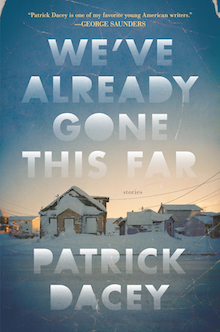

Photo: Tara DaceyPatrick Dacey grew up on Cape Cod and went to Syracuse University hoping to become a professional football player, an offensive lineman to be specific. Because of an injury, he was unable to pursue a collegiate football career, and after taking a class with George Saunders, he was inspired to be a fiction writer instead. His stories have a similar range of possibility: former athletes and car salesmen and housewives and reality television stars in daily suburban life or on the road or surveying a destroyed, war-torn town in search of a dog. We’ve Already Gone This Far (Henry Holt & Co., 2016) is centered around the inhabitants of Wequaquet, Massachusetts, “a town like many towns in America, a place where love and pride are closely twinned and dangerously deployed.” The shadows of a hopeful past and the Iraq war permeate everything. A former teacher, reporter, and landscaper, Dacey finished the initial draft of these stories while working overnight at a homeless shelter and detox center. The collection has been called “intelligent, deeply felt” by Mary Gaitskill, while Dacey’s mentor George Saunders called the collection, “dangerous, funny, sometimes savage…a terrifyingly dark view of America, as well as a movingly optimistic one.” Booklist noted that, “We’ve Already Gone This Far illuminates both the quotidian details and the profound strangeness of modern American life.” The collection was also named one of Brooklyn Magazine’s 101 Books to Read in 2016. His novel, The Outer Cape, is due to be released in May 2017. Dacey currently lives in Richmond, Virginia, where he teaches creative writing at the College of William and Mary, and is working on two new novels, a short story collection, and a set of television scripts.

Dacey talked to Necessary Fiction about his story collection, his forthcoming novel, the ways in which stories surprise us, the struggles all writers face, and how the question of “What if?” inspires creativity.

+

What was your writing process while working on this collection? I’ve read that you composed the stories while working the night shift at a homeless shelter and detox center. Are there ways you put yourself mentally into Wequaquet in order to maintain the rules of this universe while working in a distinctly different one?

Some of them were composed there. Mostly, I finished the book and revisions while on the graveyard shift, listening to men snore and break wind and talk in their sleep. I’m always working, no matter where I am, so, sure, there were times I wrote then, but I usually get in touch with these worlds when I’m called to. That might sound odd, but I don’t come from a background in literature, and my family has worked in construction, insurance, and for various state agencies, so I feel that there’s some other thing, greater than myself, that delivers a thought, a beginning of a story, a character, and for a long time I didn’t know why, until I finally gave in, and saw that thing for what it was, a source. So I owe it to that source to be open to the strange, odd, uncensored material that’s passed down and through me.

Some of them were composed there. Mostly, I finished the book and revisions while on the graveyard shift, listening to men snore and break wind and talk in their sleep. I’m always working, no matter where I am, so, sure, there were times I wrote then, but I usually get in touch with these worlds when I’m called to. That might sound odd, but I don’t come from a background in literature, and my family has worked in construction, insurance, and for various state agencies, so I feel that there’s some other thing, greater than myself, that delivers a thought, a beginning of a story, a character, and for a long time I didn’t know why, until I finally gave in, and saw that thing for what it was, a source. So I owe it to that source to be open to the strange, odd, uncensored material that’s passed down and through me.

The story collection feels very male in its perspective in some ways and yet you are very accomplished when writing a female POV, for example Donna Baker, whose son is deployed and whose husband seems to be losing interest. You tackle a lot of issues, family, parenthood, love, that sometimes get relegated to women’s fiction in a very literary, razor sharp way. What is your goal when writing from the perspective of someone quite different from yourself, either because of gender or race or circumstances?

This is a good question. There are certain human emotions we all share, but I had to be careful not to pretend as though I know certain things about women I could never know. I took a lot from watching my mother struggle with depression, divorce, and wanting to be loved and respected for all the good she did in her life. She was beautiful and died young, and she was an artist, but gave up any desire to return to her work when she had to raise my brother and me. What I do is take all that goodness and add the way I’d probably feel about this, which is bitter, and then touch that up with a dark sense of humor that probably comes from being observant and open to my surroundings, and some personal damage. So, then you get the narrator in the first story. She’s bitter. She sees Donna Baker as absent-minded and ignorant, the way we see our neighbors and acquaintances in these two-trait ways. That led me to want to write from Donna Baker’s point of view. So then we get the full portrait of her pain and struggle.

