Our Translation Notes series invites literary translators to describe the process of bringing a recent book into English, or to offer perspectives on global literatures from which they translate. In this installment, Rachel Miranda Feingold writes about editing and adapting Hana Adronikova’s The Sound of the Sundial, translated from the Czech by David Short, for Plamen Press. Portions of this essay have been excerpted from the Editors’ Note at the beginning of The Sound of the Sundial.

+

Chasing the Sun: Working with Hana Andronikova’s The Sound of the Sundial

I first experienced the English language as something intimate and familial. I was born in Zurich, the middle child of American expatriates, and while my parents spoke and read English to me, I conversed with my childhood friends in a spoken-only dialect called Schwiitzerdütsch (Swiss German). To further complicate matters, we were required to use the more formal written language of Hochdeutsch (High German) in school. In this way, my early linguistic world was divided in three, and I became aware at a young age of the mysterious differences between the way we read, speak, and write.

I love the lyricism and exactness of English, and yet I am frequently drawn to the translated novels in which I can hear the echoes of my childhood. I became a writer in midlife, when I finally admitted that all I had ever wanted was to be at play in the English language. I became a translation editor at the same time, because I did not want to relinquish my right to dance among the grey spaces between the words and their meanings.

I met Roman Kostovski in 2014 at a meeting of the DC-Area Literary Translators, shortly after I had moved to Washington, DC (another part of my midlife shift). Roman is a Czech native and a linguist with ten languages under his belt, and at the time, had just founded Plamen Press as a vehicle for the abundance of Eastern and Central European literature, both classic and contemporary, that has yet to be translated. He was there in search of an editor who could render the academic translation of a brilliant Czech novel into more lyrical English to reflect the tone of the original.

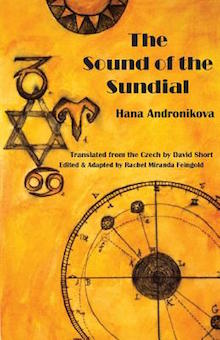

The novel was The Sound of the Sundial by Hana Andronikova, inaugural winner of the Czech Republic’s highest literary award, the Magnesia Litera, in 2001. It was a huge book in many respects, and it had landed on Roman’s virtual doorstep almost immediately after he founded Plamen Press.

I did not know a word of Czech when I began working on The Sound of the Sundial. Luckily, Roman viewed this as an asset, because my ignorance would allow me to see where the highly conceptual Czech language with its fluid tenses needed to be altered for readers of our far-more-concrete English. This process was complicated by an interesting conundrum: there were two translations to work with, and they were very different. The first manuscript, by British linguist David Short, was thorough and precise, but had lost much of the luminous immediacy of Hana’s style. The second manuscript departed dramatically from the first, but it could not be ignored either, since it used the Short translation as a starting point, and had been heavily edited and adapted by Hana herself, in partnership with an American editor, Ian Miller. This version restored the book’s lyrical tone, but eliminated whole sections of the original in an apparent effort to reduce the story’s large number of shifts in time and point of view.

Neither of these translations ever saw the light of day. Why not, I wondered? This was just one of many mysteries that arose during the course of my work on Sundial; they tugged at me in unexpected ways, turning a juicy professional challenge into a personal quest.

Hana was quite fluent in English, having studied English Literature as an undergraduate, and later spending a year at the Iowa International Writer’s Program where she wrote some remarkable stories in original English. Still, that second translation of Sundial was so deeply cut, we felt it had lost important character nuances, and we couldn’t help viewing the absence of a published version as a sign of Hana’s own ambivalence. Yet we knew it had been her dream to publish the novel in English. Might she have reconsidered if she had had more time?

How often I wished that I could call Hana and ask her these questions! She and I were contemporaries, born just seventeen months apart, and I had started to feel as if we could be friends. But of course this was impossible. I first laid eyes on The Sound of the Sundial in November 2014; Hana Andronikova had lost her battle with breast cancer on December 20, 2011.

So, it was up to Roman and me to decide what to do. Ultimately, we felt that we had to take all of Hana’s original words into account. We went back to the first translation, and—keeping the second one always in our sights—began blending the two. We met for hours each week, so Roman could make sure I didn’t stray too far from the original in my efforts to do justice to Hana’s vivid writing, and so we could honor her use of time as a structural element without losing the reader. She treated time as a sort of loom on which characters shuttled back and forth, much in the way we might experience life from moment to moment: the unfolding events of the present are endlessly interwoven with ribbons of memory and emotion from the past, to create the rich tapestry of human experience.

