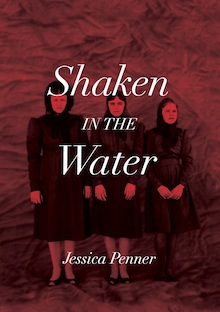

Our Research Notes series invites authors to describe their research for a recent book, with “research” defined as broadly as they like. This week, Jessica Penner writes about Shaken In The Water, out now from Foxhead Books.

+

My novel-in-stories, Shaken in the Water, takes place in a little Kansas town and spans three generations of a Mennonite farm family. I grew up in a similar town in Kansas, and am a descendant of immigrants from a similar Mennonite colony in the Ukraine, but I never wrote about Kansas until I moved to New York City, and the Mennonites in Shaken are like no Mennonites I’ve met.

My novel-in-stories, Shaken in the Water, takes place in a little Kansas town and spans three generations of a Mennonite farm family. I grew up in a similar town in Kansas, and am a descendant of immigrants from a similar Mennonite colony in the Ukraine, but I never wrote about Kansas until I moved to New York City, and the Mennonites in Shaken are like no Mennonites I’ve met.

Shaken is not a historical novel. It’s not even stuck in the particulars of the Mennonite faith; rather, it is part of my characters’ identity and their growth in — or away from — the heritage of a group of people who had spent the previous 500 years running from persecution. I based my stories on my own memory; I conducted minimal research, and that usually came after the core of the story was written. I was afraid the facts would get in the way of making the story my own.

The first story in the novel, “Tarred,” is based on a family story. A group of non-Mennonites surrounded my great-grandfather’s house and threatened to tar and feather him because he refused to buy war bonds during World War I. (Mennonites are, to varying degrees, pacifists. Buying war bonds directly supported something against his faith.) He and his family hid in the attic to save him from his fate. I first heard this story from my grandmother when I was in the fourth grade. I had fallen from a jungle gym and broke my leg. The break was so high on my femur I was encased in a partial body cast to keep it as immobile as possible, so I was stuck at home for several weeks.

Grandma Penner stayed with me during the day while my mother was at work. She sat next me and talked about her childhood. I heard about life during the Dust Bowl — a time when no matter how much they dusted in the morning, how tight they shut the doors and windows, dust always blanketed everything inside by evening. My grandma told me she had never finished high school because a male teacher told her she was too stupid to continue. She confessed that at her brother’s funeral she touched his face and was shocked by the hardness; a farmer bulldozed his grave years later. She told me the story about the night that men rode up to her father’s house with tar and feathers.

Those days of stories are my most intimate memories of Grandma Penner. It was during that brief period between discovering that my grandmother was a fascinating person and entering the sarcastic teen world when spending time with grandparents is so boring. Then I didn’t want to learn how to make peppernuts or zwiebach (traditional Russian Mennonite fare), or how to quilt. I regret not grabbing at those opportunities now. Grandma Penner never pushed me to learn these things. I wish she had. Why we even used such a formal name for her is unknown to me; I never learned an endearing reference. I wish that I had used Oma instead — German was the original language spoken by Mennonites — equivalent to Granny or Nana in English. I don’t know if that was introduced by her or my other grandparents. Grandma Penner knew Low German (a dialect used by Russian Mennonites), but she never taught my father and his sisters. One of my aunts told me that Grandma Penner and her sisters used it whenever they wanted to talk about something they didn’t want their children to hear. It was from the past, and I sensed that she didn’t want to have anything to do with the past.

Those days of stories were a rare gift. I don’t know what persuaded her to share them, to talk about the past. Maybe she didn’t know what else to say to a granddaughter encased in plaster while everyone else moved in their own lives.

When I decided to become a writer, I refrained from writing about Mennonites or living on the prairie. Somehow I got the idea that ignoring place and history was the best way to write fiction. My hometown is crawling with Mennonites. I went to a Mennonite university. I even lived in a house in New York City that was sponsored by a Mennonite church. My Mennonite past constantly surrounded me; it seemed too mundane and overused in Amish romances. Plus, Mennonites are obsessed with “truth” in collective memory. I couldn’t fathom writing even fiction where I’d get something “untrue” and have to defend it to the Mennonite reader. I wanted to write literature, not repeat histories.

I wrote a story about a pastor’s wife who butchered the church cat and submitted it for my a workshop at Sarah Lawrence College. This was my first experience writing even something remotely religious in a decidedly secular setting (this was confirmed by the poster in the cafeteria announcing an S&M workshop). To my relief, my classmates accepted it without batting an eye. I decided to try a Mennonite story — my grandmother’s story — with a twist. This story had a white tiger.

The first few drafts of “Tarred” attempted to be as accurate as possible (as far as the Mennonite-ness went, never mind the tiger), until my workshop professor told me to make it true to me, rather than hamper myself down with facts.

The finished draft of “Tarred” is seen through the eyes of a young woman, Huldah, who is shunned by her Mennonite church for refusing to wear a head covering; she claims that God gave her permission when she was swept up in the eye of a tornado. Everyone thinks Huldah is crazy, since she has “spells” and cannot read or write. Her parents beg her to quietly recover her head, but she refuses. A tiger begins to show up during Huldah’s spells, and tells her to aufpausse — wait — to stay in her community, live with her family that forces her to eat at her own table. The tiger tells her she will be needed. She learns how to use a gun — something that is forbidden. Her father refuses to buy war bonds. Men show up at her family’s home, her father hides, and Huldah gets her gun.

A writer once asked the oral historian Studs Terkel, in reference to how he turns forty-page transcribed interviews into only ten published pages: “How do you edit without hurting the truth?”

Terkel replied: “If anything, you highlight the truth. You get the essence of it. That becomes poetic… So the words are all the words of that person… you get the truth of that person italicized.”

There are no tornadoes, guns, spells, or tigers in the original story. But the heart of the story is true: the outsider is needed to grab what her faith rejects. My grandmother would have stridden out with a gun to stop those men, had she been old enough to hold one. My grandmother was an outsider — an uneducated young woman surrounded by educated men who forced her into one kind of life — but she would have done anything to protect her family.

She had been dead for nearly a decade by the time I wrote this story. I wonder how she would have liked it or any of the other stories. Probably she would wonder why I bothered with that old stuff, then why I added the drugs, sex, incest, and lesbians, but she probably would’ve read the whole book anyway. That’s what you do for your family.

+++