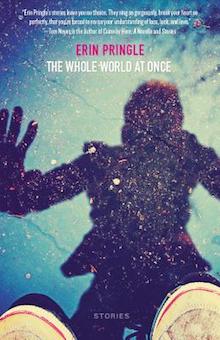

Our Research Notes series invites authors to describe their process for a recent book, with “research” defined as broadly as they like. This week, Erin Pringle writes about The Whole World at Once from Vandalia Press.

+

Notes on Grief while Writing Fiction

I wrote and revised most of the stories in The Whole World at Once in various stages of mourning, a decade after my father’s death, during my best friend’s death and a few years later, my sister’s. So, in that process, I struggled a lot understanding a world that did not follow the rules it’s supposed to in fiction.

I wrote and revised most of the stories in The Whole World at Once in various stages of mourning, a decade after my father’s death, during my best friend’s death and a few years later, my sister’s. So, in that process, I struggled a lot understanding a world that did not follow the rules it’s supposed to in fiction.

In grief, there’s no epiphany. There’s no purposeful lack of epiphany. There’s conflict, which is death, but that can’t be resolved. So, there’s no rising action. No sage. No hunter come to save the girl in red, and no way to save oneself no matter how clever you are. Moving through the day has a surreal edge to it. I remember thinking, in deep mourning, and still do when a wave of grief captures me again, Of course the surrealists painted as they did! A melting watch? Absolutely a melting watch. Who can even paint a non-melting watch? Of course the absurdists wrote those plays! Of course Martha & George mourn an imaginary son. That’s exactly right. That’s not absurd at all. Because in grief, you’re moving through a world that does not abide by rules. People crouch in grocery aisle, comparing the prices of name brand cookies to generic cookies, at the exact same time that my sister is being buried in a hole by a train track. How can that be? How can my best friend be diagnosed with a fatal disease and a tube slid into her body? How is it that I couldn’t become a doctor and save her life? How can it be that my father’s still dead and it’s Monday again? It all feels ridiculous and impossible. And yet.

So, these are questions that I ask in the stories, or these questions are allowed to exist in the world my characters find themselves in. I think the kind of steadiness that exists in much of contemporary literary fiction requires a steady life, and I haven’t had that life, or the illusion of it. Story, I was once told, is the day unlike any other day. But! If conflict is constant, struggle daily, then the day like any other day is the story. To have a calm day would have to become the “conflict.” But that’s hard to write. I’ve tried to. So these are stories after loss. The stories are not the losing, not the hopeful attempt to save what’s about to be lost. It’s already gone. And that’s the difficulty, the conflict. The inability to stop, to save, to rewind. From “The Lightning Tree,” in which a spouse wishes he could save his wife from dying, to “The Sun Burns Among Rocks and Pebble,” in which a little sister is no longer searching for her missing sister, found dead, but the girl’s grief is still there and sparked by her encounter with a carnival worker.

Maybe this isn’t common, but for a very long time, I thought everyone was having the same experiences as me, so I’ve just been angry that no one has been telling the truth about sadness and grief. Even though it was clear that not everyone was driving to and from funerals, to and from hospitals, but when I was in deep grief, those people were the only ones I focused on. The ones who must also be in deep grief. But, recently, my life has become steady for the first time, and so now I’m having new thoughts, like, Oh! When you’re not struggling to pay bills or when you’re not fighting depression or when you’re not nearing the two year, three year, sixth year anniversary of your sister’s death, you do have ordinary days in which you do have sort of realizations about the world. Maybe because the world is made to make sense when loss isn’t happening. So, maybe everyone hasn’t been lying after all. Maybe sad stories just come from sadness, and steady stories from steadiness. For a long time, I’ve felt apologetic for writing sad stories. Like I was supposed to be writing happy stories. What do you write about? Oh, mainly sad stories. Then there’s this silence.

Our everyday language isn’t made for talking about sadness with strangers. So, it’s hard to talk about my book to people without making them or myself feel uncomfortable. Death’s uncomfortable. Sadness is, too. At least in this culture. Which is what makes mourning so surreal. Because no one knows how to talk about it, what it means, especially if you don’t believe in god or have the language of ritual to help the conversation. The stories in The Whole World at Once try to create the language that can communicate loss, awkwardness, humor without making anyone feel wrong or strange. That’s my intention, anyway.

Recently, my life has become steady in a way it has never been, and so that’s what my newest stories revolve around. What it means to fall in love after so much loss. It feels selfish and rude. Especially because I like being in love. I don’t know if I should enjoy it. Does someone earn enjoying love? Should I pretend it’s not happening? Am I really in love or just delusional? Is this a new stage of mourning no one told me about? I also have a child now, and I really like having this child who laughs and wears glittery shoes. Did I earn him somehow, because I had a miscarriage first? What about all the women who are having miscarriages right now? What is my life’s relationship to their lives? I want to kiss all of them. I want to tell them, You hurt. Of course you hurt. I’ve watched hope bleed out in the bathtub, too.

I don’t know how to save anyone, and I have so many questions. This life. Jesus, this life.

The closest I’ve come to people and to having answers is in the act of creating fiction. I didn’t intend to write fiction that would break anyone’s heart. It’s just that my heart kept breaking for about 20 years, so this is the fiction I’ve been writing. I hope my next book can give more promises, have some love in it. It seems like a worthy project. And if I’m lucky to be in love for longer, lucky to be with this wonderful child for longer, it will be. I hope so. I hope loss stays away, at least for one book. But I’m proud of the stories in The Whole World at Once and proud of the characters for allowing grief to be as beautiful as it is hard, and letting readers watch it all while living their own beautiful, hard lives.

+++