University of Alabama Press, 2009

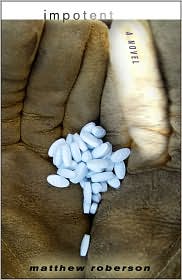

On the cover, a handful of pills piled into the crevice made by the cupping of two gloved hands. Inside, a novel of individuals and families, of their different medications, both prescribed and over-the-counter, and the myriad problems these “typical” Americans use as crutches. The novel is also an attempt to capture and reveal the banality of American life.

The first chapter of Impotent is more or less an introduction to a slew of different drugs and medications used by L.— L. stands for “Last Name, First Name, Middle Initial.” Each of the novel’s central characters, instead of being attributed a name like John or Bobby, is labeled like this. This labeling creates a distance between the reader and the character, but it also serves to illustrate how an individual may come to be dehumanized by medical or insurance companies. Roberson’s choice in naming his characters this way is a means of ridiculing that tendency. These are case studies. Names on a medical file. Though it is hard to keep track of the characters with this method, each chapter goes on long enough and reiterates the name often enough that eventually the reader settles into the idea.

Unlike the multi-paragraph standard form of most novels, every page of Impotent is engaging and exciting by its very format. At the bottom of almost every page is a short description (sometimes long) to which the reader is directed by a footnote. However, unlike a traditional annotated work of nonfiction, Roberson uses these notes, sometimes themselves footnoted, to expand the text, to simply keep the story going or to provide a quick flashback. Often, the annotations at the bottom of the page are nothing more than a continuation of the sentence or paragraph from which they began. For instance, on page 92:

E. didn’t want to forget she liked the newspaper, and that she liked chili with jalapeños and talking to her sister on the phone at night.42 She enjoyed sex once.43

It changes you, she said.

42 After only a little of the Times on Sunday, E. lost focus and started thinking of mowing the lawn, and she didn’t like kidney beans anymore. She couldn’t ever, ever stay up past ten.¹

¹Continue to take parozetine and talk to your doctor if you experience:

• impaired concentration;

• changes in appetite or weight;

• sleepiness or insomnia; or

• decreased sex drive, impotence, or difficulty having an orgasm.

Side effects other than those listed here may also occur.

43 but lately her clitoris had less feeling than a pinky toe.

The entire novel is constructed in this experimental format. One section even forces the reader to turn the book sideways in order to read it. In this fashion, Roberson engages his readers playfully, even aggressively. He pushes the reader into a discontinuous reading experience, which some may find off-putting. This, it seems, is the point. Reading pill bottle label after pill bottle label is much like this process. This is just one element of Roberson’s satirical take on the entire world of medical procedures, and it fits well with the content of the book.

Roberson’s chapters are essentially separate stories. None of them ease into each other or are related to any other story besides their connection to his apparent point and aim of the novel. Each chapter serves to exemplify another aspect of what the novel portrays as a very dreary American lifestyle. One of sex, drugs, and… the depressing drone of family life. The page directly following the one above says it all:

I wasn’t always fat as a house, L. said.

You’re not, said E.

Kids change us, L. said. Age changes us. Jobs. Friends.

I know, E. said.

This true-to-life, conversational tone of these characters’ speech is present throughout the novel, and Roberson does an excellent job of making each character both mundane and believable. The same tone is also employed by the narrator, which is always in third person. That tone is important. It not only helps to tie the different chapters and corresponding families together, but it creates a continuous echo of the novel’s theme. It is a constant hum, a weary but recognizable mood that American families know very intimately.

While the content showcases the mundane, the writing style, the format, and the pacing all keep the reading drive in third gear. Impotent is a fun, quick novel with a lot to say about the dependency Americans have on pills and problems, the system therein, and the countless frustrations and dissatisfactions of family life.

+++