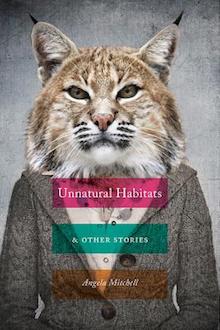

From a newly divorced woman employed by a front for illegal drugs, to a man who seeks revenge when the farm he loves is invaded by meth producers, to a shady Arkansas businessman wrestling with his own wildness (and that of his teen son) as he attempts to return a domesticated bobcat to its native habitat, the characters in Angela Mitchell’s debut collection Unnatural Habitats and Other Stories (WTAW Press, October 2018) explore the conflict between what is instinct and what is learned, as well as what it means to belong to a place and to a people. The seven connected stories are set in the rural landscape of the Ozarks of Arkansas and Missouri and focus on a growing crime culture in a place that had previously felt untouched by the world outside, forcing the characters who live there to reevaluate their sense of right and wrong. A land of dying farms with an aging population, and little opportunity available for the young who remain, poverty is at the heart of many of the conflicts. But even those characters who enjoy a certain wealth and privilege find themselves at odds—and out of step—with parents, children, lovers, friends, and neighbors. Like the Arkansas businessman who longs to reconnect with his most natural, primal self, the characters in these stories suspect that a better life is behind them and they are skeptical of what the future holds.

From a newly divorced woman employed by a front for illegal drugs, to a man who seeks revenge when the farm he loves is invaded by meth producers, to a shady Arkansas businessman wrestling with his own wildness (and that of his teen son) as he attempts to return a domesticated bobcat to its native habitat, the characters in Angela Mitchell’s debut collection Unnatural Habitats and Other Stories (WTAW Press, October 2018) explore the conflict between what is instinct and what is learned, as well as what it means to belong to a place and to a people. The seven connected stories are set in the rural landscape of the Ozarks of Arkansas and Missouri and focus on a growing crime culture in a place that had previously felt untouched by the world outside, forcing the characters who live there to reevaluate their sense of right and wrong. A land of dying farms with an aging population, and little opportunity available for the young who remain, poverty is at the heart of many of the conflicts. But even those characters who enjoy a certain wealth and privilege find themselves at odds—and out of step—with parents, children, lovers, friends, and neighbors. Like the Arkansas businessman who longs to reconnect with his most natural, primal self, the characters in these stories suspect that a better life is behind them and they are skeptical of what the future holds.

+

Nancy Au: I am particularly drawn to Dee and Gary and Layton, and their linked struggles with Bobbie. Without giving too much away (to someone reading this interview who has not yet read Unnatural Habitats), I wonder if you might share a bit about what we might see if we were to look in to the mind of Bobbie on the day of its homecoming?

Angela Mitchell: I love the idea of tilting the viewpoint of any storyline and seeing it from a different perspective, but I especially love it in this case. For the uninitiated, Bobbie is a domesticated bobcat (and I use the term “domesticated” loosely here, as no wild animal can truly be tamed), one that was brought home to live with Gary when she was very young. Upon Bobbie’s return to her old home, I think she feels confusion and fear and quite a lot of irritation (because Bobbie is absolutely done with cages), but I also like to think she feels an overwhelming sense of relief and comfort. Like all animals who have been brought into an artificial or unnatural environment for a long period of time, Bobbie has adjusted to her situation, but, in my mind, she’s never fully left her wildness behind, her instinct to preserve her own survival.

In so many ways, Bobbie symbolizes the conflict that exists in the human characters of the “bobcat trilogy” within this story collection. They’re all trapped, in some way, by their own bad or impulsive decisions, the families they were born to, the expectations the world puts on them because of what they look like or where they are from. But unlike Bobbie, the question of where they truly belong is more complex and not easily resolved by simply going back to their original home. Bobbie will find her way in the wild and all her instincts will return to protect her as she sets out on her own, but do the humans who kept her have the survival skills they need to thrive? I have my doubts.

