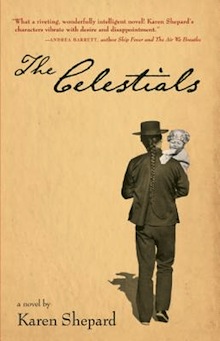

Our Research Notes series invites authors to describe their research for a recent book, with “research” defined as broadly as they like. This week, Karen Shepard writes about The Celestials (Tin House Books).

+

So. Photographs. They seem to be something I return to again and again in my fiction. My first novel was based loosely on Sally Mann’s controversial portraits of her own children, and my most recent novel not only relied on photographs during the research process, but uses some of those photographs within the text.

So. Photographs. They seem to be something I return to again and again in my fiction. My first novel was based loosely on Sally Mann’s controversial portraits of her own children, and my most recent novel not only relied on photographs during the research process, but uses some of those photographs within the text.

Of course, the use of photos means different things to me now than it meant during the process of writing. But in retrospect, the use of photos makes a kind of emotional sense in terms of my particular weirdnesses, needs, and desires. I’m the only child of parents who were, at best, enigmatic, and at worst, impenetrable. Reading their faces became a useful skill, a way to access the subterranean by way of the overt. And as others figured out long ago, it’s not a bad skill to have as a fiction writer either. We writers believe in the power of the implied, and photos are filled with implication, especially in terms of character and desire.

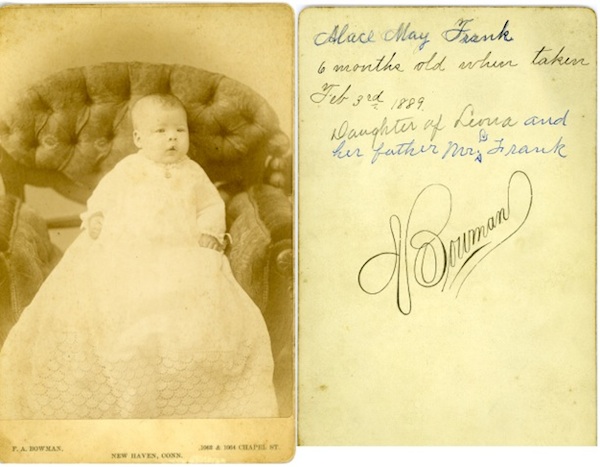

The Celestials is based on an historical event. In June of 1870, seventy-five Chinese laborers arrived in North Adams, Massachusetts, to work for Calvin Sampson, one of the biggest industrialists in that factory town. Except for the foreman, Charlie Sing, they didn’t speak English. Most of them were under twenty-two, and none of them knew they were strikebreakers. The novel reimagines Sampson’s “Chinese experiment” and the effect of the newcomers on the New England locals. When Sampson’s wife, Julia, gives birth to a mixed-race baby, the infant becomes a lightning rod for the characters’ struggles over questions of identity, alienation, and exile.

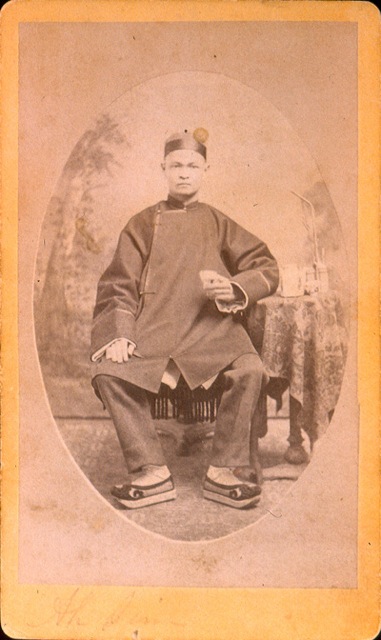

In The Celestials, the photographs that formed a huge part of my research were doors into the emotional state and stakes of my characters. One of the first things Sampson did was have a group portrait of the Chinese taken. In addition, many of the Chinese spent a significant part of their salaries on individual portraits during the ten years they lived in North Adams. Charlie’s descendents shared family photos with me as well as some photos they’d never been able to identify. The way all of these people had chosen to present and preserve their self-images fascinated me, and I knew that those images would somehow be integral to my telling of the story.

At first, that use just involved descriptions of portraits, but that began to seem like not quite enough, a little like describing a character’s artwork or poetry without showing it. So I started to play around with using the photographs in the actual text. I took as a model the way someone like W.G. Sebald used in his work visual images as an additional, if somewhat enigmatic, exploration of the characters’ interior life. I wanted, I think, the reader to have the experience I was having, and the experience I imagine many of the local townspeople had in relation to these workers. I began to think of those workers as the shepherding ghosts of the story, with all the associations that ghosts contain.

