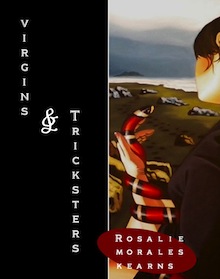

Our Research Notes series invites authors to describe their research for a recent book, with “research” defined as broadly as they like. This week, Rosalie Morales Kearns writes about Virgins & Tricksters (Aqueous Books).

+

Some might describe my fiction as magic realist, though I think it falls into other niches of the fantastic: magic-absurdism, perhaps, or whimsical grotesquery. So I don’t get asked much whether my work is autobiographical. Readers of my story collection Virgins and Tricksters probably guess that I haven’t danced through an an old-growth hemlock forest with a raggedy band of ghosts; or been confronted by disgruntled statues of the Virgin Mary.

Some might describe my fiction as magic realist, though I think it falls into other niches of the fantastic: magic-absurdism, perhaps, or whimsical grotesquery. So I don’t get asked much whether my work is autobiographical. Readers of my story collection Virgins and Tricksters probably guess that I haven’t danced through an an old-growth hemlock forest with a raggedy band of ghosts; or been confronted by disgruntled statues of the Virgin Mary.

But that doesn’t mean I don’t do research.

Take the hemlock forest story. Pilar Quiñones, the protagonist of “Devil Take the Hindmost,” is a geologist at the National Academy of Sciences. I’m no scientist, despite years of devoted NOVA watching, but while I was revising the story I had a visit from a cousin and her husband — a geologist, as luck would have it. I whisked him off to Bald Eagle State Forest, in Synder County, Pennsylvania, and trailed after him taking notes while he walked the very paths my character did (“What do you notice?” I kept asking him. “What jumps out at you?”). Books helped too, such as The Earth: A Very Short Introduction, by Martin Redfern.

Occasionally I take a book I’ve used for research and put in the hands of my characters. For example, Pilar finds a copy of The Annals of Snyder County from the early twentieth century, which explains the namesake of the forest’s Hairy John Picnic Area. Long story, that.

In “The Pirate’s Wife,” set in colonial North Carolina, some drunken pirate taverngoers read aloud from a stolen copy of Charles Johnson’s General History of the Pyrates (1724); its claim that the infamous Major Stede Bonnet went “a pyrating” to escape his nagging wife is particularly annoying to the title character.

Remedios, the main character of “Taínos at Large,” comes across a copy of Guillermo Baralt’s classic history of the Buena Vista coffee hacienda in Puerto Rico. She is as moved as I was by the photograph of the freed slave Ma Leoncia in old age, and the chart of fugitive slaves from the Ponce area: names, ages, dates of escape — but not the success or failure of the attempt.

I also inflicted on Remedios part of my own research process — the frustrating part. Remedios is an undergrad, majoring in biology, who wants to write an independent study paper on African influences in contemporary Puerto Rican spiritual practices. On a summer visit to Puerto Rico she schedules trips to various libraries, reads book after book, but finds either no mention at all of an Afro-Puerto Rican spiritual tradition, or authors who simply deny it exists (claiming that African-based practices began in Puerto Rico only in the 1960s, transmitted by Cubans via New York City).

It’s a sad fact that Puerto Rico’s African heritage is ignored more often than celebrated. My narrative solution was twofold: first, a mysterious blank book appears in every library Remedios visits, and finally she (and other anonymous contributors) start writing in it themselves, testifying to their own knowledge and experiences (for example, a list of “Important Concepts in Afro-Caribbean Philosophy,” such as egalitarianism, tolerance, reverence for knowledge). Second, the ancestral spirits of Remedios, who are in fact the narrators of the story, compose an alternative tourist brochure, describing the sites and attractions of what they call the Ghost Tour: a map of escape routes; a photo of a mangrove swamp where many escapees took refuge; a pristine beach from which, “according to legend, the woman known as Conga Maria flew back to Africa.”

