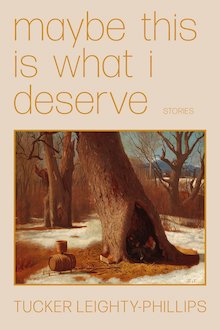

Tucker Leighty-Phillips is going to have to change his bio at some point. On his website, he tells readers that “Last year, [he] turned 31 and didn’t tell anyone. This year, [he’s] back in Kentucky for the first time in a decade.” I’m guessing he won’t stay thirty-one forever, and besides, his debut collection, Maybe This is What I Deserve, is about to be published by Split/Lip.

Winner of their fiction chapbook contest, judged by Isle McElroy, the book has already garnered praise from Matt Bell, Dana Diehl, and many others.

Maybe This is What I Deserve is filled with delightful uncertainty. It’s characters get into trouble for talking too much, ponder the trapped lobster in the grocery store, and look for fate in alphabet pasta. They make friends with their head lice, and, maybe, but not necessarily, their circumstances. It’s a book that asks do we deserve this? This? Whatever this life is? And how can we remake it despite our constraints?

+

Amy L Clark: One of the things I find most compelling about Maybe This is What I Deserve is that it’s so grounded in place. You could almost say that it’s about place: the specific state of Kentucky, yes, but also places and spaces we create for ourselves within our hometowns. So, I’ve got a lot of questions about place for you. What makes some stories stories that can only be understood through the specific geographical location in which they occur?

Tucker Leighty-Phillips: For a long time, I kind of assumed that being a writer was a city person thing. I’d never read a Kentucky writer. I read a lot, and enjoyed the books I read, but didn’t know Southern writers outside of Flannery O’Connor, and even then I didn’t feel connected to the place in her stories–it was moving, but it wasn’t home as I knew it. Then, in my mid-twenties, I stumbled upon Scott McClanahan, and felt an incredible attachment to his work that I hadn’t found elsewhere. He’s from West Virginia, but he was writing a place that resonated with me. There was Wal-Mart, and grandparent’s porches, and public schools. And it’s not just about the place, you know, it’s not like I’d never seen a porch in a story, but there was this emotional energy oozing through the stories, and that energy layered the setting in a way that felt wonderful and familiar. Kinda like the first time you put ketchup on eggs. That’s what I’m trying to do too–to not just write about places that make sense to me, but to transmit the energy of those places. To put ketchup on my eggs.

ALC: In “The Street Performer,” a man says, “You look like my childhood driveway,” and I love that so much. The narrator eventually responds to this by thinking: “And I’m forked, my lanes split at the thought of steering away this hurt man, this weary broken traveler. Who is not unlike him, trying to return to their childhood home, or trying to escape it for good? Who is not crooning a song of somewhere else?” You left Kentucky for a long time and have only relatively recently returned. Do you think you had to spend time away in order to create the version and vision of Kentucky that you put on the page? Like, I grew up in Maine, which I feel is another one of those places that is so specific culturally and geographically that the stories I set there could only be set there, but it’s also notable to me that I didn’t realize that until I had lived away from there. Also, I could never return to live anywhere near where I grew up. What makes some authors, and some characters, try to return to their childhood homes, while others try to escape for good? Do you consider yourself a regional writer?

TL-P: This is a really wonderful question–and to be honest, I don’t know that I would’ve considered myself a regional writer had I not moved away for so long. I think it’s valuable to complicate your sense of place, and living somewhere new can do that. It was helpful for me to live in other places, to see myself as a visitor, and to build a perspective of Kentucky through the lens of existing somewhere else. I started to understand its idiosyncrasies; what I liked and didn’t like, what I’d change, given the chance. When I write, I can’t help but write about Kentucky–it is a landscape that makes sense to me, and I’ve been intimate enough with it that I feel like I can relay that relationship thoughtfully.