I wanted them to seem to be the catalysts for all these events, yet still sometimes largely forgotten, or undifferentiated, by those people most affected by their presence. The townsfolk, the media, and Calvin Sampson himself often referred to the Chinese as the boys, or the workers, or, even more problematically, our boys, or my boys. I wanted the reader, after encountering such notions for a while, to be reminded visually of these workers as individuals.

And I wanted the reader to feel that they weren’t just gawking but also being watched themselves. I certainly felt the responsibility of history’s eyes on me, and I wanted to replicate that for the reader, to somehow explore our responsibility to our relationship to the past.

And, of course, I was also drawn to the photos as a resurrection. This episode in history has been largely forgotten. Only two of the workers stayed in town after 1880. I imagined the photographs working much the way the wrecked train and its passengers work in Marilynne Robinson’s Housekeeping: the disappeared who are still present, influencing us all in ways we may or may not be willing or able to understand. In that regard, there were many photos that were imaginative springboards that I did not reproduce in the novel, but that remained present as relevant ghosts nonetheless.

So herewith I present some of the photos that mattered most to The Celestials paired with parts of the novel that those photographs inspired.

+

Two blocks away, Sampson was issuing more orders, this time to William P. Hurd, local photographer, who was setting up his glass-plate camera and heavy tripod on the factory’s south lawn, making ready for a photograph for which Sampson had generated plans shortly after the Chinese had embarked from California. He stood in the evening sun, checking and rechecking the contents of his portable darkroom — chemicals, trays, and plates piled in the back of a covered wagon led by his astonishingly aged chestnut mare.

Once The Celestials had disappeared into the factory, the accompanying crowd had, save but one or two lingerers, dispersed, and these last few took no note of the man poking around in the back of his wagon. They did not attend to his positioning of his stereo camera — two plate cameras situated on a single mount — or to his worried checking of the falling afternoon sun. Yet the lingerers were rewarded for their loitering when Sampson ushered the seventy-five Celestials out the back door of the factory and spread them across the south wall of his formidable brick building.

The boys were baffled. They had not even had time to change out of their travel clothes or wash their faces. The tea water had been put on but not poured, and more than one of the boys fretted as he was arranged among his fellow travelers that the cooks had forgotten to remove the kettle and the water was, at that moment, boiling away.

The photographer had placed his camera too close, and the group had to wait as he retreated in order to accommodate the size of the gathering. Sampson muttered that he had paid Hurd to be ready, not to watch him make ready, and Hurd, burdened with tripod and camera, promised to be as quick as possible.

“What are they saying?” the youngest of the boys asked Charlie.

“They are fighting,” Charlie answered. “It is not about us,” he added, and the boy seemed reassured.

The low light meant that the exposure time was long. Sampson paced behind the camera, and Hurd agonized that the man’s tread was making the camera tremble in minute but disastrous ways.

The photograph would be, as most of Hurd’s work was, lacking, and the many magazines looking for images of the Chinese in the months following their arrival would not choose this one, a fact that bothered not only Hurd but Sampson as well. What was the point of having gone to this expense to show the world what he was up to if the world would not look? But the world is looking, Julia would remind her husband, fanning the illustrated newspapers before him. Just not at your photo, she told him. Exactly, he replied, closing the discussion.

But the Chinese boys, stiff and tired from their journey, hot against the American bricks in their dusty clothing, would remember the photograph more than they would remember anything else from that day. For most of them, it was the first time they had sat for a photograph. There was confusion and wariness about their new employer’s reasoning. Was there to be a display on the factory walls?

+

On August 18, she accompanied the initial group of Celestials to the first of their photographic sittings. Standing there in William P. Hurd’s studio, the August air as thick outside as in, Charlie hushed and herded the first group of five boys. It had not been difficult to persuade them, though he had been able to offer no clear explanation of their employer’s motivations. No one could say why husband and wife Sampson wanted all seventy-five of them to sit for individual cartes de visite. It was impossible to imagine to whom they could conceivably offer such cards. But once they’d been assured that the almost two-dollar sitting fee — more than twice their daily earnings — would be paid by the Sampsons, they had agreed that it seemed prudent to give the man upon whom their livelihoods depended what he seemed to want.