That was my narrative solution. My solution as a person interested in the topic long before I wrote this story was to rely on a number of other sources. I’ve made many visits to Puerto Rico, my mother’s native country, including to the sites mentioned in the story: the coffee hacienda, the Caguana indigenous archeological site, the rainforest. dry forest, undeveloped beaches, mangrove swamps. The U.S. Geological Survey has lots of useful online information about Puerto Rico’s various ecosystems; so does the U.S. Forest Service, including a report with the delightful title “Champion Trees of Puerto Rico.”

To get glimpses of the lives of earlier Afro-Puerto Ricans, I had to rely on the excellent scholarly work by historians and economists who studied slavery and post-emancipation race relations, for example, Francisco Scarano’s Sugar and Slavery in Puerto Rico: The Plantation Economy of Ponce, 1800-1850. For specifics about contemporary spiritual practices, I found a couple of reputable documentaries, along with two memoirs by Marta Moreno Vega, The Altar of My Soul: The Living Traditions of Santería; and When the Spirits Dance Mambo: Growing Up Nuyorican in El Barrio. I also extrapolated from serious, evidence-based work on African-diaspora spiritual traditions elsewhere in the Caribbean. A superb scholarly work on Afro-Cuban spirituality is Wizards and Scientists: Explorations in Afro-Cuban Modernity and Tradition, by Stephan Palmié. The most fascinating (and bizarre) Cuban book is, sadly, unavailable in English: El Monte, by the ethnographer Lydia Cabrera, who in the 1930s and 1940s conducted interviews of elderly black Cubans about their beliefs and practices.

Some other good books on Afro-Caribbean spirituality in various locations (U.S., Cuba, Haiti) are:

- David D. Brown, Santeria Enthroned: Art, Ritual, and Innovation in an Afro-Cuban Religion.

- Margarite Fernández Olmos and Lizabeth Paravisini-Gebert, eds., Sacred Possessions: Vodou, Santería, Obeah, and the Caribbean.

- Karen McCarthy Brown, Mama Lola.

- Robert Farris Thompson, Flash of the Spirit: African and Afro-American Art and Philosophy.

In hindsight it’s not always easy to reconstruct what I had already read for my own interest and what I read later for more information. Almost all the reading I did for “The Pirate’s Wife,” for example (including Sharon Salinger’s Taverns and Drinking in Early America) happened after I’d come up with the basic idea. On the other hand, when I wrote “The Priest’s Wife,” set in tenth-century England, I drew on long years of interest in religion in general, including early and medieval Christianity, as well as feminist theory and history. Still, I read or re-read some general histories of medieval Christianity and medieval European women, and was lucky enough to find some specialized books on married priests and their wives, the most useful and relevant being Anne Llewellyn Barstow’s Married Priests and the Reforming Papacy: The Eleventh-Century Debates. I also found informative sources about Anglo-Saxon architecture and about the ordinary lives of people at the time: the crops they grew, the furniture and clothing they used, what they ate and drank, what holidays they celebrated. Here’s a partial list:

- Lisa M. Bitel, Women in Early Medieval Europe, 400-1100.

- Martha Carlin and Joel T. Rosenthal, eds., Food and Eating in Medieval Europe.

- Michael Frassetto, ed., Medieval Purity and Piety: Essays on Medieval Clerical Celibacy and Religious Reform.

- Bridget Ann Henisch, The Medieval Calendar Year.

- Susan A. Keefe, Water and the Word: Baptism and the Education of the Clergy in the Carolingian Empire.

- Clare A. Lees and Gillian R. Overing, Double Agents: Women and Clerical Culture in Anglo-Saxon England.

- Alan Thacker and Richard Sharpe, eds., Local Saints and Local Churches in the Early Medieval West.

- Diana Webb, Medieval European Pilgrimage, 700-1500.

This may seem like a lot of books (and it’s only a partial list). We fiction writers often do research and then end up with way more information than we can use. But there’s always the option of applying old research to new writing projects. The novel I’ve just finished features a female Roman Catholic priest who is a scholar of — surprise, surprise — medieval Christianity.

But for that project, I ended up reading even more books.

+++