Veronica looks at Ralfy’s bronze face and sees that beautiful grin, that smile that she really wants to believe exists only for her. It breaks the hardness of his face, and he seems like two boyfriends at once. Since she was thirteen, she’s seen him at all the parties, and even then she wanted to be the girl he invited into hallways to rap to. He entwines his fingers with hers, bites his lip, and presses his forehead against hers, until Veronica has to return his wondrous smile. Despite his bullshit, Veronica is elated Cassandra is here to observe this moment, so that all those people who talk shit can know, can see, he really does love her.

~ “Holyoke, Mass.: An Ethnography”

+

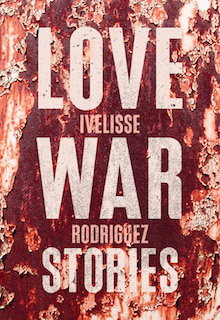

As its title suggests, love is at the center of Ivelisse Rodriguez’s debut short story collection Love War Stories (Feminist Press, 2018). Or, to be more exact, the concept of love is what comes under fire. In nine short stories that take place in Puerto Rico, Holyoke, MA, and New York City, Rodriguez depicts Puerto Rican girls who dream of ideal relationships and perfect loves — and their mothers and aunts who know better. From a young girl dreaming of a perfect quinceañera and the first dance with her escort to an aunt who keeps the love letters sent by the husband who abandoned her, to a tough teen who everyone expects to become pregnant, to a college grad who eats to obscure her identity after breaking up with an abusive boyfriend, these stories reveal the idealized yearnings of young women who have been taught to put their faith in love, while suggesting that love is both a performance and a rite of passage.

As its title suggests, love is at the center of Ivelisse Rodriguez’s debut short story collection Love War Stories (Feminist Press, 2018). Or, to be more exact, the concept of love is what comes under fire. In nine short stories that take place in Puerto Rico, Holyoke, MA, and New York City, Rodriguez depicts Puerto Rican girls who dream of ideal relationships and perfect loves — and their mothers and aunts who know better. From a young girl dreaming of a perfect quinceañera and the first dance with her escort to an aunt who keeps the love letters sent by the husband who abandoned her, to a tough teen who everyone expects to become pregnant, to a college grad who eats to obscure her identity after breaking up with an abusive boyfriend, these stories reveal the idealized yearnings of young women who have been taught to put their faith in love, while suggesting that love is both a performance and a rite of passage.

Necessary Fiction recently spoke with Ivelisse Rodriguez about her short story collection Love War Stories, the concept of love, and the stakes in her fiction.

+

Congrats on the publication of your debut collection! ¡Felicidades! Please tell us about the process of creating your collection. How did you put the collection together? How long did it take for the stories to become a collection? What determined the arrangement of the stories within the collection?

As I was writing the stories, I always thought about them as part of a collection. Never did I see them individually. Some of that probably had to do with being in an MFA program and knowing that I had to write a thesis.

In terms of the arrangement, I wanted the collection to start in Puerto Rico then travel to Western Massachusetts then New York City. Western Massachusetts was the second stop in order to highlight the diasporic journey Puerto Ricans made there and to showcase the lives of Puerto Ricans outside of New York City. I grew up in Holyoke, Massachusetts, which has the highest concentration of Puerto Ricans outside of Puerto Rico, but all the diasporic literature is centered around New York City. So much so that other historical enclaves, like those in Western Mass and Cleveland don’t show up in the literature. So it was supremely important for me to feature the stories of Puerto Ricans in Western Mass.

Besides the location-based element to the arrangement, I also thought about the message of each story’s ending and how they created a narrative trajectory of their own — moving from brokenness (and not necessarily in a bad way) to self-assuredness.

How long did it take for the collection to find a publication home and what was that process like?

It took a long time — I started the first story from the collection, “Love War Stories,” twenty years ago. Over those two decades, I completed an MFA in creative writing and a PhD in English and creative writing, and I was slowly becoming a better writer during this time. I was also submitting and getting rejected but that was because the manuscript was not ready for publication. But sometimes you hear these urban legends from the publishing world where someone gets a book deal with scant written, and you think that can happen to you. But, no, don’t send your work out if it is not ready. It is a waste of everyone’s time.

