I met Donnaldson Brown when she joined the 2020 cohort of Bookgardan, the low-res writing program that I direct for Craigardan artist residency center. She’d already finished her first novel, and while she worked on her second she generously shared her unique, largely non-textual method for developing fully-dimensional fictional worlds and characters, likely informed by her background in film, theater, and visual art. Donnaldson’s sensitivity to place and the way her characters continue to live off the page are hallmarks of her fiction, as is her subtle, unobtrusive lyricism, all in evidence in Because I Loved You, her first novel, published this month by She Writes Press.

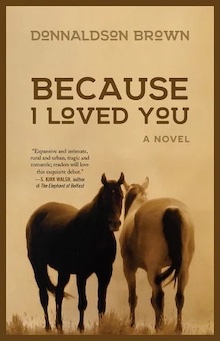

Because I Loved You’s 16-year-old protagonist, Leni O’Hare, dreams of escaping her family’s rundown East Texas farm to become an artist, but that would mean leaving behind both her mare and her beloved older brother. When she rescues the runaway horse of Caleb McGrath, younger son of the largest rancher in the area, Cal catches her heart with his gentle nature and his own big dreams. Together they begin to plan a future beyond the confines of their small town. But driven by a family tragedy and Leni’s deeply held secret, she hastily makes a decision that she believes will protect Caleb’s future. Her ill-conceived, painful choice transforms not only their lives, but that of the next two generations. Donnaldson Brown takes readers from the Texas chaparral against the backdrop of the Vietnam War, to New York City’s vibrant downtown art scene in the 80s, to the present day; from dreams lost to dreams reimagined. She tells an epic story of abiding love—romantic love, parental love, and the kind of love that sets a person free to choose her own path and maybe, one day, return.

What I love most about Because I Loved You isn’t the tactile reality of places and times that Donnaldson so sharply renders – the harsh beauty of the East Texas chaparral and New York City in the simultaneous throes of AIDS and guerilla art and Wall Street’s financial obscenity – but her ability to feel so deeply into her characters that even as they make shattering mistakes we can believe along with them that their actions are exactly what they need to do in the moment, just as they convince us of who they become in consequence. Donnaldson has the deepest empathy for imperfect humanity, and her people and their lasting impact on each other is so knowable it makes you ache.

+

KM: Do you recall how this story came about? I’m always interested in origin stories.

DB: I remember very clearly. It began with the image of a girl galloping her gray mare hard across the chaparral. I couldn’t shake her. I could practically hear the horse’s hooves strike the ground. I needed to know two things simultaneously – what is she running from and where is she trying to go. That just stayed with me. Then I knew – I’m not certain how we know these things, but we do – she’s in Texas. She is running from her mother, and running from their run-down farm (although there was a lot of love there too, she adored her brother and her father, but I didn’t know that yet). Then the scene comes to a screeching stop and there’s this young man. Oh, who is he? What struck me at first about these images was that he was standing still. When I focused on the girl, Leni, she kept galloping. She was always in motion.

I’m asked sometimes if my prior screenwriting plays a role in my fiction writing. I never knew how to answer that question. Fairly recently, I realized that everything I’ve ever written has started with an image that rolls into action.

KM: That reminds me of a related question: how live theater has affected you as a writer. Maybe this originating image speaks especially to theatre because of that idea of movement. Not necessarily only physical movement, but that sensation of someone whose energy is driving them forward, maybe even heedlessly.

DB: I never really thought of it in relation to theater, but I understand what you’re saying. Leni’s drive, her inability to stand still is important to who she becomes. She’s not one to stop and process what she’s going through, she wants to keep moving. She’s almost afraid to look back. As the novel goes on, her art expresses her past in very specific ways.

KM: Such an important part of this book is how the past colors your life, even if your desire is to leave it behind and you think you’ve done so. Did you know that this was the story you needed to write?

DB: Yes and no. I think often the dreams we have for ourselves at a very young age hold real truths for us, a heart’s desire, if you will. Some stay true to that, while others get diverted. Why is that? That was a question I wanted to explore. How do some of those experiences in our youth – things like first love, and the places where we grew up, how our parents, or even our peers, treat us – impact those dreams? No one can escape the past, much as we might want to. I think our attitude towards our past can be quite determinative, and that interests me very much. What of our past do we accept, what do we reject? Does where we came from feel like something solid we can stand on, or something we shun? I’m not an outliner. I’m sure I’d save myself a lot of time, if I were. (laughing) I write by the ‘seat of my pants,’ as the saying goes. So, that meditation on whether and how one stays on a path, and what happens when momentous decisions are forced on us in our youth, got me started. Leni and Cal took it from there.

