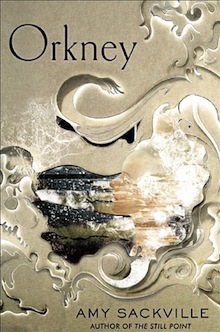

Our Research Notes series invites authors to describe their research for a recent book, with “research” defined as broadly as they like. This week, Amy Sackville writes about Orkney, out now from Counterpoint Press.

+

My approach to research is scattergun, catholic, greedy; I don’t know what I’m looking for until I find it, and what I find makes me want to keep looking. Research is all about questions, and questions only feed curiosity. I am not looking for answers. This is, for me, the most intensely creative phase of writing, and although the bulk of the work is done in the early stages of a project I don’t stop referring back, checking, and searching further, throughout the whole of the writing process. But the early part is the best, when a kind of procrastinating, anxious, restless energy has me straying from desk to sofa to chair to window, gleaning and muttering and cross-referencing and note-taking and, at the same time, writing, in snatches and bursts. For me, inspiration is about making connections — about colliding ideas, interests, sources, and sentences together — and feeling these things slide about and rub up and spark off each other and come out as words is thrilling. Reading a folktale and thinking ‘I can use that!’ and how I might do so. Finding echoes of my own half-formed ideas in a poem or a ship’s log or a map.

My approach to research is scattergun, catholic, greedy; I don’t know what I’m looking for until I find it, and what I find makes me want to keep looking. Research is all about questions, and questions only feed curiosity. I am not looking for answers. This is, for me, the most intensely creative phase of writing, and although the bulk of the work is done in the early stages of a project I don’t stop referring back, checking, and searching further, throughout the whole of the writing process. But the early part is the best, when a kind of procrastinating, anxious, restless energy has me straying from desk to sofa to chair to window, gleaning and muttering and cross-referencing and note-taking and, at the same time, writing, in snatches and bursts. For me, inspiration is about making connections — about colliding ideas, interests, sources, and sentences together — and feeling these things slide about and rub up and spark off each other and come out as words is thrilling. Reading a folktale and thinking ‘I can use that!’ and how I might do so. Finding echoes of my own half-formed ideas in a poem or a ship’s log or a map.

I use my writing journal to record and reflect on this process, and my own thoughts and digressions are interspersed messily with my notes. Sometimes a scrappy asterisk will mark a point to come back to, a new question I want to ask myself. I make lists — of, for example, all the witches, enchantresses, and enchanted creatures I can think of or have found clues to:

- Undine

- Vivien

- La Belle Dame

- Lorelei?

- Circe

- Eurydice?

- Lilith?

- Medusa

- Nereides, Tritons

- Sirens (Odyssey)

- Melusine

- Marian — sea goddess

- Artemis as fish-goddess?

- Elaine/The Lady of Shallott

- Selene (Endymion)?

- Coleridge — Christabel?

I make my way to the British Library and pile up books: Undine by Friedrich de la Motte Fouqué in the beautiful Rackham-illustrated printing of 1909. A pamphlet edition of Matthew Arnold’s ‘The Forsaken Merman’. A couple of lit crits on enchantment narratives and female monsters in the nineteenth century, of the sort that my protagonist might read, or even write. At home, at all times to one side of me: Tennyson, Keats, Browning. If a text is a tissue of quotations, and if a character is a kind of text, then this is the stuff that Richard, the first-person narrator of Orkney, weaves his wife out of. He is a professor who marries his student — a cliché, perhaps, but this is in itself another kind of received text, which like a fairy tale can be made use of, and reinvented.

I think I always start with place, with an idea of place. My first book, The Still Point, was set in the Arctic, a place I have never been. I had to construct it from my reading and my own imagination — but since I was interested in the ways in which this most illusory and shifting of places is figured in the imagination anyway, I felt justified. And I couldn’t afford to go. But thanks to a small funding grant I could afford to go to Orkney, to the island of Westray on the far Northwest of the peninsula. So this was another aspect of my research — being in that place and attending to it. The Orcadian dialect has many splendid words for the weather, and most of them mean something to do with wind, or mist, or rain. Gushel, skuther, skreevar. Muggry, attry days; and when it brightens, it is glettan. The most distinctive feature of the climate is the way it changes — the way the sky, the sea, the wind, the light changes, hour to hour. I wrote down all that I saw and I put those descriptions in my book, with little alteration, so that Richard is observing in the moment just as I did.

Richard’s wife has a connection to Orkney; they are there because she asks to be taken there on honeymoon. It is a connection that is never fully explained because Richard himself can’t fully access or understand it. It is something that she either can’t articulate, or wants to keep for herself. I want to make this connection felt in the text, through the gaps in it. So, there is a pile of books at my other side: a number of histories of the Orkney Islands. Various compilations of Orkney folklore. I feel deliciously absurd reading a children’s picture book in the Reading Room among all the proper scholars. This version of ‘The Selkie Wife’ gives me Old Tom, combing the beach, offering his warnings to besotted crofters, drunk and wise. I store him away and later find a place for him. An Orkney Anthology, the selected writings of the journalist and historian Ernest Walker Marwick, I think now sadly out of print. Edwin Muir. Eric Linklater. George Mackay Brown, the Orkney poet who is my constant, silent companion throughout the writing of this book. These are the texts through which I read the islands: their landscape, history, culture, myths, language, and all of the ways in which these things interrelate and overlap. This is what fascinates me about the place. The layering of meaning, the fluidity of interpretation, the constant draw of the sea that determines the rhythm of life and of the text.

From the outset I have in my mind that this book will be structured around a tension — between presence and absence, between the known and unknown, the written and unwritten, the word and the blank page. Richard’s wife is a space in the text that he is trying to write into, not necessarily successfully. I want to find a way to explore, through fiction, the same research questions that I wanted to ask when I was a student; I want to find a way to wear this lightly. Early in the process I go back to literary theory — I take my epigraph from Cixous: ‘The portrait of a story attacked from all sides, that attacks itself and in the end gets away.’ I keep this in the back of my mind, so that it speaks to all of the other stories I pick up and make use of and leave behind me, so that it is for the reader to find their own connections, to hear their own echoes.

+++