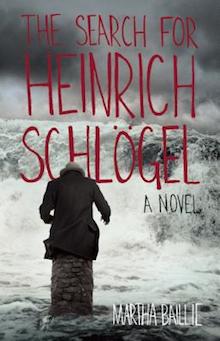

Our Research Notes series invites authors to describe their research for a recent book, with “research” defined as broadly as they like. This week, Martha Baillie writes about The Search for Heinrich Schlögel from Tin House Books.

+

I wanted to research the life of Heinrich Schlögel but he did not yet exist. Eager to know him, almost desperate to do so, I imagined what books he might have read. Suddenly, it was as if he’d invited me into his bedroom. Several books were lying on his bed, another few on his desk and one on the floor. Apparently, he loved to read about animals.

I wanted to research the life of Heinrich Schlögel but he did not yet exist. Eager to know him, almost desperate to do so, I imagined what books he might have read. Suddenly, it was as if he’d invited me into his bedroom. Several books were lying on his bed, another few on his desk and one on the floor. Apparently, he loved to read about animals.

Too lazy to go to the nearest public library to look for the books I’d seen in Heinrich’s room, instead I gleaned information about animals and birds from the Internet then invented books for these gathered facts to inhabit. Each conjured volume required and received a title: Raach’s Illustrated Birds of the World, A Visual Tour of the Paris Museum of Natural History, Amazing Mammals of the Deep. Slowly, borrowing and savouring passages about the abilities of moles, hedgehogs, butterflies, blue jays, and whales, I was coming to know Heinrich.

The whale does not use its ears for most of its hearing but its lower lip, which is tapered and allows a more focused collection of information in the form of sound waves. This data travels from the back of the lip to the inner ear by means of a string. The sound waves that enter by the ear are too diffuse to allow the whale to form the precise pictures that constitute its principal source of vision. In matters of seeing, the whale relies even less on its eyes than its ears, and would be ostensibly blind were it not for its lower lip.

— Amazing Mammals of the Deep

I knew for certain that Heinrich had an older sister. What she looked like I couldn’t say, but I could hear her voice quite clearly. If I listened hard enough, might her face come into focus? She had a talent for languages and was studying Inuktitut. While she closed her bedroom door and concentrated on a voice released from a cassette tape, a voice repeating lists of words, I located free Inuktitut lessons on the Internet. Because Heinrich, hovering outside her bedroom door, distracted Inge from her studying, she gave him the diary of Samuel Hearne to read. Quickly, I ordered Hearne’s diary from the public library and read it cover to cover. In Hearne, the first European to journey overland, across northern Canada to the Arctic Ocean, Heinrich found a hero. Like Hearne, Heinrich was good at walking.

It was now clear that I had no choice but to go for a long walk in the Arctic. I invited a friend. We chose a wilderness park in Baffin Island. Auyuittuq Park. We would hike not for months but weeks. Including two guides, our “expedition” would consist of nine people. From Pangnirtung a boat carried us the length of a fjord. At the mouth of the Weasel River, we jumped ashore, swung our packs on to our backs and began to walk. The river twisted and the valley twisted with it.

The sound of water is constant. The glaciers only appear to be motionless. Their silence is untrue. They speak in ropes of blue water. When the water reaches the edge, it falls straight down the mountainside, crashes whitely, plunges farther, lower, babbles, soft-edged at last, between mossy, flowering banks; it spreads out over vast beds of gravel. As for the weasel river, I walk beside its green and milky width but cannot hear it flowing, my ears full of the roaring mountainside.

— The Search for Heinrich Schlögel

+

The land had much to communicate. There were times when he allowed its vastness to reach a scouring hand inside him. But its details, the stories it articulated, he couldn’t read. He’d become illiterate.

— The Search for Heinrich Schlögel

In this text, I’m imposing an order upon my past research. Words elicit order. One sentence leads to another and events acquire a chronology. Important moments, fall into crevices and vanish; they fail to stake their claim within the shifting narrative: A trip by train from Paris to Freiburg then by car to Tettnang, in the dead of winter, the view of the mountains eclipsed by whirling snow, the apple trees bare, the Hops Museum closed. We drove in circles looking for Heinrich’s house. Locating the butcher shop, the castle, and the school was easy, as these he’d included in the map he’d drawn of the small town of his birth. His house figured also in his quick sketch, but he’d neglected to indicate a street number.

The research that truly matters, in my experience, rarely occurs in a predictable or timely manner. Answers, impossible to find, arrive of their own accord or don’t.

Over a period of years I stumbled in and out of public art galleries. Suddenly, Brian Jungen’s immense skeleton of a whale, made from white, plastic garden chairs, hung above my head. It cast graceful shadows on the floor. In the next room stood a black teepee, made of leather recently stripped from a sofa. In another city, in another room, months later, the work of Nadia Myre surrounded me. I stepped right up to the wall, to read the posted words, printed from the Internet, and not yet entirely covered over by strings of tiny, red, and white, glass beads. Hundreds of volunteers had gathered in communities of varying sizes to form beading bees, to assist the artist in silencing the Indian Act, burying it under another language.

In Pangnirtung, dust, wind, and the rhythms of Inuktitut enveloped me. Hannah Tautuajuk invited me in, rented me a room, and showed me her collection of knives. I stayed with her a week. She showed me a kindness I won’t soon forget, and patiently answered my many questions. Together we watched television, and when the warmth of her house made me sleepy, I would step outside, into the mosquitoes, and wander down to the sea.

The river raced and frothed, down through the settlement and into the sea. The bungalows sat, as if by accident, along the broad, unpaved roads. How would Inge respond to this place? Heinrich wondered. Pale dust from the road had settled on the snowmobiles that waited for winter, in the grass between the houses. It was a place of accidents. The same dust coated the crushed pop cans, plastic bags, torn clothes, battered strollers, discarded toys, scraps of metal and old carpet lying in ditches, under back stairs, in babbling brooks of clear glacial water. Footpaths led out onto the land.”

— The Search for Heinrich Schlögel

The novel that has resulted from my research feels to me both accidental and calculated, a gift from others (some alive some dead), from animals, from the raw beauty of Baffin Island, and the very different beauty of the agricultural lands that slope down to lake Constance, a few hours’ drive from Freiburg, a few hours in a snowstorm, less under a blue sky, or so I am told.

We also suggest a visit to The Schlögel Archive.

+++