KM: What’s your own experience of the contrail of the actions of your younger self?

DB: Ah, that’s a big one. Do you think people really want to know this? (laughing) Well, I knew as a girl and young teenager that music and acting were my heart’s desire. I knew I was going to be in the theatre. As a young girl, I adored my father, a deeply flawed man, and an alcoholic, but gentle in many ways. He walked out one day when I was playing upstairs, without saying goodbye. I only saw him a very few times. I knew, though, that he thought acting was not an appropriate pursuit. His disapproval, along with the insecurity that followed his abandonment, led me to walk away from acting and music. For a long time, writing felt like something of a consolation prize, if you know what I mean. I don’t feel that way any longer. And I sing and play guitar now whenever I have the chance.

KM: I feel profound sadness for Cal and Leni. This is what tells me that you’ve really gotten your story and gotten to the heart of your characters, because I think about them separate from the pages of the novel. I think about them as human beings, kids, these two teenagers with families struggling (in very different ways). I think about the backdrop of the Vietnam War. The reality of life’s fragility comes at them full force, along with the lasting consequences of their actions.

DB: Right. Leni and Cal, as sixteen and seventeen-year-olds, make huge decisions. The thing is, we don’t know what we don’t know, not to echo Donald Rumsfeld here. (laughing) But don’t you remember how when you were a teenager, or in your twenties, even in your thirties, you thought you knew so much, everything.

KM: Yes, exactly. I think of that, looking back for any of us, the stupid or destructive things we did when we were too young to know how young we were. Sylvia Plath and Ted Hughes were so young, and the consequences of their actions . . . Oh my god.

DB: Yes. I know this ties into themes that you’re interested in, in your own work and in general.

KM: I would argue that there’s an element to Leni’s fierce protectiveness of her art that may be a reflex to keep from having to feel her feelings. This isn’t to denigrate her or her achievement. Isn’t there a point, though, when she claims she doesn’t show her work, because she wasn’t making the kind of art that people wanted to see in those days?

DB: Right. She wasn’t. But we can’t always, maybe often, dictate what it is we need to express. Witness: this novel. (Laughing)

KM: Others see what she’s doing and recognize its power and beauty. In her paintings and drawings, Leni can’t seem to shake the expansive, dreamlike prairie landscapes. Like her past is leaking out of her.

But she continues to protect her art, and her self, too. It’s both genuine, and it’s a defense.

DB: Yes, in some ways, she’s very guarded. When the story picks back up in New York, Leni and Caleb are both in their early 30s. She’s part of the generation of New York artists responding to the Reagan-era, a time of accumulating wealth, conservatism, and dismantling social programs. Some artists pushed back with radical social activism in their work. They created a downtown epicenter for art in the streets and abandoned warehouses. She is a Guerrilla Girl type. Leni takes great risks and is making, what I think, is a really interesting life for herself – a life she’s fiercely protective of. It comes at a cost, though. Sometimes we make choices that cut off more of ourselves than we may intend. Caleb in his own, different, way does something comparable. Some things that happen in a life are like an earthquake that changes the course of a river.

KM: It seems that for Caleb the place he came from was almost radioactive.

DB: His father’s dream, which would require Caleb to give up his own dream, is for Caleb to take over the businesses. This reflects his father’s narcissism. It also, though, is what his father believes is the most important thing he has to give: not his acceptance or his love – which of course is what Caleb, what any child, really wants – but the ranch and all that comes with it.

KM: This brings me to Leni’s French mother, Ludevigne, who is the only point-of-view character other than Leni and Caleb, although her part, important as it is, is brief. Leni clashes with her mother, who she sees as “wrapped so tightly inside herself, it’s a wonder she can exhale.” At one point later, though, Leni says she, “wants around her only enough space to breathe. No more than that. No wide sky. No horizons. No far fields. No birds in flight. No stretching in any direction. Everything contained. Tight. Precise.” This reminds me of Ludevigne, who lost so much during World War II, then married an American medic from Texas, perhaps not understanding he was a small-town vet rather than a doctor. For most of the book she seems haunted by deprivation and so out of place. How did you end up with this character?

