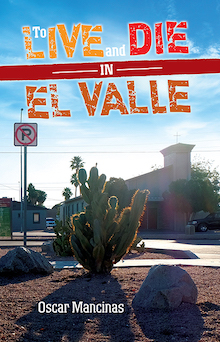

Our Research Notes series invites authors to describe their process for a recent book, with “research” defined as broadly as they like. This week, Oscar Mancinas writes about To Live And Die In El Valle from Arte Publico Press.

+

El Precio del Pasaje

The opening scene of the 1991 documentary Hearts of Darkness: A Filmmaker’s Apocalypse finds Francis Ford Coppola remarking on the weight and meaning of his 1979 Vietnam War movie Apocalypse Now. “My movie is not about Vietnam,” Coppola tells the audience, “my movie is Vietnam.” You wouldn’t be faulted for objecting to Coppola’s comparison between the destructive U.S. military invasion and occupation of Vietnam and his troubled production of a film based on Joseph Conrad’s Heart of Darkness, but, then, that’s why it’s worth watching the documentary. Whether this opening line is empty hyperbole or vital insight into Coppola’s eccentric stubbornness is ultimately up to the viewer to determine. At any rate, I cite this line, with this explainer, to offer the following observation about my own recently released work.

The opening scene of the 1991 documentary Hearts of Darkness: A Filmmaker’s Apocalypse finds Francis Ford Coppola remarking on the weight and meaning of his 1979 Vietnam War movie Apocalypse Now. “My movie is not about Vietnam,” Coppola tells the audience, “my movie is Vietnam.” You wouldn’t be faulted for objecting to Coppola’s comparison between the destructive U.S. military invasion and occupation of Vietnam and his troubled production of a film based on Joseph Conrad’s Heart of Darkness, but, then, that’s why it’s worth watching the documentary. Whether this opening line is empty hyperbole or vital insight into Coppola’s eccentric stubbornness is ultimately up to the viewer to determine. At any rate, I cite this line, with this explainer, to offer the following observation about my own recently released work.

My collection of short fiction, To Live and Die in El Valle, is not about Mexican and Indigenous people pushed to make painful exchanges and compromises in hostile settings, it is a series of painful exchanges and compromises made by me, a Mexican-Indigenous person in hostile settings. This isn’t to frame myself, nor others, solely as victims — helpless, inert, bereft of hope. Never. Rather, I mean to clarify some of the material realities of writing, editing, and publishing stories from and about communities marginalized by colonialism, capitalism, racism, and policing.

For example, I never could’ve written, edited, and published short stories about my home without leaving. Arguably, everybody has to “leave home” to broaden their views or pursue opportunities and challenges, but when I talk about leaving home, I’m talking deliberately about the ongoing European and Euro-American practices and policies of exclusion and extraction, which make it nearly impossible for people to live, let alone to create literarily. My dad’s family had to leave behind our Indigenous homeland, and eventually he had to abandon his adopted home, too, because of economic necessity; my mom’s grandfather got conscripted into being a migrant laborer in Mesa, Arizona, of all places, triggering generations of consistent, if unstable, movement back-and-forth between Mexico and my birthplace. By comparison, you could say my road was less painful, if only politically and linguistically. Thank you, birthright citizenship and TV!

These kinds of exchanges aren’t the beginnings nor ends of our stories. Migration, movement, and displacement don’t define us, but they’re also more than moral trials or challenges placed before us so that we may prove our ultimate goodness to ourselves — or, worse, to others. Depending on how I approach them, then, they are setting, character, inciting incidents, causes, consequences, and imperfect resolutions. If this sounds contradictory, welcome to one of the central tensions in my life and within the kinds of things I try to write.

Intrinsic to this tension, additionally, are questions of audience. After all, context and explanation deemed “necessary” has everything to do with what I believe my readers: 1) already know, and 2) must be presented, so they understand where I’m headed. I can’t speak for other linguistic experiences, but any writer who’s ever written some Spanish description and dialogue into a story presented to a workshop of monolingual English peers has heard the same critiques: Does this need to be in Spanish? Won’t it alienate the reader? Never mind, of course, that 99% of the piece in question is in English. Ironically, I’ve encountered similar critiques from bilingual English-Spanish readers when they encounter Rarámuri words I’ve written into some pieces, ¡pero eso será un tema para otra polémica!

These kinds of workshop critiques can be annoying or insulting, but I think they raise legitimate questions about author intention. While the critiques project the prejudices of a mythical universal reader — one who not only doesn’t understand Spanish or Spanglish but will go so far as to outright quit a text should an author write in anything but the king’s — they nevertheless force us to reflect upon for whom we are writing and why. Clarifying who I desired to find and read my stories helped me to determine what kinds of details, descriptions, and dialogue felt necessary. I wrote with my home in mind, thinking of people who live here and those who will live here in the future; I hoped they’d be excited by familiar vernaculars and settings and yet willing to expand their views to try to understand anything that didn’t seem immediately recognizable, comfortable.

In exchange for writing toward my intended readers, other readers — those who arrive as outsiders and decide it’s worthwhile to decipher what feels new or different within my work — would become fortunate bonuses. I know some of my best, most fun reading experiences involved me immersing myself in worlds which bore little resemblance to my life but managed to teach me something essential about the universe — or, at the very least, took me on a ride and encouraged me to dream. I hope To Live and Die in El Valle provides one or more of these types of reading experiences: smile at the familiar, contend with discomfort, and try to make it all fit within a comprehensive, if conflicting, understanding of the world.

No doubt, many will reach this paragraph and realize I’ve said little, save for “it’s difficult to fight for and achieve literary equity when you’re brown-skinned, working-class, migrant, Indigenous, Spanish-speaking… and, at the same time, it’s important to think about audience.” As someone now on the other side of the published-a-book experience, I wish I had something more profound to offer regarding the process. Then again, why try to reduce writing, rewriting, revision, and editing to transaction — lessons earned for years of work? This is neither the beginning nor the end, only a chance to catch my breath and to keep going. Ándale, pues.

+++