I would love if there was no such thing as women’s fiction or underrepresented writers. I don’t feel I had much of an advantage being a white male. It took eight years and 247 rejections from agents and publishers to get this book. I got divorced, worked general labor to support my infant son, lived in motels and furnished rooms. So, I paid my dues. But I do see a lack of diversity, and it’s disappointing, and I think it’s because publishers aren’t willing to let first time writers get away with too much for risk of losing money. I feel fortunate to have a great team at Holt. I mean, they let me include a story in the collection that’s an eight-page single sentence.

Speaking of “Ballad,” an eight page sentence, you play with tense, POV, even punctuation in this collection. Do you view form as a way either to shape what you are trying to accomplish or to underscore what you are trying to say?

To be honest, I don’t think much about it. The story starts out in the way I hear the first line in my head. Most of the time the story is confessional, so the first person works. But, for instance, with my forthcoming novel, The Outer Cape, I heard each character’s story being told to me, so they ended up in third person. Most of the stylistic choices are really just gut choices. “Ballad” gets most of the attention because it has no punctuation, but really I was trying to get down on the page a broke father’s worried train of thought. In “Frieda, Years Later,” Leonard is trying to read a book in print, Confederate Love Songs, while his wife is reading from her tablet. The text is missing letters and words from the glare off the tablet. This, to me, is riskier, because the text, or absence of text, could distract from the purpose of the scene, which is to show distance between two people, one going forward, the other back.

There is a big difference in how the children view the world and how the adults do in this collection, as in life. Children have optimism and a plucky quality that has been lost to the older citizens of Wequaquet.

What I’ve been working most of all with in my writing is the idea of love. To me, happiness, sadness, jealousy, rage, amazement, these are fleeting abstract emotions. But love is poised to exist in us at all times, as is hate. I don’t know if you can have one without the other. You love the earth; you hate the people who destroy it, and so on. But, the main thing here is that children, infants especially, they love everything. Even more so when they feel love. I think that’s the main conflict in all these stories, and in life, this idea that we not only want to be loved, but we want to feel that same love we once did when we were kids, that joy of discovery, rain snow sun cherry-flavored popsicles impromptu dance parties the thrill of being found and tagged, “you’re it!”

In your story, “Downhill,” the narrator’s son Jasper is born blind, so he tells his son fantastical versions of the world. The opening paragraph begins with the father explaining the world in clever, creative ways, before the reader knows Jasper is blind, and it comes across as any parent trying to paint a better world for his or her child. When it is revealed in the second paragraph that Jasper is blind, it is very effective, and then the mother scolds the father for his rosy stories that will surely be dispelled by reality one day. This seems in keeping with a theme of the book that childhood can be an idyllic place that adulthood and actuality sullies. Do you think this is always true?

“Downhill” is one of my favorite stories in the collection. The entire story is based on misperceptions. The father wants to be concerned with innocents starving in North Korea, and people getting their heads chopped off in Juarez, Mexico, but he has to sell cars to pay for his son’s corneal eye transplant, and so, he can’t possibly worry about all this stuff looming over him or else he’ll end up like his boss, Big Tim, who is slowly losing his mind as he lets the ever-depressing news infect his daily thoughts. So, no, I don’t think adulthood sullies dreams of an idyllic future. But one’s idealism often runs into one’s panic and pessimism, and, in this country, who trusts an idealist anymore? I think the characters in these stories are doing their best because, inherently, they want to be someone’s hero, mainly their children’s.

You are a relatively new parent, as am I, and parenthood is a strong, reoccurring theme in the collection. I imagine some of these stories were written before your son’s birth, and others after, and all edited or revised with the eye of a parent. How has that role changed you as a writer?

I think it changes everything. Most of all it changes your idea of what love is, which I think changes your work, because, suddenly, everything is on the line. So, in revising, I economized my prose, made sure everyone had something at stake and the consequences of their decisions were immense. Because that’s what it feels like to be a father.

There is a building feeling of dramatic irony as the collection progresses because we know information about these characters before they get their own POV, for example the first story tells us about Justin’s fate so that whenever he appears, we know things about him that he does not yet know. How did you choose the order of the stories?

In that way. I wrote a version of “Patriots” in 2008. Then I wrote two shitty novels and twenty shitty short stories, before I returned to “Patriots” in 2012, and read it and laughed, and I thought, if I still think this is funny and powerful, then maybe there’s more here. What I noticed was that I introduced all these other characters, and I could see, maybe not a novel, but a larger story of a place and time. From there, I knew I wanted Justin, his friends, neighbors, parents, and the town itself, to play their own roles in the story of this time, of economic insecurity, war on terror or terror war or plain old terror, and American zeal. By the end, it’s inevitable that we hear from Justin, but though we know the outcome, we are still surprised, in the way that stories of the past always surprise us in the present, and are told and retold, rearranged and embellished. History is fiction. That’s why storytellers will always be needed, and, hopefully, revered.

