Our Research Notes series invites authors to describe their process for a recent book, with “research” defined as broadly as they like. This week, Kirstin Allio writes about Clothed, Female Figure from Dzanc Books.

+

There’s a braided relationship between mother-in-law and daughter-in-law; the marriage is the third strand. Three-part harmony, unity, or multivalent discord. The day after our wedding, my husband and I moved into a rambling old house that, at first, commanded and defined us. Circa 1850, it held forth at the top of a treacherously steep flight of odd-angled granite stairs on a mongrel block in historic Providence. A multitude of bedrooms were painted old lady bathroom blue; there was a thick dermis of orange-brown basketweave wallpaper, a humpbacked attic, and a moist basement with an antique dirt floor.

There’s a braided relationship between mother-in-law and daughter-in-law; the marriage is the third strand. Three-part harmony, unity, or multivalent discord. The day after our wedding, my husband and I moved into a rambling old house that, at first, commanded and defined us. Circa 1850, it held forth at the top of a treacherously steep flight of odd-angled granite stairs on a mongrel block in historic Providence. A multitude of bedrooms were painted old lady bathroom blue; there was a thick dermis of orange-brown basketweave wallpaper, a humpbacked attic, and a moist basement with an antique dirt floor.

At the same time, my new in-laws, from across the country, were downsizing, and rapidly closing in on us. In advance of their arrival (a grandchild was imminent), they sent sheet sets and bed-skirts and several hundred towels in super-saturated, Southwestern hues. Or so it seemed to me — hallucinating while pregnant.

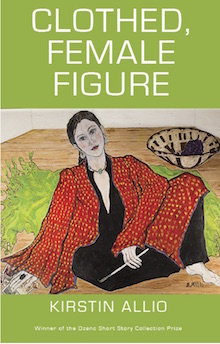

There was also a life-size self portrait of my mother-in-law, who was a brilliant amateur painter, and also the most beautiful woman I had ever known. Even now, remembering it, I pause for air.

The other day I was heading into an office-supply superstore, distracted, all harried housewife and beached mother of teenage boys, when I collided with a figure in full black hijab, slits for eyes. I stifled a cry, pure alarm, and recoiled, hot-cold with toxins. A woman protected from men’s eyes, or cladding to protect men from themselves? The hood seemed sinister to me, a menacing disguise. The figure collected itself. Then as she hurried past, I heard a disembodied voice, Sorry I scared you. Just a regular American female like me.

I was walking on my parents’ road in Maine this morning, where people park their pickup trucks facing out, and I ran into a neighbor, a clear-eyed older woman wearing a purple bandana, headdress against the scourge of green-head flies. We had only met once before, but at 6 a.m., a lonely hour, we were inclined toward company, and she rushed right in. What do you write? A question I still haven’t figured out how not to kill. Fiction? Essays with their own meandering path? I could hear the static, spotty reception in my own head. The road curved through dense, moosey forest, nubs of wild raspberries velveting in the road-edge sun. I didn’t want to say I write about women’s lives. But there we were, the real thing, a scene I’ll use.

A braided relationship between mother-in-law and daughter-in-law that’s stronger than the sum of its strands. My mother-in-law’s enormous self-portrait has weathered several more moves, other old houses, and it’s no longer threatening, but tells a part of my story too. She sits barefoot on the ground, clothed in red and black, her stage set with basket and grapes, paintbrush and green shawl, wearing her signature braid. Her left hand rests on snippets, a collage of family photographs, and the image suggests to me degrees of vulnerability and pride, objectification and self-knowledge. She’s 83 now, and I’m 41, fast approaching the age she was when, coming to terms with the fullness of herself as a mother of three grown sons and one not-quite-still-little boy, (my husband), she began her self-portrait.

Some time after I found out my story collection would be published, I was looking at my mother-in-law’s painting, maybe practicing returning the gaze. Suddenly I thought that all along it had been a guide. I had been invited to enter it. In trying to understand how my mother-in-law saw herself — in art — I’d stumbled into my own art, tracking, braiding women’s lives. I saw how the painting unified the stories I’d put together, and I realized that the title of my collection, Clothed, Female Figure, described the unnamed painting too.

Some time after I found out my story collection would be published, I was looking at my mother-in-law’s painting, maybe practicing returning the gaze. Suddenly I thought that all along it had been a guide. I had been invited to enter it. In trying to understand how my mother-in-law saw herself — in art — I’d stumbled into my own art, tracking, braiding women’s lives. I saw how the painting unified the stories I’d put together, and I realized that the title of my collection, Clothed, Female Figure, described the unnamed painting too.

There’s an anticlimax here that I can’t work around. An author probably never gets the book cover she wants. But it doesn’t change the ending. I didn’t know until I asked her if I could borrow it for the cover of my book that my mother-in-law felt she never finished her self-portrait.

+++