ALC: Last question about Kentucky, I promise. I feel like I have to ask: what is it like to write there now? I’m thinking specifically about the political climate. I’m trans, so I’m particularly concerned about the recent spate of anti-trans legislation in Kentucky (where my best friend and my god-children live)? And I feel like there is some political consciousness in your stories. In “Statement from the Silver-Taloned Monster Ravaging the Local Townspeople,” the piece ends with: “He knows the clean, careful cuts with which his talons tear flesh feel almost more cruel than if he were lackadaisical about it. He doesn’t have any plans of stopping, but wants to assure the townspeople he hears their concerns. We’re a community, his statement reads, and I see you. I’m listening.”

TL-P: To be honest, writing in Kentucky isn’t much different from writing anywhere else for me. I mean, I’m privileged in a lot of ways, and my humanity isn’t being directly confronted with all of the recent legislation coming out of here and other places. So I’m kind of shielded, but also beholden to challenge this legislation and offer support to my trans, nonbinary, and gender nonconforming friends and neighbors. I read something a few weeks back about how the most radical culture comes out of the most repressed places, and I will say that in spite of everything, there are a lot of incredible people here. Activists, artists, cultural organizers; and they are deeply committed to staying here and fighting for this place they know and love, and I have an immense amount of respect for them and want to stay and do this work alongside them. Some organizations here that I admire are the Kentucky Health Justice Network, Queer Kentucky, and All Access EKY.

ALC: Several of these stories, notably “The Year We Stopped Counting,” and “The Year We Started Dancing,” deal with numbers. Others, like “Togethering” are explicitly about language. Running through all of this, it seems to me, is a question about or concern with what happens when mundane, everyday concepts get abstracted to a vanishing point. Tell me about your interest in idea-centered fiction.

TL-P: One of my first published stories was prompted by a defamiliarization exercise in Joe Scapellato’s Short Short Fiction class. I don’t remember the exact prompt, but I believe it was to take something intangible and make it tangible, and I opted to represent the concept of friendship as a legal agreement with a physical contract. One of the stories you mentioned, “Togethering,” was born out of a similar exercise in a class with Tara Ison when I was in grad school. I think I’ve primarily learned from writers who appreciate and work with defamiliarization, in making the mundane feel fresh, and so a lot of my work gets heavily conceptual as well. Sometimes, this approach allows me to explore an emotion in an innovative way. Sometimes, it just makes for goofy storytelling. Often it results in a lot of really bad first drafts.

ALC: Lol. I bet it does. I see many young writers, some of my students, who are really interested in writing “conceptual” fiction. Sometimes that makes for amazing, unique stories, and sometimes it means that characters, desire, the messiness of being human, are forgotten. How do you get to a good draft of an idea-based story?

TL-P: When I was teaching, I often compared storytelling to a soup, which maybe isn’t an original idea, but it worked for the students. Your concept might be the potatoes, you know, but a giant pot of potatoes isn’t a soup. There are ways to layer that concept and make it flavorful–maybe it’s a character want, or a dynamic relationship between two people, maybe it’s a fear that needs to be addressed. Throw all three of those in there and those could be your broth, onions, and cheese. I never actually demanded their stories contain x or y, but I did try to encourage them to push their stories to do more than one thing. You know, it’s the same thing with worldbuilding. I can’t remember who originally said it, but some early writers will create vast worlds and technologies and lengthy histories of intergalactic relations, but there won’t be a character story to be found. Sometimes you have to ask yourself – “what am I feeling right now?” and find a way to thread it into the story. Even if it’s a historical mermaid novel or something.

ALC: You write a lot of children characters, and I think you do so with an unusually attentive seriousness to the concerns of children. One of my favorite passages in the book is in “Every Good Boy Does Fine,” when the teacher, who has punished a boy for some unspecified infraction by confining him in a refrigerator box, finally removes it. You write, “She places the box in the corner behind her desk, says she’ll save it in case she needs to use it again. They stare at one another, both making a tremendous noise the other cannot hear.” What is your inspiration for, and interest in, writing about children and childhood?

