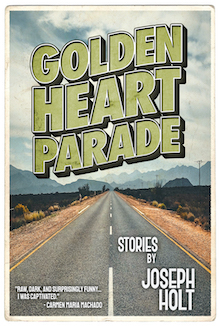

Our Research Notes series invites authors to describe their process for a recent book, with “research” defined as broadly as they like. This week, Joseph Holt writes about Golden Heart Parade from Santa Fe Writers Project.

+

We all want to write novels. Novels, we think, are the greatest form of literary achievement. They’re ambitious, they’re complex, they explore themes that sustain readers over hundreds of pages. If we’re lucky, our novels will outlast even us. Yet we have far more ideas for novels than we have actual novels on bookshelves. They’re out there in the ether, half-formed ideas spoken lowly to friends, half-finished files now moldering on our hard drives. That’s just a guess, of course. And I’m saying we, but I mean I. I had an idea for a novel I couldn’t finish.

We all want to write novels. Novels, we think, are the greatest form of literary achievement. They’re ambitious, they’re complex, they explore themes that sustain readers over hundreds of pages. If we’re lucky, our novels will outlast even us. Yet we have far more ideas for novels than we have actual novels on bookshelves. They’re out there in the ether, half-formed ideas spoken lowly to friends, half-finished files now moldering on our hard drives. That’s just a guess, of course. And I’m saying we, but I mean I. I had an idea for a novel I couldn’t finish.

About twelve years ago now, I began a novel to be called Make It Yours, which would be set among the farmland and rural roads in my home state of South Dakota. In it, a highway worker named LaPointe would spy into a married couple’s home — eavesdropping, so to speak, as they converse by sign language. The mystery of their communication would drive him to obsession. Meanwhile, the other guys on his highway crew would have their own problems: debt, drinking, and divorce. It was going to be a tragic novel. At least one man would die, and the others would face down their own limitations. I wanted to say something about bridges, the ways we connect and fail to connect, and I figured this highway team would work on literal bridges.

Well, I was unprepared to write that novel. What were these men doing all day at the side of the road? Drinking store-brand cola and picking their asses? I didn’t know what trucks they drove, the names of their tools, their idle thoughts when the work abates and all you hear is the prairie wind. But I had resources. My cousin Jordan worked for the state Department of Transportation, and I interviewed him at length. My brother-in-law Shaun had an SLR camera, and we took hundreds of photos of the local rivers, roads, and bridges. Yet the more research I did, the more I stalled in my writing. I wasn’t up to the creative task.

I turned thirty around this time, and my life wasn’t what I wanted it to be. I was new to sobriety, irrationally anxious, fumbling in my relationships. I had a good job — adjuncting at the University of Minnesota — yet I was deeply unhappy. My life had no rhythm. Add to that, I felt like a failure to have stalled on this novel. Maybe if I finished it, I thought, I would redeem myself and set my life down a more productive path. But how?

In hindsight, I should have raised the white flag, either quitting the project or admitting I needed help with my writing. But no, that would have been too sensible. Instead, using my cousin Jordan as a reference, I got hired on a seasonal bridge crew with the South Dakota DOT. This true-life experience, I believed, would lead me to write with authority, and thus I cleared out of Minneapolis and returned home to live in my parents’ basement.

What fun, truly, working on those highway bridges. We were a crew of four: Todd, our concrete man who was so lean that no belt could hold up his pants; Dennis, our utility guy who could fall asleep in the truck given any lull; Quincy, the natural mechanic who was youngest and cockiest of us all; and then me, the rookie dope better at crosswords than at balancing a wheelbarrow. The four of us, we spent more time together than we did with our own families. Todd, Dennis, and Quincy paid me the greatest favor, which was to tolerate me and allow me to improve.

We touched a number of bridges in the upper eastern corner of South Dakota, cleaning the decks, rebuilding guardrails, constructing berms to prevent erosion. But more than anything, we patched rotten concrete, which can threaten a bridge’s structural integrity. That meant setting barrels and closing off a lane of traffic, sawing, jackhammering, and sandblasting, then pouring new concrete into the roadbed. It was tangible, satisfying work. We could see our progress. And me too — I could see my own progress. I was waking up early, working outside in the sun, accepting my small role on the crew.

I worked two summers in that job. During the off-season, I remained in my hometown and taught online. I got my own apartment and rented an office near the library, rode my bike and made new friends, quit the cigarettes, began eating healthier, I even volunteered as a youth basketball coach. My attitude improved — greatly. Did it lead to a novel? Hell no. It led to something better: gratitude, joy, and renewal.

And then a few years passed. I moved down to Hattiesburg, Mississippi, for graduate school. By then I had long abandoned Make It Yours as a novel, having compiled maybe 75 pages of notes and snippets, but never a continuous narrative. One week I had a story due for workshop, but few ideas, so I returned to LaPointe and his fictional highway crew. At the time I was fascinated with frame narratives, so that’s the form my story took. Toward the end, on a whim, I extended the frame conceit and introduced myself as the narrative architect, explaining my failed efforts in trying to tell the story first time around. It went over well in workshop, and the next year “Make it Yours,” now a 4,500-word story, received an AWP Intro Journals Award.

“Make It Yours” is now part of my debut collection, Golden Heart Parade. To write it, I had to learn everything and forget it, then make it up anew. I researched for months and years only to pour out the story in a single week. (I did, of course, edit and revise the story afterward.) And in the end, the technical aspects of bridge maintenance remain largely peripheral. So what was all that road work for? To be sure, it benefited my spirit more than it benefited the story.

And my time on the road crew informed other stories in Golden Heart Parade. One night at the Applebee’s in Brookings, SD, my co-worker Todd convinced two tourists to accompany us to a townie bar and see the local color — an encounter that became the karaoke story “Sing Along.” Later on, Todd told me how he’d returned home one night to find a passed-out-drunk man on his kitchen floor, which I reimagined for the story “Worst at Night.” And in “Charges,” a thirty-year-old man leaves the big city and invents a job for himself outdoors, much as I had myself.

For some artists, research means going to the library — or, more likely, going online. But for me, that only leads to distraction. I’m better off observing the world around me, noticing images, scents, textures, my own emotions in a given moment. I might take notes, brief notes, if it helps me remember. But by now I’ve learned that you only need to sit still and trust in what you already know. You don’t need an engineering degree to write about human connection, nor do you need a medical license to examine the contours of the human heart.

+++