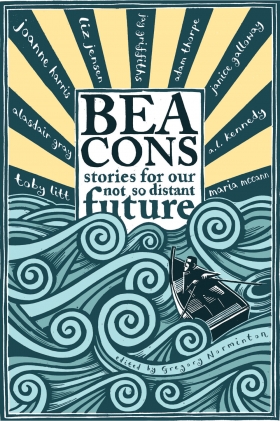

Oneworld Publications, 2013

Beacons is a refreshingly earnest anthology of short fiction commissioned for the dual purposes of raising funds for the Stop Climate Chaos Coalition and telling the stories that may motivate human civilization to act on behalf of our planet. No short order, and certainly one that begs the question: what can stories do to combat such a problem of global proportions?

Writes Editor Gregory Norminton in his introduction to the collection,

We have a collective duty to imagine what we fear to look at, for in looking away we fail, not only to avert the worst for our children, but also to create the happier and more just society in which we should wish them to live. More than ever we need stories that tell us where we stand, that help us imagine our predicament. Let them serve as beacons to warn of approaching danger, to unite us against adversity, to celebrate what we have and, perhaps, to show a path away from harm.

The resulting book consists of 21 stories organized in three different sections of seven stories apiece, a pleasing symmetry that brings an orderly, almost triptych feel to the chaos rioting in these works of alternately dystopian, satirical and historical short stories. Norminton makes clear in his introduction that this work shouldn’t be read as either polemic or policy. Instead, these fictions are designed to widen our understanding of a world slowly coming apart, and the myriad consequences of the actions we, as a global society, have or have yet to take.

The first section, “Looking in the Mirror,” offers seven stories that show characters dealing with their daily lives while the threat of imminent disaster menaces at the edge of nearly every interaction. Liz Jensen’s “Mother’s Moon Job” is a standout, featuring a young narrator, Maxwell, the son of a foul-mouthed “Zero-Plus Non-Contributor” whom he finds sprawled beneath their balcony in the very first lines of the story: “When Ma had the accident it was me found her. Sand’s not as soft as it looks.” With his mother suddenly, violently, out of his life, Maxwell is reunited with his grandfather, or, in Jensen’s parlance, his “bio-dad’s bio-dad.” There are plenty of George Saunders-esque terms to keep up with in this story, but Jensen manages to weave a compelling, chilling tale about social class, media, and family, while building a world at once alien and familiar to our own.

Another highlight here is “We’re All Gonna Have the Blues” by Rodge Glass, which follows a once radical movement leader’s lackey stressing over the man’s binge drinking and public antics while keeping his fears of a sudden, sweeping flood forever bubbling on his mental backburner:

Jaro will smile as if he’s forgotten everything. The responsibility, the future, what we all know is coming. Then we’ll clink glasses, and the water will burst through the door.

The other two sections, “a Strand in the Web” and “Go Light” explore our complicity in climate change as well as possible avenues to live a life more in line with our natural surroundings. James Miller’s “What Is Left to See?” is a slightly unwieldy but intriguing collage that blends voices of the future and the present, narrative sentences and hashtags, and the sunken shell of Miami with an arid, impoverished Greece. Beneath the cognitive dissonance this story creates, Miller asks serious questions about the ways we can learn from each other, and the limits of cross-cultural understanding:

Did she want the truth, this American girl, when she sensed his sorrow? Did she want to be told how the soil turns to dust when it has not felt rain for ten years and the crops perish and all that is left are the skeletons of sheep and goats as war spreads, north and south and all around? What did she know of the bodies picked bare by ants, children ill with hunger-swollen bellies or the people forced from their dying land to great camps at the border? He had no words for the stories of the broken world.

A final noteworthy piece comes in the form of Nick Hayes’s charming comic, “The Possession of Lachlan Lubanach.” Fable-like and suspenseful, Hayes’s bold graphics depict a castle chief who owns all that he can see and keeps a cellar full of the bones of animals he’s dominated. Lubanach tirelessly pursues a rare animal, eventually leaving behind his horse, his clothes, even his weapon in what appears to be the final chase of his life. The inclusion of visual storytelling undoubtedly adds value to the collection; if anything, this medium is well-suited to exploring our almost childlike fears and hopes for heroism that climate change can elicit.

At turns humorous, harrowing, and only occasionally veering towards the pedantic, Beacons captures a number of well-written stories that voice versions of the future worth considering.

+++

+

+