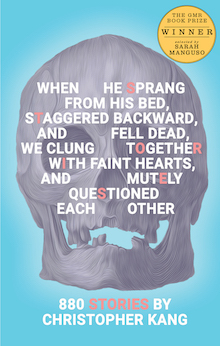

Our Research Notes series invites authors to describe their process for a recent book, with “research” defined as broadly as they like. This week, Christopher Kang writes about When He Sprang From His Bed, Staggered Backward, And Fell Dead, We Clung Together With Faint Hearts, And Mutely Questioned Each Other from Green Mountains Review Books.

+

1.

Write a novel with long sentences and long paragraphs. It feels important and difficult. It feels important because it is difficult. The novel has a one-word title. This conveys its importance. Its universal appeal and its urge to grasp the immutable qualities in a world that tends toward transient concerns. Think: Don DeLillo’s Underworld. Think: Knut Hamsun’s Hunger. Think: Jane Austen’s Persuasion. Think, think, think. “Think again,” your future self turns to you and says, “about writing this novel.” You don’t hear it.

Write a novel with long sentences and long paragraphs. It feels important and difficult. It feels important because it is difficult. The novel has a one-word title. This conveys its importance. Its universal appeal and its urge to grasp the immutable qualities in a world that tends toward transient concerns. Think: Don DeLillo’s Underworld. Think: Knut Hamsun’s Hunger. Think: Jane Austen’s Persuasion. Think, think, think. “Think again,” your future self turns to you and says, “about writing this novel.” You don’t hear it.

+

2.

Marvel at how the pages accumulate. Print them out on thick, expensive paper that produces a glare when held up to the harsh light of your desk lamp bent like an elbow to face your face. The book is so important. Otherwise why would you spend so much on the paper?

+

3.

Repeat to yourself that it is important. It is not important. But you don’t know that yet. What do you know? You know that you want to finish the book more than you want to write it. You don’t know that this is a problem. Not yet.

+

4.

When friends ask you what the book is about, you can’t give them a straight answer. You tell them you want to see what long sentences and long paragraphs can do. It is a terrible answer. It is barely an answer. You know the truth. In intermittent moments of terrifying clarity you know the truth about the book. That it is a big receptacle for verbal acrobatics and that it has a heart that barely beats. Writing as resuscitation.

+

5.

The book isn’t bad but it’s making you a bad writer. No, that’s not right. An unhappy writer. It’s making you an unhappy writer. You’re fine with being an unhappy person. That’s okay, that’s fine. But you don’t want to be an unhappy writer. That’s not to say you want to be a happy writer. You just indisputably know you do not want to be an unhappy writer. Maybe.

+

6.

Change the book’s title to another one-word title. It doesn’t help. Keep changing the title until you return to the original one-word title. You are conceding something. What that something is, you don’t know. You do not want to know.

+

7.

With an electric urgency, write the first hundred pages of the book with suspicious ease. Stand behind a creaky podium you bought at a garage sale that whines when you lean on it and read selections of the book to your dog. She walks out of the room a few sentences in. You don’t blame her. Now, shed yourself of your false modesty, muster up the most irritating arrogance you are capable of fabricating, and reconsider the book. Maybe the book will be better when unburdened by your debilitating doubts. You depressingly, predictably feel the same. Assume you must get to the end to arrive at your most accurate assessment of the book. Look for an essay by a famous writer who said that she doesn’t know what she truly thinks of a book until she writes the last sentence. You can’t find it. It may have never existed. The lies we conjure up when steeped in desperation. They work as long as we don’t discover they’re lies. You learn from this mistake, but, in many ways, it’s too late.

+

8.

Don’t show the book to anyone else. Tell people it’s because you want to protect the book while it’s being written, but you finished writing it long ago. Yet, somehow, you are still adding more pages to it. You have a hard time even showing the book to yourself. Continue printing new chapters on expensive paper. Find a new kind of paper that is so elegantly inflexible your printer constantly gets jammed. Search for a better printer and buy it. All of this distracts you from the book and how disappointing it is. The printer is heavier than god and whirrs at odd hours during the day. You want the printer to know the important work it is doing. Printing pages of such an important book and everything.