The Sound of the Sundial is a sweeping historical fiction, shot through with passages in Colorado in 1989, but playing out primarily in the 1930s and ’40s in Central Europe and India. Though its scope is broad, it is also an intimate love story about the marriage of a Czech-German called Thomas, and a fiercely independent Czech Jew called Rachel. Thomas Keppler is a building engineer who works for the Bat’a Shoe Company, a real-life industrial dynasty that has its roots in the Czechoslovakian town of Zlin, which in 1930 was, in Andronikova’s words, “a city of unheard-of opportunity where… Bat’a’s factory employed over six thousand people and produced thirty-five thousand pairs of shoes a day.”

This was a place Hana knew well, as it was her hometown. Zlin arose out of Bat’a’s vision of a community built to serve every need of the growing company at its center—a leather processing plant, proper housing for every worker, a cinema, even a cemetery—all to maintain focus on the dream: affordable shoes for everyone in the world.

These historical details appear in the early pages of Sundial, integral to the portrait of the Kepplers’ life as a young couple. With them we travel to Calcutta, where Thomas has been sent as one of “Bat’a’s Young Men” to spread the shoe empire over three continents. Rachel soon falls under India’s spell, and writes a letter to her sister:

The Orient enchants me…no one’s in a hurry, no one makes plans, cows meander through the streets in a flood of sounds and colors like an endless carnival, one costume more imaginative than the next. Everything here is in color, even the air. In the daytime it shimmers in the glinting golden sunlight. And the night—the night is blue. You bathe in a magical blue that turns reality into dreams and dreams into reality.

Most of the details of life in India are animated through the reminiscences of Daniel, Thomas and Rachel’s son, in the modern-day segments that bookend the story. Daniel, already a grandfather, tells of a chance encounter during a family vacation in Colorado that allows him to finally assemble the missing pieces of his mother’s fate, a mystery that has haunted him since her disappearance—like that of most Czechoslovakian Jews—during World War II.

In Colorado, Daniel stumbles upon Anna Vanier, who had met his mother in the concentration camps and become her dearest friend there. Intermittent chapters in Anna’s voice trace Rachel’s footsteps through three different camps—Theresienstadt, Auschwitz, and Bergen-Belsen—with their surprisingly varied cultures. This is how we learn of her fate.

Reading these chapters for the first time, I wondered why Hana had chosen to write a Holocaust story, and why these passages felt less like words of imagination than words of witness. Hana was not a Jew, nor had she been alive during that dark time. Here was another mystery, one for which Roman, as a Czech native, could provide part of the answer: he explained that this fated love story of a Czech-German and his Jewish wife was also a metaphor for the close cultural relationship of the German, Jewish, and Czech people, who were permanently sundered by the war, leaving the country’s cultural identity in a fractured state from which the Czechs are still recovering. Hana was asking: Who are we, after our loved ones disappear from our midst? For me, as the granddaughter of Eastern European Jews, this was a new view of familiar territory, and I was hooked. I simply had to find out more about her.

As soon as I got word that I had been accepted for a 2015 Prague Summer Writing Fellowship, I contacted the agent for Hana’s estate who had sent the manuscripts to Plamen Press, and he put me in touch with her family. During my month in the Czech Republic, I met with over a dozen people who knew and loved Hana Andronikova—literary figures and relatives, old friends and admirers—and I began to form a picture of her life.

Hana’s sister, Eva, invited me to come to Zlin, which looked exactly as Hana had portrayed it: a city comprised of thousands of little workers’ houses scattered around a central square, with carefully planned roads and businesses, and the name Bat’a everywhere. “Bat’a Lives!” declared a poster for a 2013 documentary still hanging in the town center, though the industrial tycoon had died spectacularly in a 1932 plane crash, also described in Sundial.

I met Eva at their childhood home, in which she now lives with her own family amidst memories of her sister, whom she adored. Eva served me a traditional Czech meal of potato onion soup and fresh apricot dumplings while she told me Hana’s personal reason for writing the novel: in her mid-thirties, recently married and working successfully in the corporate financial sector, Hana began to have nightmares of being a concentration camp inmate, a victim of the dreaded Dr. Mengele. The dreams came back again and again, and though she had always been a practical person, she began to wonder if they were buried memories of a past life. With no answer to such a paranormal question, she read everything she could find about that time, and characters began to take shape as she wrote down what she learned. She told her husband this was the most important work she had ever done, quit her job, closed the door to her study, and wrote. By the time she finished the novel, three years had passed, and she was so changed by the process that she walked away from her marriage as well.

