Our Research Notes series invites authors to describe their process for a recent book, with “research” defined as broadly as they like. This week, Lise Haines writes about When We Disappear from Unbridled Books.

+

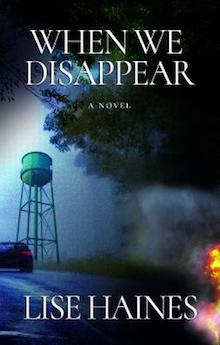

When We Disappear, my fourth novel, comes out June 5th, 2018. As you can see, the cover art depicts a car driving off, a water tower, a misty-looking wooded area, and at one edge something on fire. Two first-person narrators, a 17-year old girl and her father, tell the story of a hit-and-run accident in Chicago that damages many lives.

When We Disappear, my fourth novel, comes out June 5th, 2018. As you can see, the cover art depicts a car driving off, a water tower, a misty-looking wooded area, and at one edge something on fire. Two first-person narrators, a 17-year old girl and her father, tell the story of a hit-and-run accident in Chicago that damages many lives.

The book required at least two types of research. One had me pursuing information on rear bumpers, ignition switches, fuel lines, and so on. The other moved me through internal landscapes that stretched back a number of years. Both offered the possibilities of fresh collisions.

I’m one of those people who enjoy the discovery of information, traveling to locations and calling experts out of the blue. When I was in town I rode to the top of the Sears Tower (now called the Willis), to feel height-sick over the city I had grown up in and the murky lake where I used to swim. I had to find out something about the cemetery between Evanston and Chicago, only to discover I have family buried there. I took looping pictures on my phone and drove down streets as if I was casing the area for a crime, slowing to inspect homes and cars and streetlights. My young narrator is a photographer and shares my photography addiction. I thought about my old darkroom days and read up on camera bodies and lenses, and started to fill in gaps, and turned over the idea again of what a photograph can do, and who has done them particularly well.

The first place I lived was in an apartment in Rogers Park, in Chicago. The dining room and bedroom windows looked out to that cemetery and that broke my mother’s heart and my smaller heart inside of her. This was two blocks from where my first love would have an apartment and shoot up speed, and tell me he loved me — quickly. It was three blocks from where my stepfather, Norton, would have an apartment for years so my sister and I would always have a place to return to after our mother died, to look out at the flat lake that wouldn’t go away. It was four or five blocks from my first apartment as a college student where the elevated train flew by within twenty feet of my living room. And it was an area where the photographer Vivian Maier went through dumpsters in her latter years. Like the direction on a compass that will not budge, this became the place where my characters would reside.

But the neighborhood had changed. It’s still rundown, the wheels on the elevated cars continue to squeal and it’s stifling as hell in the summer — yet some engineer had the rotten idea of revamping the elevated platform. Now there’s concrete everywhere instead of wooden supports like old roller coaster beams. I had clearly seen my female protagonist looking out at a wooden platform from her bedroom window in a contemporary Chicago. So I lied, ignoring my own research, and gave her that view of rickety supports and the daredevils who walk out on the tracks hoping to avoid the third rail.

As I began my novel, Nort still lived in that Rogers Park apartment by the lake. He had Alzheimer’s for years and he was my best friend. He knew everything there was to know about Chicago. He had grown up on the West side, the son of Russian Jewish immigrants. He had been a reporter with the City News Bureau, the political editor of a Chicago daily paper, and worked on Harold Washington’s campaign, the city’s first African American mayor. Nort knew every neighborhood and its complexities, and I wanted to ask a million questions for the book. All I could do, however, was hold his hand and go on conversational journeys with him that felt like driving round and round the same block. The book is dedicated to him though he’s gone now.

It is, as I say, a book about a father and daughter relationship, but I had another father to reflect on, a biological father named Roy, who had a terrible time being the good man he imagined himself to be. It was somewhere in the nature of unavoidable, internal research, when I was well into writing When We Disappear, that I discovered a precise memory. Roy once told me he had been out driving one night when his car hit a man on the road. The man flew up and hit his windshield. I don’t recall if he said the windshield cracked. And he couldn’t tell me if the man survived. If I had to make a guess, the driver had been drinking, heavily. My father’s voice sank lower and became almost melodic, as he got to this point in his story. He smiled as if he was full of the kind of shame that freights pride. He said he’d gone to see the judge in the case, and he had paid him off. This father had a way of holding his guilt and then quickly suggesting we go bowling or drive out to Arlington Race Track to look at the horses — or could he treat me to a hot fudge sundae?

Maybe I like writing fiction more than memoir since I don’t have to spend too many days and nights traveling backwards through this type of inner landscape. You understand the perils with any writing, but you can always go online and look up carburetors or fly fishing or lemon peelers and get right with your fiction gods again. You push into vivid worlds of your own design, your own making, with characters that refuse to be you or yours — the best or the worst — and you’re off again, on another journey.

+++