+

9.

You don’t ever want to write a book like this again. The book isn’t bad, it’s just unreadable. It scares you to think that this was the point the entire time. You were writing a book that spits out the reader. That spits out the writer. You don’t feel like a writer, and that isn’t an entirely bad thing. Yet, what is entirely bad is that you do not know how to write a book. But you are nice to strangers. That must count for something.

+

10.

No, no, it might be something else altogether. The book isn’t bad, you just don’t know how to make it good. That’s it. A small difference maybe, but, like a cracked door that was once double-bolted, it’s enough to invite you in. But you don’t realize this now. Years later, you will, when the future is no longer just a receptacle for your impatience and dissatisfaction. When the idea of an important book is replaced with the idea of an “important” book. Air quotes mediate the seriousness of “everything.”

+

11.

After writing four hundred pages, share the book with a good friend. She likes the book, and you admire her for seeing past its flaws. She is better than you. Capable of seeing what is good in it and amplifying it. There’s a kindness there that you don’t have access to. You could make it better, but the “you” required to make it better doesn’t yet exist. You worry that this “you” existed in the distant past. The “you” that awaits you in the near future will always look for this ingenious “you” that existed in the distant past. The “you” that exists right now, he barely exists. You are very confused.

+

12.

Leave the podium out on the corner of a street. No one takes it. Two boys on skateboards stop and look at it. One of them starts banging his hands against it as if it were a bongo drum. The other boy laughs. At least someone is getting some pleasure out of this.

+

13.

Whereas you once wanted to finish the book more than you wanted to write it, now you don’t want to finish the book. You are afraid to know what you truly think of the book when you write the last sentence, as a famous writer once, maybe, said. Become addicted to approaching an elusive end rather than arriving at it. Your fingers are in the habit of moving and you concede to that habit. The words accumulate and you marvel at the word count the way you marveled at the enormous, ever-growing national debt sign in Manhattan. This comparison, depressingly, fits a little too well. The number grows but it is not a good thing.

+

14.

Nearly two years pass. These are very sad years. You quit your job to write a book you are now considering abandoning. Gain some weight and watch in debilitating horror as your girlfriend’s dog gets hit by a car. Nurse the dog back into health. It hurts you to see him limp. Limp across the room and approach him as he limps toward you. You want to make him feel better about his flaws by convincing him we all uneventfully share the same flaw. So it must not be a flaw at all but the natural state of things. You will remember this dog for a long time. He was effortlessly good.

+

15.

You want to throw the book away. It takes you nearly a year to come to this conclusion. There are good parts in the book, but they are hard to find. Sometimes you find them, but it’s a single sentence or two that seems to shed the rest of the language in an endless paragraph that luxuriously reclines across dozens of pages. Print one final copy of the book and bury it in a drawer beside old electrical cords tangled into a ball that can never be unwound. Do not even try to summon your most irritating arrogance to justify the book. You’re done with all of that. Good. You are improving. As a person, but maybe not as a writer. Fine, that’s good enough, you’ll take that.

+

16.

No more important books. You see a cat get hit by a car. It leaps up into the air after it’s struck, and leaps a few more times before resting on the ground. You run up to it and cannot stop seeing its eyes. Oozing out of its face in long gelatinous tubes. The driver is sobbing and you wait with the cat until an old woman walks out of her home. She silently picks up the cat and walks into her home. Think about putting this in a book. This is a problem, and you know it.

+

17.

In the past three years you have moved three times. You carried the book with you each time. Shoved in a box that smells like a campfire. On the side of the box, it says, “Other.” It’s not in your handwriting. How did it get there? The same can be said of the book. Someone wrote it and you do not know who did. Not you, some “other.” It scares you to think so many years were wasted on that book. Open the drawer, where the book has reached its final resting place. Press your middle finger against the first page. The book does not seem to care. Why?