Hearing this, I felt closer than ever to Hana, as we had this in common, too: trying to face our deepest fears on the page, we both found that we had written ourselves right out of our marriages. And now I finally understood the eyewitness tone of passages like this one, in the voice of Anna Vanier during her time in Auschwitz with Rachel:

The three-story bunks were like cages, the cold, the smell of chlorinated lime, and bodies, and latrines. Bedbugs. We climbed onto the top bunk and huddled close to one another…My head was full of smoke. It dawned on me where all of the autumn transports had ended up, and I felt sick. Rachel told me that myths were memories of the life we wanted to live.

The “myths” here are Mayan myths of the sun, ancient stories Rachel tells Daniel when he is a small boy, and tells again to her fellow concentration camp inmates. This was another mystery I wanted to solve: why had Hana been obsessed with ancient Mayan myths? I learned the answer from her ex-husband, Michael Andronikov, who returned from a business trip on my last day in Prague, and offered to drive me to the airport so I would have time to interview him. He was proud of Hana’s work, he said, even though the marriage had been a casualty of it.

Michael told me that during their newlywed years, when they both worked excessive hours in their corporate jobs, they would take month-long winter holidays in Mexico. There Hana, who—like most Czechs—had an entirely secular sensibility, was strangely drawn to the Mayan temples. She and Michael would go in the empty, early morning hours, and Hana would close her eyes and sense the profound power of those places. Even then, Michael said, something within her began to change.

Hana’s friends, who described her as immensely intelligent and highly intuitive, remarked that she seemed to know there would be a mortal struggle for which she needed this deeper spiritual understanding. The Sound of the Sundial was published six years before Hana’s cancer diagnosis, yet there is an eerie prescience in Rachel Keppler’s bid to find meaning for her short life. Maybe even more telling are the passages about Hindu attitudes toward death, concepts that Rachel comes to understand in the 1930s, not knowing that she, too, will need them soon. Hana seemed to be comforting her own future self when she wrote: “India does not obsess over immortality. On the contrary: every Hindu yearns to obtain moksha, liberation from samsara, the endless chain of birth and death.”

Like her heroine, Hana Andronikova was fiercely determined, a perfectionist as well as an optimist. Once I understood this about her, I could see why—despite the national acclaim this book received in the Czech Republic—no English translation had ever been published: when she died, Hana must still have been searching for a solution that would satisfy the missing elements in the two existing manuscripts. Her devoted friends assured me, often tearfully, that she would have been pleased with our work—and I can only hope they’re right.

It almost goes without saying that these anecdotes are building blocks for a book about Hana. But there is a critical element missing: her second and final novel, Heaven Has No Ground, which has yet to be translated, and without which I can’t tell her story.

Hana was so driven to come to terms with life’s unanswerable questions that even after learning she was ill, she delayed medical treatment to continue her quest—with a shaman in the Amazon jungle, then wandering in the Nevada desert, then with an Israeli guide on Mount Masada. During the ten hopeful months when she believed she had beaten the cancer, she fictionalized this journey in Heaven Has No Ground, an instant bestseller that won the Magnesia Litera again just weeks before she died. She was 44.

Plamen Press has acquired the translation rights to the novel. Roman will do the translation himself, and I will once again do my editor’s dance in the spaces between the words; we were thrilled to learn, last month, that the National Endowment for the Arts has granted us a 2017 Literature Translation Fellowship for the project. We are ready to begin.

Meanwhile, there is The Sound of the Sundial, Hana’s love song to the range of human experience, with all of its suffering and cruelty and loss, and its moments of irrepressible joy.

+++

Born in Zlín, Czech Republic in 1967, Hana Andronikova studied English and Czech literature at Charles University in Prague. She turned to writing full time after many years of working in the corporate financial sector, and won instant acclaim for her first novel, The Sound of the Sundial (Knižní klub, 2001) receiving the Czech Book Club Literary Award and the Magnesia Litera Award for Best New Discovery in 2002. Her book of short stories, Heart on a Hook (Petrov, 2002), cemented her national literary reputation, and in 2007 she was sponsored by the U.S. State Department to attend the International Writing Program at the prestigious Iowa Writers’ Workshop. Her book Heaven Has No Ground (Odeon, 2010) is a personal chronicle of her fight with breast cancer and the looming possibility of death. For this work, she won the Magnesia Litera again in 2011, but lost the battle for her life at the end of that same year. She was 44 years old.

+

Rachel Miranda Feingold is an adjunct instructor in Writing for the Arts at the University of Maryland, a writer/editor for American University publications, and an editor of translated Eastern and Central European literature at Plamen Press in Washington, DC. She is a 2017 recipient of the Literature Translation Fellowship from the National Endowment for the Arts, and a 2015 recipient of the Prague Writing Fellowship. Her short story “Cerulean Blue” was published in the anthology Seeking Its Own Level (MOTESBooks, 2014), a Top-Five Finalist for Best Anthology in the 2015 Next Generation Indie Book Awards.