There was no distinguishing between Sampson’s desires and those of his wife. Mrs. Sampson had been in the last week more and more of a presence, insisting that Charlie impress upon the boys that they were to dress in their favorite clothes and bring with them an assortment of their possessions. Perhaps a favorite book or keepsake. She had seemed to have not the slightest idea what those things might be. Charlie concluded that although it had been Mrs. Sampson who had come to the factory to make the request, she was acting as an emissary for her husband, who perhaps hadn’t had the time to do so himself. The notion that the photographs were an idea hatched from her own mind was an even more baffling one and Charlie naturally turned away from the complicated, choosing, if he could, the path of least confusion, although he found himself unable to ignore all consideration of her. She was, he was coming to feel, a bewildering figure. Why had she appeared in his sickroom to read to him? Why had she continued to do so? Why had she not introduced herself as Mrs. Sampson? And why, perhaps most confusing to him, did these uncertainties not make him retreat to a self- protective distance?

But in Mr. Hurd’s studio, he noted that Sampson in no way seemed to be part of the endeavor. Mrs. Sampson expressed an enthusiasm for the objects the Chinese had brought that he found startling. She picked up Ah Har’s rice paper letter and asked Charlie if it was a letter from the boy’s family. She wanted to know if Chung Him Teak had carried the scarf with him on this whole long journey from home. If Sam Toy had carved the dragon himself. If many of them were talented in this way.

Charlie shrugged politely. Usually, this kind of hysteria made him shut down, close as many of his watertight doors as possible, but in Mrs. Sampson, he realized with some mystification, it made him want to coo at her until she stilled and calmed.

She teased him gently about falling short of his responsibilities. “Do you know them not at all, Mr. Foreman?” she asked, turning back to the treasures before her.

He had grasped enough of overheard conversations at church and Sunday school and the factory to know that the town’s opinion was that Mrs. Sampson was delicate and shy, so he remained without speech, set off-balance by her apparent self-confidence. He would never know anyone to go from anxiety to sureness as quickly and as often as he would come to learn that she did.

Even then, he was beginning to understand that she was, as he was, willing to offer others what they most wanted to see. He would never fully grasp that this was not something held in common only between them, but a trait shared the world over.

She was right, he thought on that August afternoon. He knew none of the boys’ stories. He was not even confident of all their names. He could not have listed their home villages. Was this something he should be working to remedy? It had never occurred to him. Because, of course, Charlie shared the guilt of everyone who had ever referred to the boys as Sampson’s workers, the Boys, the Chinese, The Celestials. How wrongheaded to think that seventy- five individuals could be defined by one or two words. And how much of that wrongheadedness had been encouraged by that first stereograph Sampson had commissioned. Every visitor to the factory who passed by the outer wall to Sampson’s office also passed by that stereograph: a mass of dark-haired boys dressed in dark clothing and topped by dark hats. Perhaps Charlie was thinking of that image and feeling the wince of self-recrimination as he recalled his role in arranging the boys into their lines and in reassuring them that nothing of note would come from this. For whatever reason, as Hurd welcomed him into the portrait chair and gave him simple instructions, Charlie glanced up at Julia standing with the five boys behind the camera, not smiling, simply watching, and as he met her eyes with his own, he had the terrifying impulse to tell her about himself. Not the version he had given to the Methodist congregation, or to Mr. Chase, or to the immigration officer years and years prior, but everything he knew about himself and his life thus far, everything he understood, as plainly and clearly as he knew how to tell it.

As Hurd finished his instructions, and the small sounds of the Celestial boys around her ceased, their attentions turned to their foreman in these peculiar circumstances, Julia felt an unfamiliar anticipation. It suddenly seemed to her the most intimate of situations, to be here on one side of the camera viewing someone on the other. She felt as if she and Charlie were sitting for some larger portrait, as if they occupied an upstairs room of an intricate dollhouse and an unseen camera peered at them through the tiniest of windows. A small tremor passed beneath her skin.

Hurd told Charlie to hold still and assume a pleasant expression. Julia noted his attempts to follow these instructions, and for the six seconds that Hurd removed the cap from the lens, she and Charlie held each other’s gaze, neither of them feeling as if they should look away.

+

When Lucius Hurd arrived at his South Adams studio to open up shop on that overcast August 1, the Chinese foreman was standing by the door, waiting. Mr. Hurd had on one or two occasions been visited by the Chinese, but his studio was smaller and less convenient than that of his older brother, William, and situated in the decidedly more rural South Adams, and Lucius Hurd prided himself on what he would describe as a more dignified approach to promoting his work. His wife found this streak of passivity to be his tragic flaw, the source of all their unhappiness and continued struggle. Too good for his own good, she told their eldest daughter. Certainly for mine, she often added.

And so the sight of the Chinaman, worn and bedraggled as he was, was a welcome one, and Lucius attempted to convey as much in his cheerful greeting.