+

18.

Three months pass. These months are not as sad as the previous two years, but it’s unfair to compare three months to two years. Or maybe not, maybe this is a good thing to do. To take time the way you would take a woman’s hand. There are no podiums that figure prominently in these three months of your life. Your days are filled with expensive sandwiches and brief visits to beaches where dogs race around you. Orbiting as if you were a planet.

+

19.

Take a break from reading and writing. For a few months. Start to play a soccer video game, crafting a custom-made team from the worst players around the world. The players are so excruciatingly slow, and your opponents briskly hover around your sluggish players like gnats. Play hundreds of games until your players are athletic geniuses on the field. Your team is one of the best in the world, and you take your team to a knockout championship game. To build up the excitement, fully commit to the results of the game, whatever they are. You lose. Tell yourself, it’s about the journey not the destination. Rest your head against the controller and almost cry. Then start to resent the conditions of your failure. Think about how penalty shootouts are very unfair. Not in and of itself but in video game soccer. The computer seems to know. That is so unfair. Also, unfair: spending two years writing an important book that is asking you to spend a couple of more years on it. It was a self-important book, you realize, not an important book.

+

20.

Try to write the opposite of an important book. Whatever that means. It is also disappointing. In an entirely new way. Amazing.

+

21.

Start graduate school in English Literature. You don’t have much time to write. You are too busy reading other people’s words to have time making your own. Read very thick befuddling essays about very thick befuddling literature. This is a good thing, but you don’t know it at the time. Suddenly, writing stories is the thing you are not supposed to be doing. Write early in the morning, before your first class. When your roommate asks you what you did that day, say you did nothing. His cat, who slinks into your room often to sit on your windowsill and stare at you, she knows the truth. This is the best thing to happen to your writing since that professor told you that your characters need to be less serious. “I want to see a character eat a candy bar or something,” he said. That was huge for you to hear.

+

22.

On a whim, pick up Félix Fénéon’s Novels in Three Lines. Strange how you are compelled to read a few entries when so many other texts demand your attention. You enjoyed the book when you read it years ago, although you never finished it, and now you find yourself opening it up during a pleasantly meaningless lull in the day. You don’t finish it, you don’t need to finish it. These short transmissions, these momentary bursts, they can fit them in the crevices and fissures of your life now. They were waiting for that purpose, and now you are ready. Influence, you realize, is never immediate. You read to have the resources to be influenced later. At a better time. When you aren’t trying to exploit them. When you just, simply, need them.

+

23.

Write an extremely short story on an index card. It’s three sentences long and involves a dead body in a public restroom. Hang it up on your bare wall. Stare at it every now and then. Plan on writing a thousand of them. This doesn’t feel extraordinary or important. It’s irrationally compelling and you can’t explain it. You don’t want to either. Again, I repeat, do not tell anyone you are working on this project. Your girlfriend said that one time you talked in your sleep. You said, “You are getting in the way of my project.” You sleep alone now, but you are sure that you are not saying this in your sleep. Whatever it is you are saying, you don’t need to hear it. Your waking life is worth paying attention to now. For the first time in years.

+

24.

Think about some novels you loved and try to recall their intricate plots. You can’t do it. You only remember particular lines. For instance, The Morgesons by Elizabeth Stoddard. You worshipped that book but you don’t remember any of it. Faintly recall the first half of the antepenultimate line. Pick up a copy of the book and read it out loud: “When he sprang from his bed, staggered backwards and fell dead, we clung together with faint hearts, and mutely questioned each other…” It rises up from the rest of the book and hovers over it like a halo. Like a small sliver that sings down to the rest of the book. Like an epitaph on a tombstone that encapsulates an entire life. Like, like, like.

+

25.