In so many ways, Bobbie symbolizes the conflict that exists in the human characters of the “bobcat trilogy” within this story collection. They’re all trapped, in some way, by their own bad or impulsive decisions, the families they were born to, the expectations the world puts on them because of what they look like or where they are from. But unlike Bobbie, the question of where they truly belong is more complex and not easily resolved by simply going back to their original home. Bobbie will find her way in the wild and all her instincts will return to protect her as she sets out on her own, but do the humans who kept her have the survival skills they need to thrive? I have my doubts.

NA: Survival feels like one of the prevailing sensibilities running through the minds and lives of the different characters—survival in the wilds of adolescence and adulthood, survival while struggling to make ends meet, survival after the breakup of a marriage, survival of animals who’ve only known life in cages, who are later released into the wild. For a character like Dee who, in the story “Retreat,” “started to think she would have to choose between the dogs [that she reluctantly got in the divorce] or her life”—what would her dream life look like if she wasn’t running from her former life, if she wasn’t trying to “just” survive?

AM: Dee has the potential to be so much more than what she is, but she trips herself up, largely because she doesn’t know herself very well. She was taught to worry about how she looks and who she is with and what she can buy, but not how to find true, personal fulfillment. That said, if Dee could have any kind of life, she’d probably choose one where she could hang out by a pool all day, get mani-pedis and facials, and never worry too much about anything at all. She’d travel to beautiful places, where she would drink fancy cocktails and have enjoyable, but superficial experiences. But would she be truly happy living such a pampered life? I suspect not. The problem with Dee is that, underneath it all, she knows there’s supposed to be something greater to living, something deeper and richer, even if she’s never experienced it that way. She glimpses this kind of life during her involvement with Gary, but she can’t fully grasp it, can’t sustain it. Dee wouldn’t recognize this, but her real dream life would be one where she could settle in, feel safe and be comfortable and satisfied alone. Her dream life would be one less about survival and more about achieving satisfaction.

NA: The people in these linked stories could almost be seen figuratively as wild animals in a zoo, where loneliness and caginess seem woven into their very DNA. Escape in all its forms seems to rule the characters’ lives: divorce, breaking away from abusive bus drivers, violent ends to friendships and relationships. I am fascinated by stories where characters believe that loss or killing seems to be the only option for escape. In “Deeds,” Ivy says of Jody, “I should’ve drowned him as soon as he was born.” Where would you imagine Ivy would have gone to drown her son? What rituals would she have performed at such a heart-wrenching and disturbing event?

AM: As it is for most writers, themes reveal themselves in my work that I didn’t consciously consider during the writing process. In my personal life, I’m a terrible homebody and deeply sentimental. I long to travel, but when I arrive at my destination, I’m instantly homesick. I struggle to hold onto friends and family, even when those relationships have ceased to thrive. I also have a profound nostalgia for the home of my childhood, the Ozarks of southern Missouri, even though I haven’t lived there for any significant length of time since graduating high school (and, God, but I couldn’t get out of there fast enough back then). So it’s a curiosity to me why so many of my characters want so badly to run away from people, from places, and how they long to sever the most intimate of relationships.

I think these tendencies in my characters grow out of an unrequited need for independence and to start again (and again and again). Hindsight is 20/20, as they say, so when Ivy reflects on the disappointment her son, Jody, has turned out to be, she’s speaking from that place of regret and sorrow and an extreme desire to start over. She’s thinking about how she could’ve saved herself and so many others from the pain and destruction Jody wreaks if only she could have seen it all coming in the beginning. When I was a young teenager, my grandmother told me what women did in the old days when they gave birth to an unwanted child, that some would simply take the baby far into the woods, set it under a tree and walk away. I don’t know if this was really true, but it is an image that has haunted me, that anyone could do such a thing, even in the name of personal survival. If Ivy had known all that would come, all the heartbreak her boy would bring her and others, maybe this is what she would have done?

