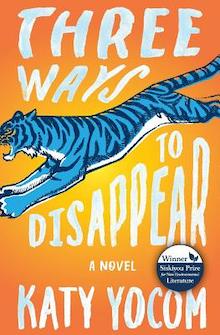

Our Research Notes series invites authors to describe their process for a recent book, with “research” defined as broadly as they like. This week, Katy Yocom writes about Three Ways to Disappear from Ashland Creek Press.

+

Fall in love with a litter of tiger cubs born at your city’s zoo. Develop an obsession. Follow it, even though it makes no sense. Understand that your life is going to change. Fail to understand why. Fail to care that you don’t understand why.

Fall in love with a litter of tiger cubs born at your city’s zoo. Develop an obsession. Follow it, even though it makes no sense. Understand that your life is going to change. Fail to understand why. Fail to care that you don’t understand why.

Find the joy in it. Watch the cubs with rapt attention; absorb their features until you can tell the three of them apart. Stand at the window gazing upon them for thirty minutes, an hour at a time. Try to visit when the viewing area won’t be crowded with children in strollers. Realize you’re one of the few adults at the zoo not pushing a stroller. Fail to care. Parents and children come through, look, and move on, but you don’t go to the other enclosures. You don’t visit the other animals. You have eyes only for the tigers. Half an hour in their presence leaves you replete.

There is something holy in all this.

The five steps of lectio divina: Read. Pray. Meditate. Contemplate. Act.

Read the tiger as a text. Gaze at the animals as if careful observation will create space for some kind of transcendence. Memorize the thickness of their legs, the size and shape of the white spots on the backs of their ears, the pattern of their stripes. When the triplets are small and fuzzy as stuffed animals, watch the female cub climb shakily onto a log, balance there for a moment, then fall into the sawdust, executing a solid face plant. Watch her raise her surprised face and shake it off.

Engage in a conversation with the universe about the inexplicable charisma of certain top predators. Consider that beauty is a value of nature for its own sake. Consider that in the wild, only the most vigorous specimens survive, which means the vector is toward flawlessness. Believe that there is no shape, no color pattern, no assemblage of features more beautiful than the face of a tiger.

Meditate upon the spiritual reality of these great creatures: tigers as immanence. Remember Christopher Smart, imprisoned as a madman in 18th-century London, writing about his cat Jeoffry:

For he is the servant of the Living God duly and daily serving him.

For at the first glance of the glory of God in the East he worships in his way.

For this is done by wreathing his body seven times round with elegant quickness.

For then he leaps up to catch the musk, which is the blessing of God upon his prayer.

For he rolls upon prank to work it in.

(He rolls to work the blessing into his body!)

Note the depth and clarity of Smart’s observations, the humility of his authorial stance, the deep joy of his homage. All this from his asylum cell.

Dive deeper into your obsession. Read books by naturalists and confront the fact that the wild tiger’s time on earth seems to be reaching its end. Grieve the genocide to which tigers are still being subjected: 96 percent of the global population eradicated since the turn of the 20th-century. Mourn their slaughter for sport and profit even as they figure into the realm of the divine. Encounter tales of Dakshin Rai, the Tiger God of the Sundarbans, worshipped in that watery land by people of every religion, and therefore, in his way, above religion. Learn of Durga, the fierce protective mother goddess of the Hindu pantheon, who rides a tiger. Contemplate the statistic cited by the World Wildlife Fund: that to save one tiger, you must protect 25,000 acres of land, and in sheltering that land, you protect all the creatures living in it, the trees that dine on sunlight and exhale pure air, the waters that course through that territory.

Confront the fact that impoverished farmers living near tiger reserves have no choice but to compete with the great cats for resources. Admit that defending the land means declaring it off limits to people who have no other way to live. Begin to understand that to save the tiger from extinction requires ending systemic poverty.

Fear this knowledge.

Begin writing.

Begin writing a novel that will explore questions too outsized to answer. Feel those questions out there waiting for you like a tiger in the night, a tiger the size of a house, crouching hidden in the forest with his mouth open, waiting for you to blunder in. Scare yourself with the enormity of what you’re taking on.

Write until you realize you don’t have what it takes to keep going. Or rather, you don’t have it yet. Accept with noetic certainty that your obsession requires you to seek out tigers in the wild. Plan your itinerary, book your plane ticket, go. Arrive in India the day a front sweeps down from the Himalayas, bearing Northern India’s coldest temperatures in 70 years. This is auspicious: The chill brings animals out of hiding, such that you spot tigers in the wild nearly every day of your trip. In a haze of golden afternoon sunlight, observe a tigress resting at a lakeshore, seemingly aware of her splendor as the water reflects her image.

On an overnight train between Jabalpur and Kolkata, find yourself uncertain how to answer when a businessman/spiritualist in your compartment asks how you came to be obsessed with tigers. Begin by saying, “A litter of cubs was born at our zoo.” As the words leave your mouth, hear the ordinariness of that statement. Thousands of people have seen those cubs and come away unchanged, while you? You traveled 8,000 miles and ended up here, shuttling between tiger reserves on this train, sharing a sleeper compartment with a businessman/spiritualist from Mumbai. Listen to your voice trail off, giving way to the thrum of the rails, the black of night outside the window.

“Passion,” the businessman/spiritualist says. “You can explain to yourself how you came to be passionate about something, but you can never explain why.”

The train rushes through the Indian night.

“It’s just as good to go chasing after tigers,” he adds, “as it is to go chasing after God.”

Feel a space open up, a gap that admits and accepts the possibility of mystery. Recognize that if this is all you ever understand of your obsession, it is enough.

+++