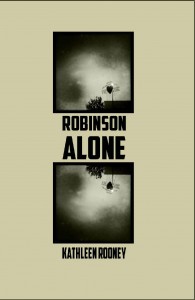

Our Research Notes series invites authors to describe their research for a recent book, with “research” defined as broadly as they like. This week, Kathleen Rooney introduces us to Robinson Alone, her novel in poems recently published by Gold Wake Press.

+

My husband and fellow writer Martin Seay has a not particularly rigorously followed rule that he won’t read anything by anybody who wrote more than ten books — “because they have nothing to say. They’re just recycling material out of greed or some compulsion.”

My husband and fellow writer Martin Seay has a not particularly rigorously followed rule that he won’t read anything by anybody who wrote more than ten books — “because they have nothing to say. They’re just recycling material out of greed or some compulsion.”

Lucky for me, I fell in love with and based my latest book, the novel in poems Robinson Alone, on Weldon Kees, a minor literary figure with only three books of poetry, one story collection and one novel to his name. Equally lucky for me is that these books are all killer, no filler, so I was able to have more than enough material to contemplate and work with over the course of the ten years of on and off research, writing, and revising I did to complete the project.

It should be noted that part of the reason Kees’ literary output was relatively small is because his interests and talents were so wide ranging — he did admirable work in photography, was an Abstract Expressionist painter who showed in New York alongside such luminaries as Clyfford Still and Willem de Kooning, he dabbled in experimental film and recorded an album of jazz and blues songs — and because he disappeared forever at 44 years old.

Also, owing to his short and underappreciated life and oeuvre, the body of secondary material — writing on Kees and his writing — is relatively scant as well, but what there is is very good, particularly Vanished Act: The Life and Art of Weldon Kees, the 2003 biography by James Reidel. Also indispensable to me were Kees’ collected letters, published as Weldon Kees and the Midcentury Generation in 1986 by Robert E. Knoll; I was able to use lines from this book to create the 15 centos included in Robinson Alone.

In actual life, I saw the Kees archives at the University of Nebraska in Lincoln — it did not take long. And I went to New York City one winter and visited — or tried to visit; there was one I couldn’t find — all ten of the apartments he lived in when he was living there, before he left for the West Coast to try to start over. And of course I read a great deal about the 1930s, 40s and 50s and strove for the utmost historical accuracy.

But mostly I tried to access Kees by means of imaginative sympathy. It is easy to become not just an admirer of but an evangelist for a figure like Kees because he is so clearly brilliant and so clearly unjustly marginal. I hope that when people finish Robinson Alone, they are left with the feeling of wanting get their hands on everything that Kees himself produced.

+++