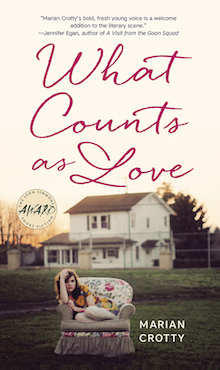

Marian Crotty’s debut short story collection What Counts as Love was published by the University of Iowa Press as the winner of its 2017 John Simmons Short Fiction Award. The ten stories in this collection take place in self-healing houses, rehab facilities, expatriate communities in the United Arab Emirates and various unexpected locales. Featuring mostly women protagonists, the stories are threaded together by the desperation that characterizes the different women whose attempts at self-determination and self-expression are met with resistance. Marian Crotty talked to Necessary Fiction about the development of her collection, and the significance of class and place in her writing.

Marian Crotty’s debut short story collection What Counts as Love was published by the University of Iowa Press as the winner of its 2017 John Simmons Short Fiction Award. The ten stories in this collection take place in self-healing houses, rehab facilities, expatriate communities in the United Arab Emirates and various unexpected locales. Featuring mostly women protagonists, the stories are threaded together by the desperation that characterizes the different women whose attempts at self-determination and self-expression are met with resistance. Marian Crotty talked to Necessary Fiction about the development of her collection, and the significance of class and place in her writing.

Congratulations on winning the John Simmons Award, no small feat. Please describe the origin story of your collection. What was the process of completing a collection like for you? How did it come together and evolve? Were there any stories that were previously included and didn’t make the cut or any which were added after the collection’s acceptance for publication?

Thanks, Amina. I was writing for a pretty long time before I thought seriously about trying to put together a collection. I was working on stories consistently but viewing each story as its own singular project — a chance to investigate a person or situation I’d been thinking about or to try out something new technically. After I had about ten stories that I felt pretty good about, I looked for thematic connections and found that many of the stories dealt with some kind of partially satisfying relationship. Then I wrote “Kindness” specifically for the collection. One story about a college student working at a strip club got cut before I sent it out and “The Next Thing that Happens” replaced it. Once the collection was accepted for publication, I wasn’t allowed to add or subtract any stories. The press explained that it wanted to publish exactly what the outside judge had chosen.

Any pearls of wisdom for other writers working on their first collections?

I think the best collections have stories that are connected thematically without any of the characters or situations blurring together. Your recent collection The Loss of All Lost Things is a great example. I also appreciate this about Mia Alvar’s In the Country. I think a lot of writers tend to worry a little too much about the connections between stories and not quite enough about making each of the stories distinct. One piece of practical advice, especially if submitting to a contest — make sure the first three stories are strong and also representative of the collection as a whole. I would also caution against assuming the stories that wound up in the most prestigious literary journals are your best stories.

I think the best collections have stories that are connected thematically without any of the characters or situations blurring together. Your recent collection The Loss of All Lost Things is a great example. I also appreciate this about Mia Alvar’s In the Country. I think a lot of writers tend to worry a little too much about the connections between stories and not quite enough about making each of the stories distinct. One piece of practical advice, especially if submitting to a contest — make sure the first three stories are strong and also representative of the collection as a whole. I would also caution against assuming the stories that wound up in the most prestigious literary journals are your best stories.

The stories in your collection take place in a variety of locations, from Arizona to the United Arab Emirates, from rehabilitation facilities to college campuses. What is the significance of place or locus to your stories? What goes into your decision to decide when and where a story will take place?

Place is huge for me and almost always there right from the start. Place is what the helps me get into the fictional dream world each time I sit down to write as well as a tool that helps me brainstorm. When I get stuck, I ask myself, “What would be likely to happen in this place? What are the unspoken codes here? How do people move and talk and interact here? Who else might be there that can interrupt this moment and make trouble for the protagonist?” The time period and its politics and concerns are something I tend to interrogate more in revision.

Where do your characters come from? How did the characters for this collection come about?

I usually start with the place and the situation and then the character comes closely after that — often a person who I imagine being challenged by the situation. The central characters in this collection are all a combination of research, imagination, and personal experience. A few minor details — such as the F.B.G.M. tattoo in “A Real Marriage” — are lifted directly from real people.

The “House Always Wins” stands out as the only story in your collection narrated solely by a male character (“Kindness” features alternating narrators), as well as the only story to veer away from the strictly realistic worlds we see in order to delve into the speculative realm with your depiction of the unique phoenix-like Forever Homes. How do you envision this story fitting in with the collection’s internal logic and structure?

This is a story that I went back and forth about including for the reasons you mention — male narrator, fantastical elements. It’s definitely an outlier. The argument for keeping it was wanting to include a story that examined a hook up relationship and wanting each of the stories to feature worlds and characters that were different from each other in memorable ways.

The women in your stories are judged pretty harshly by others and their attempts to self-define clash with the expectations others have of them. This is true whether the relationships being depicted are romantic or familial. A mother can’t see her daughter as anything other than an addict and her daughter can’t see her as anything other than overbearing; adolescent girl voyeurs project onto the young woman they watch; a victim of domestic abuse is seen as a trouble-maker; and a lesbian comfortable in her own skin and body is viewed by a casual sexual partner as “going out of her way to act like a lesbian.” Consequently, many of these women engage in their own processes of self-improvement/self-definition, from enrolling in an eating disorder treatment facility, getting married, training to work a male-dominated field, or moving overseas, to various outcomes. Lurking beneath all of the stories, regardless of theme, is the struggle women face i.e. resisting becoming what others want them to be in favor of honoring the versions of themselves they’ve created. Is this conflict indicative of a larger social commentary at play, and, if so, what does it mean that none of the women in your stories escape facing this conflict?

I think women, particularly young women, are often judged harshly and also taught from a young age to care about other people’s judgments, even if the people are strangers. One of the central conflicts of my twenties was the tension between wanting to develop an authentic self while also wanting to please other people and conform to their expectations. This tension is one that I think many young women are familiar with and was something I wanted to explore in my fiction. I’m not sure that it’s possible to escape other people’s harsh judgments, but I do think it’s possible to learn to ignore these judgments and to stop inviting them into your personal life.

One of the things I most appreciate about your collection is its unflinching look at class and socioeconomic disparities. In your collection we see girls raised by mothers who are housekeepers, addicts, recovering suicides, postal workers, and single parents. We also see women in relationships with engineers, models, youth pastors, construction workers, gas station attendants, and junkies. How much consideration do you give to class background when you create your characters? How do socioeconomic factors impact the way your protagonists understand and respond to love and relationships?

I think about class a lot in my everyday life and, as a result, it often finds its way into my fiction. Socioeconomic factors influence so much about people’s lives — the chances they feel they can risk, the norms within their families and communities, what people feel obligated to give and willing to take. I think for many people these factors play a larger role in their familial relationships than their romantic ones, though class certainly can influence people’s ideas about what a good relationship looks like and when it’s advisable to leave a bad one.

Speaking of which: given your title, I have to ask this question. So, what does count as love?

Well, for me, love counts if you say it counts. What kinds of tradeoffs feel worthwhile really depend on the person and her circumstances at that particular moment in time. These compromises — what feels worth it and why — were what I wanted to investigate in this collection.

+++

+