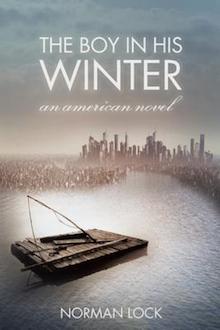

Our Research Notes series invites authors to describe their research for a recent book, with “research” defined as broadly as they like. This week, Norman Lock writes about The Boy In His Winter from Bellevue Literary Press.

+

“I became a tourist on the Internet.”

— Huck Finn, in his 70s

To be asked to reveal the secret processes by which I conduct my research for the fictions I produce — fictions that are as necessary to my life as they are necessarily staged in places and times remote from it — is like asking a medium to expose the invisible wires and hidden gramophone (to speak antiquely) with which she creates her illusions or the alchemist to disclose the transubstantive art by which desire is materialized, if only in base metal. (That’s a gaudy metaphor, surely, but illustrative of my belief that words can be woven into nets of syntax to ensnare the mind’s ghostly movements.) But having been asked, I will try to write sensibly of the conscious ways I research my narratives — in particular, the new novel, The Boy in His Winter.

To be asked to reveal the secret processes by which I conduct my research for the fictions I produce — fictions that are as necessary to my life as they are necessarily staged in places and times remote from it — is like asking a medium to expose the invisible wires and hidden gramophone (to speak antiquely) with which she creates her illusions or the alchemist to disclose the transubstantive art by which desire is materialized, if only in base metal. (That’s a gaudy metaphor, surely, but illustrative of my belief that words can be woven into nets of syntax to ensnare the mind’s ghostly movements.) But having been asked, I will try to write sensibly of the conscious ways I research my narratives — in particular, the new novel, The Boy in His Winter.

This “American novel,” as I have subtitled it, signifies my intention to consider the present — its ambiguities, monstrosities, and miseries — in light of the American past or its imagined future, in a series of books. To this end, I recreated Huck Finn as a time traveler who, having fetched up on the distant shore of 2077 (after 170 years in mythic time spent rafting down the Mississippi as a boy of thirteen), is afforded a long backward glance at the nineteenth, twentieth, and twenty-first centuries. That the novel manages a fair amount of comedy is likely due to Twain’s wry voice, whose echo I heard while writing it.

Because this novel — like The American Meteor, which will follow in 2015, and indeed everything else I have produced in prose, verse, and drama since the 1970s — was written about places and times mostly unfamiliar to me, research was necessary; is, in fact, imperative for works that refuse the contemporary and the nearby in favor of the faraway and the past (or, in some instances, the future). One might rely entirely on the imagination to create the fictional landscape, a reliance evident in my A History of the Imagination and Land of the Snow Men, whose Africa and Antarctica, respectively, were, by and large, figments. But if my intention is, as it is now, to devise stories that will mourn what has been lost in the pursuit of civilization’s advancement, corporate enrichment, and personal aggrandizement — if I hope to be, in my “American novels,” a moral writer (without, however, being either a moralist, a prig, or a bore), then the landscapes and the events that unfold within them had better be “real,” if anything can be said to be real in a world of slippery surfaces and treacherous appearances. Invention will not suffice — not entirely and not on its own; ransacking memory’s drawers will not suffice; one must consult sources to get the history and the scenography right. The book’s reality needs to be a recognizable one.

My primary sources in the writing of The Boy in His Winter were, for the novel’s Part One, Twain’s own novel (which I nevertheless chose not to reread) and Ken Burns’s The Civil War; for Part Two, my past career as an advertising copywriter for the yacht, superyacht, and sportfishing businesses and the “literature” I produced for them; and for Part Three, my Dutch friend Marco Knuaff, living in Papendrecht, my memories of the Santa Monica Pier, and the children’s picture book I wrote long ago, I Looked out the Window and Saw a Giraffe.

My secondary sources were equally important in my pursuit of realism: Wikipedia, which has replaced the Funk & Wagnall Encyclopedia I used prior to the Internet, and Google terrain and satellite maps. What an extraordinary gift to sedentary writers without means or time to travel are these online maps and virtual tours! Using them, I can visit Vicksburg’s bluffs, Port Eads’s lighthouse and fishing camps, Richmond’s wharfs, Panama City, St. Lucie Inlet, Kill Devil Hills, Little Egg Inlet, Great Bay, Goose Cove, Gran Canaria, Papendrecht, the Hooghly at Konnagar, the Rhine Gorge, Santa Monica, the Perfume River, and Hannibal; see them and — with the Internet to instruct me in the sound, smell, light, weather, flora, fauna, and mineral composition of places otherwise inaccessible to me — possess them sufficiently to make them my own on paper.

+++