It took a long time — I started the first story from the collection, “Love War Stories,” twenty years ago. Over those two decades, I completed an MFA in creative writing and a PhD in English and creative writing, and I was slowly becoming a better writer during this time. I was also submitting and getting rejected but that was because the manuscript was not ready for publication. But sometimes you hear these urban legends from the publishing world where someone gets a book deal with scant written, and you think that can happen to you. But, no, don’t send your work out if it is not ready. It is a waste of everyone’s time.

I kept revising and revising the manuscript, and I eventually started placing in contests and/or getting nice rejection letters, so I was finally on the right track. Then I was a finalist for the 2016 Louise Meriwether First Book Prize from the Feminist Press & TAYO Literary Magazine. I didn’t win — the wonderful YZ Chin won for her book Though I Get Home which focuses on characters from Malaysia — but the Feminist Press still wanted to publish my book (so this publishing urban legend came true…).

Do you have any advice for aspiring writers out there working on their debut collections?

I would say that they should know that it is harder to publish a short story collection and that they should also begin working on a novel (if that is one of their goals). Or they should publish the stories individually and not get too attached to getting a book deal for the collection. In other words, don’t let rejection of your short story collection stop you from continuing to write and working on new projects.

I would also tell them that learning to become a writer is not just about writing but also dealing with these emotional aspects that no one talks about in workshop — like the pitfalls of perfectionism or fear of facing the page. I don’t agree with the adage that people have a fear of success. I think people have a fear of failing and that their work isn’t good enough and that they are never going to really get the story out like they want to. And sometimes you don’t. I think that you have to accept that, along with the fact that all your stories are not going to be equally strong, but each story will find its own set of fans.

I also highly suggest that writers learn their writing process. Audience members often ask writers about what his/her/their writing process is. I think this a good question for comparative purposes. Sometimes it is quite stunning to see how different writers write. But ultimately, a writer needs to learn her own process. For example, I learned that starting a new story felt like being at the bottom of a mountain and that then there was always a point where I felt like this story was never going to come together, and then I would have a breakthrough that got me to the end. Learning this about my writing process allowed me to talk myself off the ledge when the story felt hopeless because I knew I had been in this position before and had been able to come out on the other side.

The women in your stories seem to fall into two disparate groups, i.e. younger women who are looking for love and older women who are weary of love. How do these women progress from believing in love stories to antilove stories and how does age affect their outlook on love?

The young women in my stories are like most heterosexual women who have been indoctrinated to believe that love is this thing that will fill them up. It is the one thing in life they are meant to achieve. And they have limited experience with romantic relationships, so they think that the right one (person or relationship) is just around the corner, and their lives will be radically different. While their viewpoint is a bit too idealistic, the young should be hopeful.

And older women should know better. My older female characters can’t really conjure up that idealism one needs at the start of each new relationship because they have been through it. They are hardened to love and love no longer holds the primary spot in their lives like it once did.

The generational clash stems from the older women telling the younger women that their worldview is the truth. For the young women, what the older women think about love is wholly inconceivable. The young think that those unfortunate love stories will certainly not happen to them; though they are already happening to them.

Ultimately, though, both age groups are where they need to be — the older female characters are wiser and have learned from life, and the younger female characters are still dreaming, as they should be.

Many of the stories are about love that has been lost, and about fathers and husbands who are not seen due to death, divorce or abandonment. Although the men seem to be the source of the stories’ central conflicts, we don’t often see them. Even in the stories with younger narrators like “The Belindas” and “Holyoke Mass.: An Ethnography,” the men are often seen from afar. How important are the men to these stories of love?

