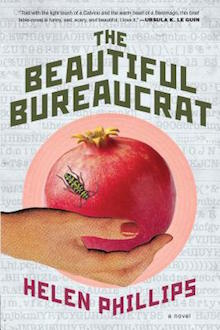

Our Research Notes series invites authors to describe their process for a recent book, with “research” defined as broadly as they like. This week, Helen Phillips writes about The Beautiful Bureaucrat from Henry Holt.

+

1.

First, the title. A pair of words, Beautiful, Bureaucrat: dropping into my mind as I sat at my desk during data-entry season at my job, feeling most unbeautiful, feeling jealous of the people whose names I was typing into the database, those who were probably out and about in the world, in the sun, drinking coffee, laughing. Beautiful Bureaucrat: a contradiction content-wise (bureaucrats are mousey), but a duo form-wise (the alliteration, the “eau”). The title, arrived full-formed, before I knew a thing about the book (not my experience with my previous two books, whose titles were hard-won and arrived late in the game).

First, the title. A pair of words, Beautiful, Bureaucrat: dropping into my mind as I sat at my desk during data-entry season at my job, feeling most unbeautiful, feeling jealous of the people whose names I was typing into the database, those who were probably out and about in the world, in the sun, drinking coffee, laughing. Beautiful Bureaucrat: a contradiction content-wise (bureaucrats are mousey), but a duo form-wise (the alliteration, the “eau”). The title, arrived full-formed, before I knew a thing about the book (not my experience with my previous two books, whose titles were hard-won and arrived late in the game).

Only seven years later would I discover that in a letter Allen Ginsberg once referred to Kafka as “the beautiful bureaucrat.”

+

2.

Second, a hundred-page list of images. Gathered over the course of two years of my life, researching the self, the experience of being tired, the experience of being pregnant, the experience of walking around a city, my fragmented thoughts, typed but not quite coherent.

+

3.

Third, a curiosity about population statistics. The census has always intrigued me. How do we humans keep track of ourselves? How many of us are there? How many of us have there ever been? Kathryn Schulz’s piece “Final Forms” in the 4/7/14 issue of The New Yorker: “The flip side of democracy is bureaucracy: If everyone counts, everyone must be counted.”

+

4.

Fourth, a study that a college professor mentioned in my intro to psychology class: A personality test was given to a lecture hall of students. The next week, each student was handed an envelope with a personality description based on his/her responses to the test. The students were then asked to rate how accurate the description seemed to them. The students found the description overwhelmingly, even heart-wrenchingly, accurate.

But they had all received the exact same personality description.

Bertram Forer, “The Fallacy of Personal Validation: A Classroom Demonstration of Gullibility,” published in 1949 in The Journal of Abnormal and Social Psychology.

+

5.

Fifth, the names. Long, long lists of names. Generated from a baby name book I’ve owned since I was seven (I begged my babysitter to buy it for me when I noticed it at the grocery store check-out). Generated from any publication received in the mail that involved lists of names — union bulletins, alumni magazines. Generated from the internet — the search for common surnames, for rare surnames, for surnames that start with X.

+

6.

Sixth, Green-Wood Cemetery in Brooklyn. “Founded in 1838 and now a National Historic Landmark, Green-Wood was one of the first rural cemeteries in America. By the early 1860s, it had earned an international reputation for its magnificent beauty and became the prestigious place to be buried, attracting 500,000 visitors a year, second only to Niagara Falls as the nation’s greatest tourist attraction.” I needed to know the names of its paths, the names of its residents. I stand in awe of the Cemetery’s online name search function.

+

7.

And then, seventh, uncountable day-in, day-out random research questions. What year were typewriters invented? What are the ingredients in “kitchen sink” cookies? What is the exact wording on the United States Postal Service’s failed delivery receipts? Is “pank” an actual color or was that just something my mom said in the 80s? God bless the internet. How did writers manage in the olden days?

+

+++