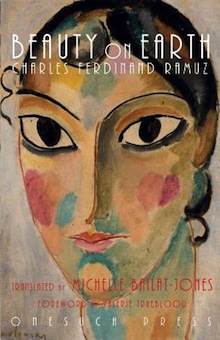

Our Translation Notes series invites literary translators to describe the process of bringing a recent book of fiction into English. In this installment, Michelle Bailat-Jones writes about translating Beauty On Earth by Charles Ferdinand Ramuz (Onesuch Press).

+

Generalities:

It all begins with language. How do these words work together? Who is speaking and how does this person speak? What does that voice sound like in my head?

It all begins with language. How do these words work together? Who is speaking and how does this person speak? What does that voice sound like in my head?

Translating is not so different from writing fiction, except that the voice comes from a different location, is both outside of me (because I haven’t written it) and inside of me (because I am reading and re-writing it).

I first read Beauty on Earth without any idea that I might translate it. This is years ago now and the only thing I remember from this reading was the excitement of recognizing places close to where I had just moved in Switzerland—Ramuz’s descriptions of the mountains, of the lake, and especially of the weather felt very true to this new life I was leading in a small village near the Lavaux vineyards. This was a careless read, fast and joyous. Exciting because it was a discovery of a writer whose work I knew I would go on to read as much of as possible.

But once I knew I wanted to translate the book, I read it again. This time with calculation and a deeper curiosity, already trying out a few sentences in English, looking past the story and wondering about how this book had been written, wondering about its smooth arc as well as the stops and angles that break it up into a careful structure.

Reading and re-reading is, at least for me, the best research into a translation. I have to start to know the text, to have a feel for what is coming next so that when I start working on a scene or a description in English, I know what comes before it and what comes after it. I need to have the book’s chronology and emotional shifting already imprinted a little in my memory before I can feel comfortable moving it all into a new language.

+

Particularities of Beauty on Earth:

There were moments while working on Beauty on Earth that I had to stop, go back, and start to read again. Part of this had to do with Ramuz’s insane shifts in perspective. At times it is hard to know whose voice he is using or where exactly the narrator is situated with respect to the story and the characters. He can change POV between sentences. Something that makes his work so unique is that there are times that, in the middle of a scene, when you think you’re reading a very comfortable 3rd person, he suddenly shifts into a chorus-like voice and a few lines later, into a first person plural. It can be really jarring—and my temptation as a writer (and what I did in my first few drafts) was to smooth this out. But I had to check myself, because this is part of his world and is just as disorienting for a French-language reader. I eventually developed a coding system, circling the various pronouns with different colors so that I could see their pattern on the page and check and double-check how I was handling them in English.

About halfway through my translation I remembered that I had a copy of Ramuz’s complete journals and perhaps Ramuz had written about the novel. Unfortunately, he wrote very little in his journal about the genesis of Beauty on Earth. At the end of September 1926, he mentions that he’s made notes and an outline for a project he is calling at that point, Beauté Terrestre. He writes, “All other work put aside.” His journal is empty then until the end of November. But I was stuck a little on Beauté Terrestre, thinking about this title compared to its published title of La Beauté sur la Terre. It’s interesting to me that either way, in English the title can really only be Beauty on Earth. Interesting because I think Beauté Terrestre is a weaker title, a bit softer, a bit less appropriate for a book that is essentially a criticism of society’s inability to understand/know/handle real beauty. In that sense, the English title is also a bit weaker than the French. “La Beauté” is an ideal as well as possibly a person. And it sounds so much more definitive.

Beauty on Earth is set in a small village, and much of the action occurs out on Lake Geneva or on the hillsides surrounding the village. This meant that the book contains tons of references to plants and trees and other elements of the natural world, very specific words—and some of them particular to Swiss French—I hadn’t come across before. I kept this short list of (beautiful) words taped next to my desk:

- biolle/bouleau (birch)

- molasse (molasse – sandstones)

- saponaire (soapwort)

- mélilot (sweet clover)

- prêles (horsetail ferns)

- angéliques (wild celery/garden angelica)

- vernes/aulnes (alders)

- fauvette (warbler)

- chardonneret (goldfinch)

- bergeronnette (wagtail)

And finally, although this falls into the accidental research category, Beauty on Earth is about a young woman named Juliette, orphaned in Cuba upon the deaths of her Cuban mother and Swiss father, who must then travel to Switzerland to live with her uncle and work in the café he owns and runs on the shores of Lake Geneva. So in the simplest sense, much of the novel is about a foreigner who comes to settle in a small Swiss village and her disorientation and dislocation from the home she knew before. As it happens, I’ve been researching this very experience for the past eight years.

+++

Michelle Bailat-Jones is a writer and translator living in Switzerland. Her fiction, translations and reviews have appeared in various journals, including The Kenyon Review, PANK, Hayden’s Ferry Review, The Quarterly Conversation, Two Serious Ladies, Cerise Press and Fogged Clarity. She is the Reviews Editor here at Necessary Fiction.