DB: Why is the mother French . . .? (laughing) When Leni was galloping across the chaparral in that first image that came to me, she was running from her mother. And her mother was yelling after her in French. It surprised me, too! Outsiders do call to me. I think we all feel ourselves to be outsiders at one point or another, maybe more often than that, sadly. How do we find our place, how do we connect with one another? These questions keep me up at night.

Leni does echo her mother in that scene you alluded to, much as she wanted to reject her mother. What we react against often threads its way through our life, doesn’t it? For Leni, this is just before she makes one of the most important decisions of her life.

World War II was Leni’s mother and father’s war, and it leaves a residue over the family. An astrologer once told me once that in prior lives I’d been a warrior. I can’t know if that’s true, of course. But the specter of war has always haunted me. I have three older brothers, two of whom were draft age during the Viet Nam War, which Walter Cronkite and Eric Sevareid brought into our kitchen every night. And my mother’s first husband died in World War II. My mother had two young boys at the time, two and a-half and five years-old.

KM: Oh, no—

DB: My father adopted the two boys when he married my mother. There were photos of their birth dad around and always in my mind this presence of the war that took him, and what my brothers lost.

KM: You had horses in your earliest life and you still have horses in your life, but in an expanded way. I’m wondering how your lived knowledge of the limbic connection between humans and horses found it’s way into the novel.

DB: It’s a connection that is so deeply ingrained in me. I think it found its way into the novel in Leni and Cal’s love for their horses. Those are central relationships for each of them. Horses are what first brings them together. And they weave in and out of the novel, kind of circling Leni and Cal and drawing them together as the story progresses.

KM: Can you say something about your work with veterans and PTSD and horses?

DB: I had wanted to work with veterans from the time we first started hearing of the suicide rates for veterans coming home from Iraq and Afghanistan. For a long time, I didn’t know what I could possibly do. I’m not a veteran.

KM: Not in this life, anyway.

DB: Exactly! (laughing)

DB: In 2014 or 2015, I started thinking, I could teach yoga. I’d been practicing for many years at that point. So, that led me to take my first (of many) yoga teacher trainings. Soon thereafter, I did a trauma-sensitive yoga training with the Veterans Yoga Project. In 2019, I did a theater intensive at Shakespeare & Company in Lenox, Massachusetts – giving myself a taste of the theatre I so desired in my youth. There I met an actor who was also a veteran. He told me about The Equus Effect, which is the organization in Sharon, Connecticut I’m now involved with. We offer an experiential learning program with horses for veterans, first responders, and others coping with PTSD. The program includes a form of somatic experiencing, along with some education about emotional regulation. The horses are amazing teachers. I started as a volunteer, and am now a facilitator and help to train facilitators.

KM: When Caleb’s brother, Hank Junior, comes back from Vietnam, nobody cuts him any slack.

DB: Yeah. They don’t know what he needs. You know, he’s so angry and so reactive. He does some very dangerous things. He also, though, does a beautiful thing. The other characters don’t know about that, though. I really love Hank Junior. Well, I love them all. Very much.

KM: Your empathy for your characters, for humanity, is your super power.

DB: Thank you. That’s very kind of you. Wendell Berry said – and I think it’s so important, “you have to be able to imagine lives that are not yours.”

KM: Thinking back to that initial image of yours – the girl galloping away and the boy standing still – I definitely detect your experience in theatre and performance, and in the film industry in your visual and sensory acuity. Beyond the emotional nuances of character, you zero in on the emotional power that setting can conjure, and are so sensitive to the particular details that evoke a moment. Even in your descriptions of Leni’s paintings, you pick just the right elements for the reader to feel their reality, and to know why Leni is so compelled but also so private about her art. You also paint the historical moments so vividly – the Vietnam War, New York in the 1980s, when the art scene and the financial world were at such opposite ends of the cultural spectrum. How much of this is from memory and how much imagination and research?

