Spolia, 2013

Contemporary audiences, inoculated against splattering brains and shattering lives, know when to peep between their fingers, when to look away. How, then, is a writer to convey horror to an audience inured to horror? What tools can the writer use to shock us out of our complacency?

Daphne Gottlieb chooses form.

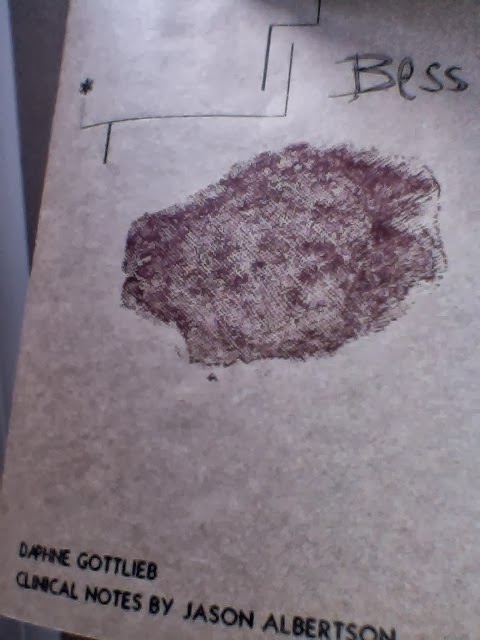

This chapbook consists of five sets of the clinical notes made by a Homeless Outreach team worker, complete with his explanatory footnotes; a narrative, which is enumerated in short paragraphs which sometimes correspond to hotel room numbers; and four stunning illustrations. It is not your average piece of writing, and it does not have average impact.

Bess, by Daphne Gottlieb, tells “the story of a girl lost in the labyrinth of addiction in the Tenderloin in San Francisco, and the case worker who must go in after her.”

The clinical notes, with their technical language and abbreviations, feel real, and in their bald, clinical realism they effectively cut through any learned strategies of avoidance we might reach for: “24 Y/O Cau.F., w. Menstrual blood on her willing to go to shelter at SFPD request.”

Footnotes provide a human interpretation of the clinical notes: “She doesn’t have anywhere to go, which makes her Homeless Outreach Team-eligible.”

The numbered paragraphs begin at 101, with its echoes of Orwell’s horror chamber for thought crimes, but also remind readers of the introduction to a subject within the American college system. Here, it is an introduction to the hotel, probably in the voice of the girl:

101. The hotel is not so big. It is not the biggest in the city, but is not the smallest. It is not the one that the serial killer lived in before getting caught, and it’s not the one that the woman who shot the famous artist lived in. It is a different one.

But as we move from one numbered paragraph to the next it is not always clear who is speaking; sometimes the girl, sometimes the care worker. Paragraph 103 is possibly the voice of an omniscient narrator, relating the Greek myth of the Minotaur imprisoned in a labyrinth, and Theseus unravelling a ball of red yarn behind him as he descends into the labyrinth, metaphor for the care worker descending into the Tenderloin to find and help the girl (a metaphor which doesn’t quite settle; possibly the only point at which the book falters for this reader).

107 begins in the care worker’s voice: “The girl needs help. She is a buttercup picked and left on the pavement for two days. She has been staying in a hotel room that belonged to her boyfriend, a drug dealer.” In the same paragraph, there is a shift into the girl’s consciousness: “You shoot straight into the blue string, not the red. The blue gets you lost.” Then, “The cops came” could be either voice, before we return to the care worker: “They said, take her. We did. It’s what we do.” And in paragraph 108 he continues: “This is what I do…”

We hear other voices too: the care worker’s supervisor, his colleague, a hotel manager, a cop, another hospital inmate, and the voices overlap and become layered and sometimes confusing, as they might seem to the drug addicted girl, Bess. It is this technique of voice slippage—combined with the form Gottlieb has chosen to convey the chaos of the lives of her subjects, the Tenderloin addicts—that makes it so affecting. Whether a story stays with the reader is often used as a metric by which to gauge its power; Bess stays, and disturbs, at many levels.

+++

+