But the truth is this: even if she could’ve looked into the future, it would not have stopped her from loving her son. That’s the catch for all of us, that love—maybe even more than hate—is what so often gets in the way of what we might’ve done differently. I’ve said it before of my many unlikable characters, but it bears repeating that even the most horrible person in this world has had someone, somewhere who loved them. It’s the place in tragedy where a door is left open for redemption.

NA: There is such an incredible sense of yearning at the heart of many of the characters in Unnatural Habitats. As a reader, I desperately wanted all the animals (both the wild and the human kind) in these breathtaking stories to find their homes, to find their welcome. If you were to write a homecoming story for Layton, what would that look like? Or, what would you say to Tonya if she were your sister or friend, to help her find a “home” in her beautiful, plus-size body?

AM: In my imagined homecoming for Layton, I see him a humbled man, at least for a time. I would see him coming back to his wife and children with his father standing behind him for support, and he would make amends in his own, awkward way. But I would want more for Tonya, who is so tortured by her feelings about her body and how it defines her in this world.

“Pyramid Schemes,” the story in which Tonya appears, is one that often makes readers uncomfortable, mostly because they struggle to reconcile the notion that one can be beautiful and overweight, be both overweight and sexually active. I’ve come to hate it when I hear it said that a woman “has such a pretty face,” because it almost always means that she’s overweight and being overweight feels like a crime in our culture. Tonya has been hearing this about herself all her adult life and it’s carved away in her an emptiness she tries (unsuccessfully) to fill with makeup and clothes and sex and cars.

I would want to tell Tonya that she has everything she needs, that she’s gorgeous, yes, but that she’s smart and funny, and she can be with a man or without a man and be just fine. I’d tell her to let the hurt go, to put on that red lipstick and quit her teaching job and go out and do sales (because, clearly, that’s where her talents would shine through). And I’d tell her that her relationship with her daughter, Jennifer, is the one relationship that really matters, the one she absolutely has to keep safe. She can let the rest of it go, if that’s what she needs to do, but she and Jennifer have to hold onto each other.

NA: For my last question… I love bobcats! Why bobcats? What draws you, as a writer, to this glorious animal?

AM: I love bobcats, too, and they’re common where I’m from but rarely seen. It isn’t unusual, though, for one that wanders close to a house or subdivision to be captured and kept as a pet. This is almost always a terrible mistake. Even though they’re native to most of the United States, there’s something exotic about them and, as a result, people long to get close to them, to tame them.

The idea for Bobbie was born out of two different, real life bobcat stories I learned from friends. In one, a woman in an upscale, Arkansas suburb was sued by her neighbors for keeping a pet bobcat that came and went from her house, at will, through a cat door. In another real-life story, an acquaintance of mine found a bobcat as a kitten (presumed to have been abandoned by its mother) and raised it as a pet, yet it was never free to roam. It was, instead, kept in a wire enclosure and given a combination of cat food and dead animals to eat. Both of these incidences struck me as strange and sad and I wanted to find a place in my fiction to explore them more.

I have an early memory, too, of visiting my dad’s parents, who lived in a very rural place called Ravenden Springs, Arkansas, and of running my hands over a bobcat pelt they kept on the floor as a rug. My grandfather was a forest ranger for many years and, even before that, his life was one lived outdoors, mostly by necessity. He was never a man to hunt for pleasure, but when you live somewhere as remote as he did, killing for food or for defense (of yourself or of farm animals) is an unavoidable reality, and I suspect this bobcat had been one that had killed chickens or otherwise become a nuisance. In any case, my grandfather had preserved the pelt and I remember kneeling down beside it and looking at the glass eyes, tapping the cat’s fangs. The fur, as I recall, was in parts both rough and satiny. I knew it had once been alive and I pondered that, how what remained of this animal could still be so beautiful and entrancing, even in death. I knew I could never be so close to such a wild thing if it were alive.

There was something unnatural about being able to examine it as I did, yet, I was drawn to it every single time we visited. I have no idea what happened to that pelt—my grandparents moved from their secluded farmhouse into town and, shortly thereafter, the farmhouse was struck by lightning and burned to the ground—but I thought it about it often through the writing of these stories.

+++

+