DB: I actually did no research. About the Texas chaparral – after my dad left, some of the only times I spent with him as a girl and as a teenager were at the ranch that he and my uncles and aunt had in East Texas. I loved horses from as early a time as I can remember. Going to Texas and riding, being able to see my dad and ride with the cowboys was hugely impactful. I’ve always carried that with me. I grew up in western Connecticut, and I fled as soon as I could, at seventeen. As you know Leni wants to get out of where she grew up, but she dearly loves the landscape and the animals. That’s all part of her, and a big part of her art. After college, in the mid 1980s, I was drawn to New York City where I met the man who would become my husband. He was an artist. I was in law school during most of that time. I was an observer, at close range, of the art scene.

KM: I want to talk about the idea of motherhood, women and sacrifice. It’s usually the woman who doesn’t get to achieve her dreams. Which is part of why I see this as such a feminist story. I know you’re also a mom and you’ve been doing work in the creative world for a long time, but at the same time you had this other successful career. When you were in Leni’s position, so to speak, young and having to choose how you would invest in your life and your dreams, how did you make those decisions?

DB: There are two strands to answering that question. One is, frankly, my own insecurity. I didn’t think that I could be an artist. My family was certainly not supportive of that. Part of becoming an adult, of course, is learning to make your own decisions. But I felt I always had to have an alibi. When I was a student, my alibi was good grades, and I loved school. I loved learning. Then when I got older the alibi was, I’ll be a lawyer. I like words, I like to communicate. I always wrote on the side. It was years before I could say to people that I wrote. So, I didn’t handle it very well and wouldn’t recommend that route to young artists. (laughing) Then when we had our son, I thought well, I’ll give my son his own neuroses. I’m not going to give him mine and abandon him. I was working in film at the time and definitely made choices that pulled me way back from what my career could have been. I adored being a mom, though, and I adored my son – still do! But it was a big sacrifice. That was hard.

KM: It’s a biological conundrum. What do you do when it’s your body that’s called upon? Motherhood requires a kind of openness, just like art. When my kids were small, I realized that art-making and children wanted the same thing from you – your full attention and availability. How to do both?

DB: It’s a struggle for sure. And I think life is often sequential. We can do a lot in our life, just maybe not at the same time, which can be hard if one’s impatient, as I am. (laughing)

KM: Can you say what it is that you wanted for Leni and Caleb?

DB: That’s an interesting question. I think they lived the lives they needed to live. And in the end, we discover how their lives, their later choices, in fact liberate one of their families (I won’t say whose) and even future generations in a surprising way. It surprised me. But it feels right. Sometimes our lives are to resolve not only our pasts, but something of our ancestors’, as well. We can clear the way somewhat for those who come after us. That’s important. Every life is so important.

KM: Thank you.

DB: Thank you, Kate. It’s been such a pleasure talking with you.

+++

Donnaldson Brown grew up riding horses on her uncles’ ranch in East Texas and in her hometown in Connecticut. Her debut novel, Because I Loved You, is due out in April 2023 with She Writes Press. She is a former screenwriter and worked for several years with Robert Redford’s film development company. Her spoken word pieces have been featured in The Deep Listening Institute’s Writers in Performance and Women & Identity Festivals in New York City, and in the Made in the Berkshires Theatre Festival in Stockbridge, Massachusetts. She’s a past fellow of the Community of Writers (formerly Squaw Valley Community of Writers), Virginia Center for the Creative Arts, and Craigardan. Ms. Brown is a longtime resident of both Brooklyn, New York and western Massachusetts. A mother and former attorney, she is currently a facilitator and trainer with The Equus Effect, which offers somatic based experiential learning with horses for veterans, first responders and others struggling with PTSD. Find her online at donnaldsonbrown.com.

+

Kate Moses is an internationally acclaimed novelist, journalist, and writer of memoir. Her novel Wintering, published in seventeen languages, received a Lannan Fellowship, the Janet Heidinger Kafka Prize, a Prix des Lectrices de Elle and other honors. She is also the author of Cakewalk, A Memoir and coeditor of the bestselling anthologies Because I Said So and Mothers Who Think, which won an American Book Award. A former acquiring editor at North Point Press, literary director of San Francisco’s Intersection for the Arts, and a founding editor and staff writer at Salon, she served on the graduate faculties at San Francisco State and University of San Francisco. She now runs Birds & Muses, offering literary mentorship to women writers, including Bookgardan, an advanced, low-residency book mentorship program cosponsored by Craigardan arts center in the Adirondacks.