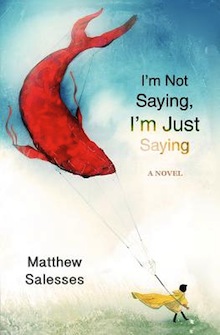

Our Research Notes series invites authors to describe their research for a recent book, with “research” defined as broadly as they like. This week, Matthew Salesses writes about I’m Not Saying, I’m Just Saying (Civil Coping Mechanisms).

+

I remember an episode of House in which a man suffers some brain disorder that inhibits his ability to filter his thoughts, so that he says whatever comes to mind. Often what he says is horrible; his wife hovers on the brink of leaving him. But the situation makes for an interesting character, full of conflict, naked and knowable.

I remember an episode of House in which a man suffers some brain disorder that inhibits his ability to filter his thoughts, so that he says whatever comes to mind. Often what he says is horrible; his wife hovers on the brink of leaving him. But the situation makes for an interesting character, full of conflict, naked and knowable.

When I was writing my novel, I’m Not Saying, I’m Just Saying, the research I did was like giving myself that brain disorder. I researched my worst self. I wanted to get at my vulnerabilities and what I might do to cover them up if I weren’t constrained by the morality of the real world. That is, if I were a fiction.

When I teach writing, a common encouragement I give is to be harder on one’s characters. The characters we write are not real — is an obvious distinction, but is an important one to make and to remember. Because for many writers, we write because our characters feel real. Sometimes that means we don’t want terrible things to happen to them; we don’t want to make terrible things happen to them; we feel bad about letting them act badly. Sometimes we even fear people reading a character’s worst traits into the writer. But if we want our characters to be vivid and interesting, we need to be hard on them. We need to love our characters, but because we love them, we need to put them in danger, let them make complicated decisions, let them be more real than at a cocktail party, as real as their deepest inner lives.

In I’m Not Saying, I’m Just Saying, the narrator is a man with a serious commitment problem. He has a live-in girlfriend, “the wifely woman,” whom he loves but cheats on continually. He wants to be a better person but he also doesn’t want to be. To this narrator comes a 5-year-old son he didn’t know he had, conceived from a one-night stand. The boy’s mother is dying, leaving the narrator the sole parent. This means a test of our character’s vulnerabilities. He responds by both regressing and progressing, cheating more, trying to stop, getting jailed for a fight, doing drugs, drinking until he blacks out, leaving his son with his girlfriend so that he can go skiing with guy friends. He does all this to avoid pulling himself together and committing to a new life.

I wrote the first draft of I’m Not Saying, I’m Just Saying before my wife and I were talking about having kids. But a lot of these fears are my fears, if I dug deep into myself: the fear of a child as a surprise, the fear of being unable to love, or to commit to love, the fear of being a bad partner and father, and so on. A lot of the narrator’s actions are things I might do if I were to release my poorest instincts.

In the episode of House I mentioned, the patient begs his family to understand; he says that the things he is saying aren’t really him. But they are, of course. They are what he thinks, in some forbidden part of him. He would keep them hidden if he could. Yet what the disorder digs up, both the terrible thoughts and the desperate pleas for his family to see who he really is (i.e. who he is when unaffected by plot) is the stuff of a compelling character.

Research doesn’t always mean facts, history, science, jobs. One of the types of research we do as writers starts in the mirror. It starts when we remove (in our imaginations) that filter that stops us from admitting/acting on our vulnerabilities. It starts when we acknowledge the part of ourselves that makes the best story. Fiction means we must be hard on that person in the mirror, both the character and the part of that character that is ourselves.

+++