Men are important to stories of love in that they set them off. They have to show interest in women, they have to say the things women can then repeat to their friends, etc. But in other ways, men are negligible to stories of love because for heterosexual women, their greatest romances are the ones they are carrying on in their heads. Many of the girls and women in my stories are dealing with shady boys and men, yet what is more important for some of these women is the men they have built in their minds. Women will spend hours daydreaming about men, talking about men, inventing a future with men. In a sense, these women are in a relationship of one or in a relationship with a man they have dreamed up, a man who is much better than the man who is physically there (or not there). I wanted to capture this dissonance — this physical absence of men, the ways men disappoint women, but how women hold onto a fantasy (of the man and the relationship) and how much the presence of men in women’s lives exists in the imagination of women.

In “La Hija de Changó,” you have this awesome chiasmic moment where you depict Xaviera, the narrator, interacting with her boyfriend Anthony at the Ritzy party where he is shown to be the outsider, and then you reverse it and have the narrator attend a neighborhood family party with him, where she occupies the outsider position, and I’d love for you to talk a bit about the significance of having your characters navigate disparate cultural spaces and what’s at stake during those various interactions.

In “La Hija de Changó,” Xaviera is a junior at an elite prep school in Manhattan, but she comes from East Harlem, so she straddles two disparate worlds at once. What I wanted to do in this story is capture what so many of us who went to boarding schools or prestigious day schools through scholarship programs or through organizations like ABC or Prep for Prep experienced. Education is normally presented in positive terms, as this great equalizer, but it also brings losses. If you are not coming from a privileged background, elite education cleaves you from where you came from. It is akin to a (im)migratory experience where X land is seen as having streets paved with gold, and when you get there, you realize that your relationship to your homeland will never be the same, that you have to learn a new language, that you are no longer the “norm,” but, rather, you are now starkly different and stand out.

For Xaviera, everything she does — learning about Santeria, trying to stay with Anthony, not dating boys from the Whitney school — is a way to try to hold onto or return to something that is irretrievably lost — lost in the sense that she is now somewhat of an outsider in this space where she once belonged. Xaviera, like so many others, will never be able to get back to the feeling of security that comes from belonging.

In “The Simple Truth,” the narrator dedicates the exhibit to her mother, who is an academic. How does your background as a scholar and an academic inform the stories you want to tell and the way you craft your fiction?

It is important for a writer to be well-versed in her/his/their genre. You need to come to writing knowing the history of the stories you want to tell. It’s a matter of craft. If you want to be a serious writer, then you have to study the conversation you are entering. So as a scholar and a writer, it was important for me to understand the trajectory of Puerto Rican literature from the continental U.S. and to see how I could add to that oeuvre without telling the same story. For my preliminary exams, I studied Latinx literature, but when it came to the Puerto Rican literature, I was always looking at it two-fold — as a scholar and as a writer. This informs my fiction by the topics I select to discuss in my writing and how I can speak about that history. I can contextualize my work and make connections to past writers and also show where I diverge. Furthermore, when I read my work while revising, I am reading on three levels. I read as a reader, then as a writer, and then as an academic. Reading as a reader means relaxing into the story and focusing on how the narrative unfolds, letting the words and story overtake me. Reading as a writer signifies that I am then focusing on plot, if ideas hold up through the entirety of the text, if that phrasing captures my intended meaning, etc. Lastly, reading as a scholar means that I am reading with the whole of Puerto Rican literature from the continental US at my disposal, so I am making connections, thinking about a whole sub-group of fiction as I revise, and doing a scholarly analysis of my text. This allows me to easily switch perspectives and think about multiple audiences at once.

Why do you write? What’s at stake for you?

I write because I love reading, and what I want to do as a writer is recreate what reading has done for me — which is to give life to my thoughts, to offer validation of a world I see in my mind. There is this line from Tar Baby about dogs kneeling and I knew what Toni Morrison meant, and I felt she made material something I had thought about, so reading is about connection and being seen. The author validates a world I couldn’t articulate.

Also, there are lines that I carry with me by other writers — like “if love isn’t eternal, what’s the point?” by Sandra Cisneros, or “You your best thing” by Morrison. These lines function like prayers — they provide comfort. And I hope that is what my writing does — offer connection and comfort to readers.

+++

+