TL-P: This actually relates to the concept of defamiliarization–I actually just taught a workshop about this. There’s this Hannah Gamble essay about teaching poetry to children, and part of its thesis is that the younger students were more inventive with language, because they’re still learning language, which means they haven’t really become nonchalant about it. The same is true for the human experience as a child–everything feels wondrous, or scary, or vast. There’s such a vastness to being a child that is lost when you settle into adulthood. Writing for me is a space to kinda recapture that feeling, even if it’s facsimile.

ALC: The bulk of this book is made up of flash and micro stories. I love writing, reading, and teaching these kind of little shorts. I find that most of my students are unfamiliar with the form, but that they also love it when introduced to it. How did you come to this form, and why does it appeal to you?

TL-P: I don’t remember my introduction to flash fiction as a genre unto itself, but when I was a kid, I was obsessed with Louis Sachar’s Sideways Stories from Wayside School. If you haven’t read it, it’s like Calvino’s Invisible Cities for children. Jia Tolentino published a New Yorker article about the series and calls them “lovely little lessons in craft, structured as neatly as a Rubik’s Cube.” I think that’s where my love for the form came from. When I first discovered literary magazines, I was working a series of service jobs–coffee shops, grocery stores, restaurants, hookah lounges; and I liked flash fiction because it felt like the literary form for time thieves–I often read stories in the bathroom at work, in the hallways and crevices where the boss’s cameras couldn’t see me. I read Wigleaf every week at work, which really expanded my understanding of contemporary literature and helped me build a relationship to flash fiction as a form, even before I was writing myself.

ALC: Maybe This Is What I Deserve is your debut. That’s awesome! What has the publishing process been like for you? What are your feelings about and aspirations for putting your work out there?

TL-P: This is a complicated question for me, because, if we’re being honest, the publication itself has also been the aspiration. I used to be a tour manager in the music industry, which meant I was basically the band’s administrative assistant. It was so strange to have such an intimate view of the artist’s most vulnerable experience–seeing a group of people risk everything, sharing their art on stage every night, hoping that it connected with someone in the audience (if there was an audience). For those musicians, creating something together and traveling the country to broadcast it was an almost-spiritual shared experience. I was always so desperate to be a part of that, to make something of my own, but I didn’t play an instrument and didn’t really have any other artistic talent. I think writing this book is a way of consoling that younger version of myself who thought he didn’t have anything to offer. And the publishing process has been fun. I’m not very interested in self-promotion, so I’ve challenged myself to make it unique and worthwhile; I can’t bear just sharing the preorder link over and over, but if I can find ways to make people laugh and take notice and care about the work, then I’m happy to do it.

ALC: Is there a question you’re dying to have an interviewer ask but that hasn’t come up yet? In other words, if you were interviewing you, what would you ask?

TL-P: Nobody has asked me which books I’d take on a desert island. I don’t have an answer yet, but I might whenever somebody asks me.

+++

Tucker Leighty-Phillips (he/him) is a writer from Southeastern Kentucky. He is a graduate of the MFA in Fiction program at Arizona State University. His work has been published in Booth, Adroit Journal, The Offing, Wigleaf, and elsewhere. He has been anthologized in Best Microfiction and received a Notable Mention in Best American Sports Writing. Tucker writes about poverty, Appalachia, children, and family dynamics. His work has been supported by the Tin House Writers Workshop, Kenyon Review Writers Workshop, Art Farm Nebraska, Craigardan, and the Virginia G. Piper Center for Creative Writing.

+

Amy L Clark (they/them) is a writer and educator. Their collection of flash fiction, Wanting, is published as part of the book A Peculiar Feeling of Restlessness, and their full-length collection of stories, Adulterous Generation, was published by Queen’s Ferry Press. Their novel Palais Royale is available from Engine Books. Other work can be found in in journals and anthologies including Come Sail Away, mac(ro)mic, Brilliant Flash Fiction, Wensum., Litro, Baltimore Review, McSweeney’s Internet Tendency, Fifth Wednesday, the Norton anthology New Micro, and many others. They teach creative writing and literature at Emerson College.