You have a terrible memory, you’ve always had a terrible memory. Suddenly, that seems like a virtue. It’s good to know that stories have smaller stories within them, and the smallest one is the one that stays with you. You want to write those stories and make it seem as if the rest of the story was redacted. To offer up what seems left behind. The remainder of a bigger thing that grows more invisible with time. Dissipates into its elemental parts to generate blind energy.

+

26.

Write Stoddard’s sentence at the top of a notebook. You have a title. It’s the opposite of a one-word title. It’s so long, you frequently forget entire clauses of the sentence, but you know it better than you know most other things. You want to take advantage of titles. They’re not a heavy space for the author to impose an umbrella intent over the rest of the work. They’re just a modest space for another story. You also like how they are not your words. This is not about you. It is not about you writing an important book. You don’t find a trace of yourself in it. You like using the second person more now for the same reason.

+

27.

You always had a problem writing too much. Case and point: that novel with long sentences and long paragraphs that you finally threw out. You tend to write a sentence and find a dozen more in them. That has to stop. That’s not to say this kind of writing is not enjoyable, you just know that it’s not what moves you forward. It’s a way back into something that fools you into thinking it’s a way forward.

+

28.

Buy a dip pen and an inkwell. Nearly a decade ago, you used a dip pen to draw frantic abstract images on fine bristol paper. Electrical currents passing through amoebic shapes. Littering the space like graffiti. Some images had a dark line slashing the space like a knife. It was a way to move your hand without writing any real language. It was a liberation that was unburdened by accomplishment and ambition. You slipped those sketches in a folder and hid them. They’re at the bottom of a box filled with rusted kitchen utensils. You do not throw out the sketches for the same reason you do not throw out the rusted kitchen utensils.

+

29.

The sharp nib of the dip pen, shaped like a thorn torn from a rose, is finicky. It oftentimes snags on the textured parts of the page for a moment then skips abruptly, splashing some ink on the page. Leaving a constellation of orphaned periods, untethered from unwritten sentences. You can only write a few words at a time before the pooled ink in the nib runs out and you have to dip the pen back in the inkwell. You also buy a waterproof notebook that only accepts pencils and ballpoint pens. All other pens cannot leave a mark on the paper. Dip pens with thick india ink seem to register, although it takes a frustratingly long time to dry. You have finally found an excessively elaborate way to slow down your writing. To make it as inconvenient as possible. Do not tell anyone you do this. Maybe tell people only when the book is far behind you. A distant, nearly-invisible memory that you can’t change anymore.

+

30.

During classes in graduate school, pull words from the academic conversation like a child with a jar and fireflies. Words that compel you without explanation. Write them down in the margins of your notebook. Put them in small groups that seem to form constellations, a bare architecture for a story that is, itself, a bare architecture for a bigger story. “Profit,” for instance, seems to work with “color.” You go home and write, “The color of profit.” It isn’t a very good story, but who cares. Done. Next.

+

31.

Start to get obsessed with aphorisms, maxims. Read the aphorisms of La Rochefoucauld, the notebooks of Joseph Joubert, the work of Jenny Holzer. Open books randomly and read a sentence as if it were an aphorism. Suddenly see aphorisms everywhere. Flippantly open a book randomly, close your eyes, and snake your finger across the page for a while then stop. The finger is pointing to a single word. There’s an aphorism. Right there. Why not.

+

32.

The smallest things suddenly have abundant meaning. Read more than you write. Start to worry about writing a single story rather than a book. These might be fragments, but you don’t think of them as such. You don’t know what to think of them. You try not to think of them. Do not think, do not think, do not think. Not thinking of them makes them feel pure. Untainted by your ambitions. By your awkward, heavy psychology.

+

33.

Devise more methods to help generate these stories, although your future self will not remember all of them. Remember: you have a terrible memory. Like a little machine, each method generates dozens of stories before breaking down. You build up a new machine, maybe using a few spare parts from the machine that broke down, and generate more stories. You are building and breaking, over and over again. And it is an absolute pleasure, if a bit strange. No, it is an absolute pleasure because it is very strange.