As a reader, by the time we get to Donna Baker’s letters to her son in “Incoming Mail”, we know things she does not, and so her letters are not at as light hearted to the reader as they are to her. Was that a goal in your writing?

That was the goal in positioning the stories. I don’t know why, I feel I had to be hard on myself in order to make this book unique. So, that story in multiple letters works in two distinct ways: the one you pointed out, and the fact that we aren’t reading her son’s responses, yet we still feel a tension, conflict, some movement towards an ending. We know Donna will be changed in one way, but we see then she has changed in another way.

Despite being set in a relatively small, suburban town where lives and fates overlap frequently and are inexorably intertwined, there is a strong sense of alienation or sometimes friction within the community. How do you see tension between neighbors as an inherent element of contemporary society, which is a negative, but also as a positive for creating dramatic tension in a story?

The alienation is right on. That’s what’s strange about small towns or communities, where we’re living so close to each other, know each others’ faces, and even read about each other in the local papers. Yet, we barely or rarely speak to one another, and when we do, it’s as if we somehow know we won’t have this opportunity again, and whatever meanness of thought we had towards this other person disappears and we go blank and are now open to hearing whatever the other has to say, even if it is undeniably idiotic, and we will save those thoughts for ourselves, later, for an IM or Facebook post or just let it build inside until the next interaction with someone, when we let it all fly about what this person said someone else said. This is why it sometimes feels, to me anyway, that people are talking much faster these days, and everyone is distracted by a buzz or beep or ringtone…better get to the point quick. Facetime is being rationed.

There is a juxtaposition between young and hopeful or even manipulative love in this collection, for example “To Feel Again,” with the mature realities of characters who have reached a very mundane, chipped place in their relationships, but have not fully given up on it yet. Do you view this sort of ennui as inevitable in relationships and in adult life, or is it a consequence of being from this place, of living in Wequaquet?

I’m not sure the place has so much to do with it, but of course, long winters start to shadow the soul seeking promise. It’s more that we have these burdens, and we collect them over time, and most of them have to do with other people we’ve brought into our world, and so our world has gotten bigger and we have no time for this other, larger world of national and international agencies attempting to direct us to think about this issue or that, pay attention, insult you for not paying attention, on top of that, start thinking about how we’re running out of water, the planet’s on fire, and maybe our only hope is to live in domes on the moon or just go extinct, and then what will our names and histories matter?

There is a biting, edgy humor your characters express, for example the narrator of the first story refrains from saying what she really thinks to a mother who fears “those hoodlums are back” and who doesn’t imagine her neighbor reflects about the mother’s deployed child, “I thought to say we haven’t had any criminal activities around here since your son, you know but I didn’t.” How do you balance humor and darkness when writing? Does some of the humor come out naturally as you write or do you strive to put it in there or both?

The humor, or dark humor, comes naturally. I’m a bit obsessive compulsive; I have these thoughts, as in, “what if?” which is the question all writers need to constantly be asking themselves. Because, what if I steal this baby formula for my son and get caught and have to spend a week in county and make friends with some other poor souls and we start a men’s group and charge a fee to join and get so big we open a compound in Costa Rica and we’re rich and stress free but missing something, missing the struggle, the need to steal baby formula, and we get angry and blow up the compound and are worse off than before, back to our basic instincts, our needing baby formula instincts. What if opens all doors, creates possibility and consequence. And so, to be unfiltered in your thinking and observations, you balance the light and the dark.

In “Friend of Mine,” Mac declares, “I don’t know when I stopped wanting to be a fireman…It’s just that I don’t care so much anymore about saving lives, considering there’re so many pieces of shit to be saved, and this someone goes on to do something completely fucked up, and you have to live with the guilt that you were the one who kept him in the world when it was all set for him to burn” (p. 44). How does lost hope and a lack of opportunity and a reality that some things are not worth saving define the fate of these characters?

Well I don’t really consider hope at all, it’s a projected future, and most of these characters are dealing with the aftereffects of their pasts, which informs their ultimate fates, or their fates in these stories. I think of that line as taking a thought two beats further, and so what was really a justification for why he didn’t do what he wanted to as a kid, becomes something both savage and funny, and very real.

“I’ve been waiting for the day when everything will change, thinking yesterday was the day before this day, which is the day I’ve been waiting for” (p.45). How is the idea of the day, or event, or the moment one has been waiting for important within a story in terms of creating drama and tension?

My father said that to me once. I think it helps you look back on when you suffered most, and how that can all change in an instant. The day before the day everything changes. That’s the most important day, because that’s the struggle, the drama, the tension. The thing itself, the final happening, say, the battle at the end of an action flick, is never as interesting as the course taken to get there.

