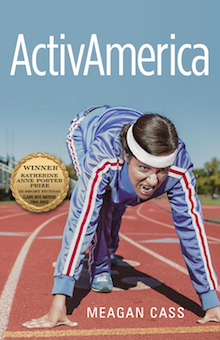

Texas A&M University Press, 2017

Sports reveal those who play them. Think of your days as a gymnast, or a little leaguer, or a pee-wee football player. Did you, as some characters in Meagan Cass’ debut collection ActivAmerica do, pass the ball as soon as you received it, too afraid to fail to score? Did you lift weights to sink deeper into yourself, using self-improvement as a way to hide from a disappointing life? Did you take to the court, throwing elbows because you were angry about things you didn’t yet understand?

In ActivAmerica, which is the 2017 winner of the Katherine Anne Porter Prize in short fiction, Cass uses sports and athleticism to draw out her characters’ true mettle. Take, for example, the story “The Hawthorne Dynasty”. Two girls who played soccer together as children grow up to lead different lives defined by privilege and poverty. The narrator is relatively privileged, but her friend, a superior athlete, is labeled early on as “white trash” and she’s also browbeaten by her mother, a trauma that proves too great to overcome. The narrator, who envies her friend’s talent, describes her own style of playing: “I was a tentative left wing, unable to hold the ball for long, always passing it to someone else as soon as I got it. It was years before I understood this as a variation on cowardice, a kind of emotional flinch.” Years later, the narrator realizes how much of a “dick” she has been to her former friend and attempts a reconciliation, but settles for a half-hearted and cowardly attempt to experience her poor friend’s life. It is a portrait of guilt, envy, class, and bad parenting.

Many of these stories take place in Hawthorne, New York, just north of New York City, in a place suburban enough to sprout an abundance of soccer teams. In Hawthorne (or other similar communities), it’s nearly impossible to not run into a family torn apart by divorce. In “Jews in Sports,” a young man struggles to build a relationship with his father, who has left the family, and who had unrealized athletic dreams for his son. In “How Mary Lou Retton Took Over Our Lives in the Summer of 1994,” a mother’s absence seems to inspire in her daughters the desire to conjure apparent hallucinations of the Olympian in the backyard. Children in ActivAmerica suffer greatly at the hands of parents whose lives have gone off the rails.

But if the parents in Cass’s stories are sometimes wayward and unreliable, they also can be far too demanding. “A Parents’ Guide to UltraSport Children” takes this notion to the extreme. This guide for parents attempting to bring children into their new “UltraSport” bodies distills a whole industry that seems to be dedicated to erasing children’s happiness in an attempt to enhance it through athletics. This parental effort, of course, is not about sports or about the children’s well-being. “Your UltraSport children are now part of an elite tribe,” the guide says. “You are part of that tribe, too.”

Most of the stories found in ActivAmerica are longish, plotted narratives, but Cass departs from those with a few bits of flash fiction that rely less on plot than on the music of language and close observation. “Portrait of My Father as a Foosball Man, 1972-2012” is the three-page story of how it might feel to be a little plastic foosball man, hovering over a plastic soccer field, inches from other similar men he will never touch. Cass finishes this character study with a paragraph that rises and falls in a final crescendo:

Don’t get him wrong — he does not want to move like you or I, does not share the Little Mermaid’s naïve desire to be transformed, to have his single leg split, to dance a ballroom waltz with a gowned bride, to be part of our world and all that crap. It’s just that it’s been so long since anyone turned his metal spoke heart with purpose, so long since he’s shone his twitchy, hummingbird grace, so long since he’s listened to human players laugh and talk smack and howl in victory and defeat, the way real players on real, muddy fields must howl, he used to figure, like it mattered more than anything else, more than having parents who loved each other and loved you, more than beauty and being cool, more than high cholesterol, more than looming dementia, howls so loud and so deep they reverberated through the whole table, seemed to come from him.

The lyricism found here also carries another flash piece, “Interview with the Ghost of Jaws’ First Victim,” in which the female narrator starts with blunt force (“What I wanted was to get laid”) and ends with more sentences designed to paint a portrait of innocent life cut short. “Tell my mother I was beautiful before the end, my body beautiful before the end, my body backlit with moonlight, my long hair waving. Tell my father I actually liked cribbage. Tell my sister to stop plucking above her eyebrows, to be wary of boys from Connecticut.”

Overall, though, in these stories — both the straight-forward narratives and the concise, musical vignettes — we see average American people releasing through sports emotions they don’t always understand, using sports to find a way to simply stop “suffocating” in their own lives, perpetually tempted to believe that “that happiness is just a matter of pushing through the bad nights, tamping down the errant dreams, of trying, just a little harder, to hold a certain version of yourself together.” These characters become human in their desire to be loved and valued, and their flawed assumption that they’ll get there if only they’re healthier or better at a game only makes them more endearing.

+++

+