The Chinaman seemed not to notice, and Lucius had the distinct sense that if he had never succeeded in unlocking the door, the man would’ve expressed nothing but content- ment at standing outside the building for the rest of the day. About this, Lucius Hurd would have been wrong. Charlie’s insides were at war. His only chance at not falling to the ground in pieces was to make his outer body a lacquered shell within which the inner tumult could be contained. He knew this photographer not at all, yet he’d seen the portraiture he had made of a few of the boys. He knew of what kinds of transformations the photographer was capable with what had seemed to Charlie nothing more than the turn of two ankles, the confident spread of knees, a hymnal, and a silk fan. One or two of the boys, Charlie knew, had given copies of the photographs to their Sunday school teachers. Charlie had teased one boy about the gift, but the boy would not be teased. With an utter seriousness, he had said, “I give her a ghost image of myself so that she can remember the form from which the ghost comes.” He had indicated his body with a gesture of such fluidity that Charlie had been seized with shame and had teased him no more.

Lucius kept the curtains drawn and lit the lamp on his front counter.The Chinaman looked as if he’d slept outside, and clearly his hair had had an unsuccessful encounter with dull blades.

Charlie noticed him regarding his hair. “You can shave and trim?” he asked, pulling from beneath his tunic a small towel, which he opened on the counter, revealing a razor, some soap, a comb, and a pair of work scissors.

For Lucius Hurd this was proving to be a most remark- able day. He told the Chinaman that it wasn’t his usual trade, but he didn’t see why he couldn’t offer him a decent shave and cut. As long as the man wanted nothing fancy.

Charlie frowned. “Nothing fancy,” he repeated. He reached under his tunic and produced a small money bag from which he pulled one gold coin. “Best American portrait,” he said, putting the coin on the counter between them.

So Lucius Hurd would give this man a shave and a hair- cut. He would dress him in his finest costume suit. Perhaps even a hat. He would take the portrait. And then he would pass the rest of the day as he had expected to pass it. In the evening, he would close up shop and retrace his morning steps back to his home and his family, where he was sure that not even his wife could object to a hard gold coin placed in her small, beautiful hand.

+

By February of 1878, Charlie had gone, and by midsummer, he and Ida had wed. He did not feel her to be a consolation prize. He felt, as he tried to make clear to her, that someone had taken his face between soft hands, turned it from the window through which he had been looking for so long, and said, merely, Look. Over here. There is much to be seen. The fact that he had not looked in this direction before, he told her on the night before their wedding, was the fault of the viewer, not the view.

At the small Baptist church that she had first attended as an infant in her mother’s arms, she and Charlie stood before God and her family, and Ida marveled at her lack of nerves. Truly, she thought, she had never known a man like this one.

Alfred was witness to the marriage. He stood in the last row of the airless one-room church barely able to contain his gall at her choice. And so Charlie was glad, when he and Ida decided to move back North — to escape her still- angry family for what they hoped would be the more toler- ant anonymity of New York — to be leaving Alfred behind.

Lucy, too, had been to the wedding, and seeing her there sharing space with Charlie in God’s small room had settled something for Ida, and she had felt lucky to have them both in the world.

In the early going, Charlie had been so sensitive to Ida’s anxieties that he had imagined his feelings for Julia written in bold characters on a long scroll and rolled tight, tied in red thread, and sealed with wax. It had given Ida and him enough space to find the materials to build their own kind of happiness, and although in the structure they made, Julia’s absence was always for him like a boarded-up window, it was nonetheless a place of sturdiness, filled with both warmth and breezes and many clean rooms.

+

Julia opened the windows in the bedroom and the front parlor as wide as could be managed. The August heat was breaking and an evening wind had found its way through the street. The sounds of Saturday rode through on the wind’s back.

She did not worry: the baby had already proved herself a champion sleeper.

She lowered herself onto her side next to her infant. The chest rose and fell in the movement of rapids over river rocks. Normal, Julia’s sister had said. Julia still barely believed it.

Outside, the sun lowered, and evening blanketed the town. The hoots of children subsided. The whip-poor-wills and grosbeaks began. Somewhere, someone was cooking something delicious. Somewhere else, fertilizer was being spread.

Her senses were like no previous acquaintance. They were the ropewalker’s cable she had been witness to as a child, high and taut beneath the canvas roof of a circus tent. She

tucked her hands beneath her cheek and continued to regard her girl. I could stay here for all time, she thought. She understood herself to be free of exaggeration’s grip. Her world was now her body, the girl’s, and the circle they fashioned together. These were her feelings, simple and plain.

Photos courtesy of Private Collections and North Adams Public Library

+++