Having someone you respect as much as George Saunders support you and believe in your writing at such an early stage must have felt huge. Could you talk a bit about the importance of mentors in writing? How does the role of a mentor change over time for you?

George has been supporting me since I was an undergraduate at Syracuse University. I wrote my first story for his class, when I didn’t know who he was, hadn’t read but five novels required in high school, and only took creative writing because I thought it would be easy and could check off one of my electives needed to graduate. He said he thought I had something, and because of that, I started to work on this thing I might have, mainly because I didn’t have much else going on. When I graduated, he recommended I take a few years off and then apply to the MFA program. I did a lot of drinking and traveling and working, and came back sober and with some savings, and felt lucky. In graduate school, I just wanted to get better. I didn’t learn how to write or find my voice or whatever people who criticize MFA programs think goes on there. I read, I practiced, and I listened. In that way, I developed a discipline and work ethic to become a writer at all costs. That’s what George did when he was young, and that’s what most writers do, I think. They give most, if not all, of themselves to the craft. So, I’m not sure any working writer can be a mentor; that’s not the writer’s place. I learned from George and from Arthur Flowers, Mary Karr, Mary Gaitskill, Michael Burkard, Chris Kennedy, that writing takes discipline, long hours, spells of depression and insanity, anger and extreme joy. Syracuse was and is a special place in that way. Everyone is at work, and so the community feels like an equal playing field, no matter the level of success certain writers have — we’re all struggling to get better.

What authors are you reading now? How is that selection different from when you were younger or in graduate school?

I feel fortunate to have not studied English in college or to have had any interest in literature or books without pictures. Because of that, when I finally became addicted to the craft, the novel and story, I had a chance to read all of these books I should have read when I was much younger, with a keener sense of awareness, and time. So, I read Steinbeck, Hemingway, Morrison, Bellow, Nabokov, Chekov, Cheever, Carver, Welty, Faulkner, Marquez, read most of the famous works of literature in my mid to late twenties, and now in my thirties, continue to read and re-read some of those books, as well as contemporary work that comes recommended, or that I take a chance on, wanting to support debut writers, conjure good karma. I’ll read Under the Volcano, Autobiography of my Mother, Revolutionary Road, Jesus’ Son and The Sheltering Sky every year, just for the cadence of the prose, and because time is handled so well that I learn from those books each time I read them. I tend to have a book I’m rereading, along with a new novel, and a book of short stories. At the moment I’m rereading Lolita, reading A.M. Homes’ May We Be Forgiven, and Joy Williams’ _The Visiting Privilege.

Do you have any particular habits or writing exercises you use to get back to work when you are distracted or not feeling motivated?

No. I’m not easily distracted because I don’t want much. I take care of my son, exercise, and write. That’s about it. I wake up around four in the morning. I sit in a chair. I write. Whether it’s good or bad, that discipline is essential for me. When I’m not writing, I’m thinking about characters, putting them in situations, trying to figure out time and place. Time and Place, those are the toughest things for a writer to work through, especially in a novel. Not only are you moving forward, becoming a better writer, you’re also dealing with your own past, thoughts, dreams, etc., and you then have to be willing to deal with a host of other people’s pasts, thoughts, and dreams. It gets tangled. You untangle. You re-tangle. You give up. Then you admonish yourself for giving up. Then you begin again. Always a piece of you is cut out in the process. If it’s not, then what’s on the page probably isn’t very good. I recently finished a story called, “Say Goodbye,” and that story took a whole lot from me. I think it’s my best work so far. At this point, I’m working towards five books, two collections of stories, and three novels. All of them books I give myself over to, and that I’m proud of, and that I can read as though I did not write them, and be entertained. I’m two down now, with three to go. Maybe I’ll want more, but maybe I won’t have anything more to give.

Your forthcoming novel, tentatively titled The Outer Cape, was pitched as being in the tradition of “Franzen, Ford, and Banks, and centered around a weekend in a summer cottage on the Northeast cape, reflecting back at us what the American family is becoming.” How do you see writing as a tool to address where we are as a society? Who we are as people?

The novel has definitely changed a great deal since that initial pitch. I had to go back through each character’s story to get them to this present of uncertainty. So the novel actually spans four decades, and we see each member of this New England family from each others’ point of view, as protagonists and antagonists, heroes and villains, murky, unreliable, well-meaning human beings. I can only address where I am in society. I try not to pretend that I know what it’s like to be black and see my children shot by police, or gay and be told I can’t eat in a restaurant. I can’t know these injustices or imagine them. What I do know is for a while now this country seems to be set for a riot. I guess the thing that finally cracks us open will be something so miniscule, like an infant tapping a giant, cracked boulder with a tiny hammer. I guess this because we can’t even get gun laws changed after children are shot in the face.

+++

+