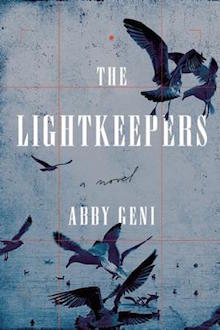

Our Research Notes series invites authors to describe their process for a recent book, with “research” defined as broadly as they like. This week, Abby Geni writes about The Lightkeepers from Counterpoint Press.

+

Mysteries and Memoirs

It began with Agatha Christie, as so many things do. In a moment of curiosity, I picked up The Murder on the Orient Express, and a few days later I read And Then There Were None. Over the month that followed, I devoured every one of Christie’s dozens and dozens of marvelous mysteries.

It began with Agatha Christie, as so many things do. In a moment of curiosity, I picked up The Murder on the Orient Express, and a few days later I read And Then There Were None. Over the month that followed, I devoured every one of Christie’s dozens and dozens of marvelous mysteries.

At the time, I didn’t know I was doing research. I was just reading for fun. A quirk of my writer brain is that when I’m actively engaged in a new project, I find it difficult to read anything in the same genre that I’m working in. Since I write literary fiction, I don’t often read literary fiction. It’s a shame, but I’ve come to accept it. I love novels, but I don’t love the feeling of another narrator’s voice in my head, another writer’s characters overlapping with mine. So I read nonfiction. I read science fiction. I read mysteries.

There’s a reason Agatha Christie is known as the Queen of Crime. The deeper I dove into her books, the more fascinated I became by their architecture. A good mystery has an exquisite economy. The story is distilled to most fundamental elements. Red herrings are placed with precision and forethought. Suspects are fleshed out to a specific degree. The reader is given exactly the right amount of information and no more. Everything that happens has to happen. The best mysteries waste no muscles.

From Christie, I moved on to Georgette Heyer, Arthur Conan Doyle, Dorothy Sayers, Ngaio Marsh, and Rex Stout. I soon realized that my favorite mysteries had a particular set of variables: an enclosed setting, a limited group of suspects, and a plethora of motives. Death in the Clouds: death, a plane, and its passengers. Behold, Here’s Poison: a death, a mansion, and its inhabitants. Murder Must Advertise: a death, an ad agency, and its employees. I did not care as much for the stories in which the suspect pool included all of London or New York. I wanted six or seven people at most. I wanted them all in the vicinity at the time of the murder. I wanted each of them to have good reason to want the victim dead. I wanted no solid alibis. To my mind, a whodunit is best when the “who” is comprised exclusively of people the reader knows well.

At the time, I had already begun writing The Lightkeepers. I was getting to know Miranda, my protagonist. I was drafting scenes from her childhood and reading up on photography, her passion. The other characters in the book had begun to take up residence in my brain as well. I was learning about their loves and hates. I was dreaming up dialogue to see how they interacted.

I am not a mystery writer. I make literary fiction — short stories and novels. I write about the natural world. In The Lightkeepers, I wanted to write about disappearance and loss, grief and recovery. I wanted to go deep into Miranda’s unusual mind, her unconventional take on the world. I knew better than to try and make a copy of Christie’s great works. I did not think or write like she did. But I could borrow from her. I could spin my novel into a brisk orbit around the dark gravity of a suspicious death. I could create a limited group of suspects. I could fill the book with menace and motives.

Back then, I thought the most important part of any whodunit was that first syllable: who. So I built the vital events: who died, who was injured, who was guilty, every permutation of who. I had the scaffolding of my mystery. This structure would sustain and support everything else.

But although I had the who, I did not yet have the where. Gradually, I began to understand that where _is a vital factor in any mystery — perhaps the most vital. _The Murder on the Orient Express would be nothing without its train, hurtling through snow in the darkness. And Then There were None would be nothing without its isolated island, populated by the damned.

So I thought. I wondered. I spent more time with Miranda. I figured out that The Lightkeepers would be written in the form of letters to her long-dead mother. I roamed through her childhood, her past relationships, her study of photography. For me, research does not always involve active searching. I knew what I needed — the perfect place to hold my story — but I did not yet know what that might be. I tried different options in my mind. The arctic? No. The rainforest? No. An urban setting? No. Nothing seemed to fit.

Then, at last, a friend gave me a copy of The Devil’s Teeth by Susan Casey. This kind of thing happens to me a lot. I often write about nature, which means that people give me books about nature, which inspires me to write more about nature. It’s the most wonderful kind of vicious circle.

From the start, The Devil’s Teeth grabbed me by the throat. It is a strange, wild memoir about a strange, wild island chain. The Farallon Islands lie thirty miles off the coast of California. A wildlife refuge, the place is inhabited by sharks, whales, seabirds, seals, octopuses, and fish — every conceivable form of marine life — as well the biologists who study these creatures. There are few places left on Earth that remain so untamed and raw. There are few settings for any book as isolated and enclosed as the Farallon Islands.

It is hard to describe the sense of completion I felt upon finishing The Devil’s Teeth. Everything made sense now. I had the who, I had my mystery, I had my plot, and at last I had the where. Agatha Christie had shown me how to build my structure. Now Susan Casey had given me my setting. Out of mysteries and memoirs, The Lightkeepers was born.

+++