+

34.

The book seems unpublishable. You don’t care. No, that’s not true. Instead, it doesn’t bother you enough to stop you from writing the book. You want to write a book that would dissipate easily into the ether. It is, in a way, unfinished business to do this. You always had a fantasy of writing a book and throwing it in a fire. One time you wrote a book of poems called Youth. Each poem was titled, “Youth,” and you slipped them in an envelope and threw them in a box. But, in the end, you submitted a few to magazines. One time you bought a zen garden and wrote lines for poems in the sand and raked them out. But, in the end, you memorized a few lines and slipped them into a story you were working on. Buy a small black pouch at an art store and slip the notebooks of aphorisms, maxims, stories in there. You don’t feel like you are throwing away the book, you just feel like you are hiding it away from yourself and your putrid ambitions.

+

35.

You oftentimes forget the stories you wrote the previous day. Be convinced that those are the best stories because you don’t feel as if you wrote them. Barely re-read the old stories because you want them to miraculously disappear. With enough time, they will, and they will be good. Move faster and faster. The quicker you move, the easier it is to forget.

+

36.

You want to write the book as briskly as possible. Two or three months and that’s it. You want it to happen without realizing it happened. You want to make it into something that resembles what you pull out when you try to remember something with your terrible memory. When your roommate is at his girlfriend’s house, you read the stories to his cat. She sits patiently and falls asleep. You keep reading the stories to her sleeping self. There’s something abundantly appropriate about this, you think.

+

37.

Befriend someone who makes guacamole constantly, impulsively. Start to enjoy guacamole. It is very good now. You are changing. The guacamole represents something bigger. You don’t know how big, but it’s bigger than you, and that is a good thing. Also, good: it is big enough to invite you in. And when you are in it, you are such a liberatingly small part of it. So much so you don’t feel as if you are in anything.

+

38.

You finish the book very quickly and celebrate by buying yourself a vanilla shake. Walk around in the dark sipping on your vanilla shake. Come home and share the news with your roommates’ cat as she stares out the window. A crow hopping toward several stale bagels. Earlier that day, you flung them out like frisbees while standing shirtless on your deck. Slip the four notebooks in a drawer with the dip pen and inkwell. This isn’t an important book. It is an anthology of infinitesimal confusions that collaborate into a momentary urge you inexplicably had.

+

39.

Six months pass like six months. Periodically recall writing a book of hundreds of stories and wonder if you in fact did that. Pull the four notebooks out of the drawer and read the stories that you don’t remember writing. Pull out a stack of papers from another drawer and read the novel with the one-word title that you don’t want to remember writing. Forgive the “you” that existed in the distant past. The “you” that wrote an endless novel and looked for another “you” that never came. Realize that “you” is you. Begin writing a new book and make amends with the perpetual failure that hibernates in the space between each word you write. These things happen. That I make them happen, you think, that is something good. An innovative idea of failure that makes you move forward.

+

40.

A year later, show a few of the stories to a friend. She tells you it is unpublishable and you genuinely don’t care. When you were six, you fell on your face in a dark hallway, sprang up, and sprinted home. Think back on that memory the same way you think of that book. It is good in that new and old way. You wrote it to see what you could do if obsession smothered ambition and left you with the most preliminary desires. The kind of desire that got you writing in the first place. You wrote your first essay in college when your mother was rushed to the emergency room. You closed your eyes and wrote the thing without ever looking at the computer screen. You tried to do that with this book of extremely brief stories. What it is now does not matter as much as what you did to make it. That is something that you tell people. Say to them, in so many words, that you wrote this to write without any self to buttress its value. Say to them, in so many words, that if the book is boring or befuddling to others, then you are okay with that. They ask you if you will send it out. Say to them, “I’ll send it out when I’m ready to let it go.”

+++