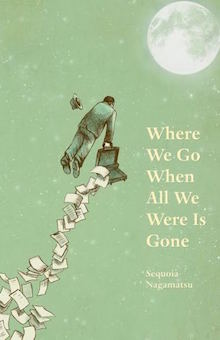

Our Research Notes series invites authors to describe their process for a recent book, with “research” defined as broadly as they like. This week, Sequoia Nagamatsu writes about Where We Go When All We Were Is Gone from Black Lawrence Press.

+

Where We Go When All We Were Is Gone is a collection of stories inspired by Japanese folklore and pop-culture, but I am a fourth generation Japanese American. So, where do these stories come from and what do they mean? I’ve always been fascinated by myths, folktales, legends, and monsters. As a kid, I had a poster of a map of Bigfoot sightings on my door. I spent hours at the local bookstore, reading about Hitler’s quest for the Spear of Destiny, flipping through the Egyptian Book of the Dead, and imagining Spider Grandmother helping the Hopi emerge from the Earth from their former world. I ended up taking this fascination with me to college where I majored in anthropology, long before I considered taking my writing more seriously.

Where We Go When All We Were Is Gone is a collection of stories inspired by Japanese folklore and pop-culture, but I am a fourth generation Japanese American. So, where do these stories come from and what do they mean? I’ve always been fascinated by myths, folktales, legends, and monsters. As a kid, I had a poster of a map of Bigfoot sightings on my door. I spent hours at the local bookstore, reading about Hitler’s quest for the Spear of Destiny, flipping through the Egyptian Book of the Dead, and imagining Spider Grandmother helping the Hopi emerge from the Earth from their former world. I ended up taking this fascination with me to college where I majored in anthropology, long before I considered taking my writing more seriously.

I didn’t mention anything about Kappa, Japanese water imps, or dragon lovers at the bottom of Lake Tazawa, Japan’s deepest lake, because my fascination with the fantastical realms of Japan didn’t come until much later. In fact, anything Japanese apart from teriyaki and an occasional trip to the local sushi bar, was largely devoid from much of my life by my own choosing.

It’s probably important to note that I spent most of my childhood in Hawaii, where there is a large Japanese American population. My great-grandmother came to the then United States Territory as part of an arranged marriage in the 1920s. During WWII, Hawaii could only send a very small fraction of those with Japanese ancestry to internment camps due to the demographic of the islands, an experience my grandfather’s family in San Francisco unfortunately could not escape. At least half the students in my grade school classes had Japanese last names — Ito, Otane, Ishii, Ozawa, Yamashita. And most of the teachers were Japanese as well. The last names of my friends? Gonzales, Evans, Tupinio, Friend, Cruz, O’hale. At the time, I didn’t think this was weird. But, in retrospect, it’s abundantly clear that I was distancing myself from my own heritage, although I couldn’t tell you exactly why. Society imposed self-hatred? Perhaps.

I never asked my grandfather before he died about his time in the internment camp, but I knew his packrat sensibilities stemmed from once having to give up everything he owned. I never asked my great-grandmother about what her life was like in Japan. Large segments of my family history will probably never be recovered. I only know fragments, and the fact that much of my family is not on speaking terms with one another doesn’t help matters.

My great-grandmother was from Yamaguchi Prefecture (just south of Hiroshima).

She had a sibling who died very young and whose grave was washed away by the ocean.

I know my great-grandfather was a hard man who worked with his hands.

He played the violin, and he made wooden swimming goggles for local children.

I remember being shown black and white photos of my great-grandmother’s family, but no one knows where those photos are now.

In many ways, the connection to my heritage has become a myth.

When I moved to Japan in my mid 20s, it was to escape/reset my life. A lot of people would be thrilled at the chance to experience the country, but I initially saw my time there teaching English as a kind of salve. As a stealth foreigner, I found myself in an interesting position. I had to make myself known to other ex-pats for companionship, but I also had to make clear to Japanese nationals that I needed help finding my way through the city or a menu. I spent a lot of time on trains for work, soaking in the countryside while pushing Japanese businessmen, who had fallen asleep, off my shoulder. When I returned home late at night, I wrote, something that has always been a constant in my life. I workshopped my stories on the community zoetrope.com, where I realized that writing was something I wanted to pursue seriously.

While I wrote, I usually had Japanese variety or cooking television shows playing in the background, hoping for the occasional English language program or movie to air (Note: English programming was pretty limited, so I watched pretty much anything when it came with gusto). Two broadcasts in particular proved influential. The first was about young, working homeless men living in Internet cafes, which led me to Tokyo, where I stayed in Internet cafes myself. I did not have the language skills or the courage to speak to the men I saw, so I just observed and ate my vending machine ramen dinner like they did. The experience led to a story called “Melancholy Nights in a Tokyo Cyber Cafe,” which would end up in One World: A Global Anthology of Short Stories, my first print publication.

Another English language television feature showcased Yokai (a term for Japanese monsters) and the Legends of Tono (a collection of tales surrounding the town of Tono in Iwate Prefecture by Kunio Yanagita, arguably the father of Japanese folklore). Given my love of folklore, I immediately began Internet research, and made plans to travel to Tono and other locales of folktales and strange stories for vacations (i.e. a village in Aomori Prefecture that claims to be the resting place of Jesus Christ). Typically when I research, it is largely internet based. But considering I was in the country, I felt I owed it to myself to experience the real world settings of the stories that fascinated me. If a legend mentioned a gateway to hell or a cave full of demons, I wanted to go there [Message me for directions].

The seeds of most of the stories in the collection started in Japan, but it would take the years of my MFA program and some change to realize the book. And I think a couple of considerations hung over me from the beginning: Who am I to be telling these stories? And What exactly are these stories supposed to be? The fantastic in literature whether it be invoked folklore or futuristic possibility has often been used by writers to comment on society and self in chaos or transition (and this is certainly true for Japan, a country that has had to reinvent itself quite rapidly multiple times). Folk as nostalgia. Folk as connection. Folk as an ambassador of a past that can no longer be reclaimed. Folk as an aspect of ourselves that we don’t want to recognize or can’t come to terms with. The stories in my collection star Japanese water imps, Godzilla, a famous ghost, a snow woman, and a demon who can stretch his neck to incredible lengths. They are my anchor to a past and heritage that I can only partially claim. They are my lens to dig at the wounds that are unique to me and those that we can all recognize. And the worlds that I’ve created for these creatures, a hybrid of Japan and my Japanese American self, is where I hope, to quote a line from one my stories, “Make chaos somehow make sense”.

+++