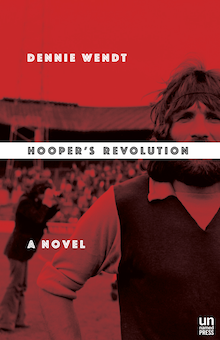

Our Research Notes series invites authors to describe their process for a recent book, with “research” defined as broadly as they like. This week, Dennie Wendt writes about Hooper’s Revolution from Unnamed Press.

+

Kicked Off,

How Hooper’s Revolution Came To Be

This book is the direct result of rejection.

I had written an absurdist novel about corporate life and brand marketing that I’m not entirely sure the world needed, but I thought it was pretty good. It was good enough to reach a big-hitter New York agent who thought long and hard about taking it on (I think she thought long and hard about it anyway) before declining. She thought the writing was good, but the story just didn’t quite work for her. I was crushed. I’m not often crushed by rejection anymore — there have just been so many. But I really thought I might break through this time. She told me she’d be interested in reading my next novel. “My next novel?” I said to my wife — “my next novel? That will take at least two years…I don’t even have an idea. This agent’s not going to remember me in two years.”

I had written an absurdist novel about corporate life and brand marketing that I’m not entirely sure the world needed, but I thought it was pretty good. It was good enough to reach a big-hitter New York agent who thought long and hard about taking it on (I think she thought long and hard about it anyway) before declining. She thought the writing was good, but the story just didn’t quite work for her. I was crushed. I’m not often crushed by rejection anymore — there have just been so many. But I really thought I might break through this time. She told me she’d be interested in reading my next novel. “My next novel?” I said to my wife — “my next novel? That will take at least two years…I don’t even have an idea. This agent’s not going to remember me in two years.”

Fortunately, one of us was in an optimistic mood.

“Come on,” she said. “There’s got to be an idea in there somewhere.”

“Not right now there isn’t.”

“Isn’t there something you know better than anyone else? Some subject you could just sit down and start writing about right now?”

Well, there was, and is, but before we get there…

Hooper’s Revolution is my fourth attempt at publishing a novel. Like most novelists, if I’d kept every rejection letter or email from agents and editors, I could wallpaper any room in my house and have leftovers. My first attempt, which I wrote in the year or two after college, was an embarrassingly autobiographical campus novel that got me an agent (for a while) but — fortunately — never quite found a publisher. It has its moments; I guess I see what the agent saw, and most of its rejections seemed to think I could write but just hadn’t really built a story worth caring about. A few accused me (nicely) of ripping off people I hadn’t even heard of, though when I looked them up I was flattered. In my late 20s I wrote a baseball novel, which I still think was publishable and at least somewhat entertaining and which very nearly saw the light of day. It was about a lunatic entrepreneur/failed political candidate who duped a cadre of businessmen into funding an indoor baseball league. It was inspired by a couple of summers I spent working for a professional indoor soccer team in Portland, Oregon, but that was the ’90s — no one read soccer books back then — so I just converted soccer stories to baseball stories. It got close — really close. But now I had a job, a family, a non-novelist’s life. The rejections didn’t hurt as much. There had just been so many of them.

I took some time off, focused my energy on work, moved from Oregon to Massachusetts. I missed writing fiction, but more the way one misses high school than the way you miss a friend: I had good memories, but it’s not like I needed to go back. Still, I never got out of the habit of seeing great characters and stories in my everyday life; I’m not sure truth is stranger than fiction, but I think I can say that slightly falsified truth — if you’re around the right people — is usually about all the fiction you’ll need. And so I wrote Brand Plan.

It’s a good book. Has some problems, and someday I’ll fix them, but it’s a fun read. Anyone who has ever worked in a marketing environment with mercurial but brilliant people, which is probably a lot of America, will identify with its desperate strivers, messianic capitalists, and the otherwise normal human beings who trail in their wake. Of course, I’m not sure that makes it necessary. For years, I couldn’t watch The Office — I lived something to similar to it. It just wasn’t funny to me. So if a moderately amusing, stress-inducing office novel doesn’t do any good for the people who might identify with it, well then…

Anyway, it suffered its own raft of rejections. But the letters and emails were much more polite, and more specific — I was getting insightful commentary on the characters and the story arc, and the agent, the one in New York — Brooklyn even — thought she might take it on.

Until she declined. And now I had to write something. Quick. Before she forgot who I was.

“Well,” I told my wife, “I’ve always had an idea, more for a long article than a novel, about the English soccer players who came over here in the ’70s, kind of a fish-out-of-water story. I’d like to go over there, find a few of them, ask what it was like. I loved those guys.”

“OK,” she said. “Let’s make that fiction instead of non-fiction. Now we need a hero. Who was the hero of ’70s soccer?”

Easy. “Pele.”

“Now we need a villain. A good ’70s villain.”

“Well, that would be Russia. The USSR.”

“Yes! Perfect. Now go mix an Englishman into that story and I think you’ve got something.”

I nodded and rubbed my chin. My brain was already putting it together. People do read soccer books now, I thought. “This could work,” I said. “I’ll do it.”

She said, “Go do it right now. Like, right now. Go start.”

So I did. Sat right down at my desk that very evening and made up a character named Danny Hooper, an amalgam of every Englishman I loved watching in those days. And I made up some crazy reason he got sent from England to Oregon to play (I’d moved back to Portland by now — a soccer book sent in the heart of Portlandia… perfect) and, ultimately, to save the life of the world’s most precious footballer, a certain beloved and entirely magical Brazilian. I tried to capture the greatness of America soccer from that era, when many of the world’s best players came over here to wind down their careers, play in the sunshine and make a few bucks. And I tried to offer the story some ’70s ridiculousness. Something to really tickle soccer snobs and entertain the casual sports fan. It builds to a “Black Sunday”-like finish. Whenever I tell people it has scary Russians, they congratulate me on my timing.

I finished a draft in three or four months. Took another year to polish it. Dug around for publishers, editors, agents who seemed to be people like me, taking care to avoid submitting to anyone with pedantic font and margin requirements — I’m now deep into my 40s; I just know that those aren’t my kind of people. I suffered another barrage of rejections from editors and agents both, including a thoughtful regret from that nice agent in Brooklyn who liked it but just wasn’t sure she could get behind a soccer book. A small press in New Jersey liked the book quite a bit and e-mailed me that Hooper’s Revolution on was on their short list for the coming year. When they finally declined, I was devastated. I didn’t think I had it in me anymore. I didn’t think I cared quite that much.

I still don’t remember how I first heard of Unnamed Press in Los Angeles, but I remember reading an article about them somewhere. Something in it told me they saw the world as I did — something in their humor, their interest in stories off the beaten path and in “new voices.” I submitted Hooper’s Revolution to Unnamed and did what I usually do: tried to forget about it. Weeks passed, as they always do, and then one Friday afternoon, I checked my email for one last time before giving the weekend some serious thought and saw an email from C.P. Heiser, editor at Unnamed. It featured two words I had never seen from an editor ever:

“Call me.”

+++