“I grew up in a country whose language is spoken by fewer than nine million people. Most of the literature that shaped me as a reader and an individual, and later as a writer, was in translation, mostly English works in Bulgarian. This translation of 18% Gray from Bulgarian to English is, in a way, my chance to give back what’s been borrowed, a raindrop returning to the ocean it came from.”

– Zachary Karabashliev in the postscript to 18% Gray

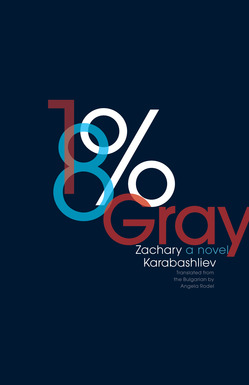

Open Letter Books, 2013

18% Gray, with the exception of some early flashbacks, is set in the United States of America. The first person narrator is (like the author) named Zack. Both Zacks are Bulgarian. They both immigrated to America and settled in California. Character Zack journeyed there with his wife, Stella. Author Zack… I’ve no idea, but would guess the same.

Zack’s world has already imploded by the time we’re introduced. Stella has left him. He crosses the border for a wild night in Tijuana and returns with a trunk full of marijuana. An acknowledged expert at compounding bad decisions, he decides to drive the bag of drugs cross-country and sell it in New York City.

But all that’s just the narrative framework. Interwoven into this storyline are flashbacks in which Zack replays the history of his & Stella’s relationship. How they met in art school; the fall of Communism; Zack’s dreams of becoming a rock star which are eventually abandoned in favor of a career in photography; their marriage and immigration; the life they built; and finally, the rise of Stella’s art career running parallel to the deterioration of their relationship.

Separate from the flashbacks and the “framing” plot are isolated scraps of dialogue—broken conversations between Stella and Zack—which happen as she poses for his photographs. As a person and a character, Stella remains on the periphery of 18% Gray. Like the Lisbon sisters in Jeffrey Eugenides’s The Virgin Suicides, we only see and understand Stella through the lens of Zack’s male ego. The Stella we meet is a projection—pieced together out of Zack’s half-memories, desire and regrets. Eventually even Zack realizes this.

As if this wasn’t ambitious enough, there’s still another layer to this novel. Zack finds an old Nikon camera (the kind that uses film) at a pawn shop. He uses it to build a visual diary of his cross-country roadtrip. The images he takes (much like Zack, himself) simultaneously mesmerize and repulse us.

From the drugstore across the street two girls come out and head toward the coffee shop. They cross the street and sit at a table on the corner. The first one is blonde and pretty-pony tail, cut-off jeans, a little red tank top revealing her navel, blue flip-flops, oversized sunglasses, sucking a milkshake from a large plastic cup with a straw. The other one, chubby, also wearing sunglasses, starts reading something aloud from a fashion magazine. The biker in black reappears from the shop with a Coca-Cola in hand and slowly approaches his motorbike. I now notice that he has a knife stuck in his other boot as well. The chubby girl lifts her greenish-yellow mirrored glasses from the magazine and looks toward the biker. I can’t see his response because he is already in front of the bike with his back toward me. He just stands there sipping his Coke. Then, in the middle of the scorching intersection, another kid appears. He crosses the street unhurriedly and stops at an empty table. His hair is fair, parted in the middle, his face covered with red, agitated pimples. He is wearing an Iron Maiden T-shirt, camouflage pants, and white sneakers. He drags a chair, sits down, and starts monitoring the intersection carefully, without ordering anything.

For one much extended moment, all of these figures are still and silent. I have a feeling that I am in someone else’s bad dream. I choose to leave it and get into my car. From there, I manage to snap a few shots of the still-unmoving figures and head back toward the freeway which will take me away from here.

Karabashliev is a writer who’s intent on playing a long game. It requires a certain amount of patience from his readers. 18% Gray really only develops into something tangible 100 pages in. Karabashliev has created an emotionally compelling novel out of disparate ideas and elements, making them work together through sheer force of will. But this takes time. No detail is extraneous. And Angela Rodel’s translation juggles it all, making it seem effortless.

Even without the postscript it’s obvious that Karabashliev has a strong foundation in English literature. In addition to Eugenides, he reminded me of authors as disparate as Nick Hornby, Jack Kerouac and even Charles Portis at his picaresque best. Not because of any homage or even obvious commonalities. Rather, they all seem to be sharing the same reading list. Zachary Karabashliev, though, is unique in that he’s decided to throw all he’s learned into one book. Even more impressive, he’s successful—driving readers toward an emotionally devastating ending. It’s hard not to read 18% Gray as a love letter to the great American novel. The great American novel as interpreted by a Bulgarian author, living in San Diego. When you think about it, it doesn’t get more American than that.

+++

+

+