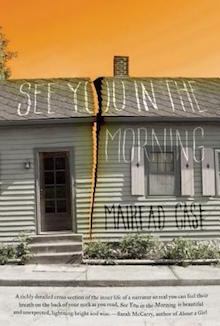

Our Research Notes series invites authors to describe their process for a recent book, with “research” defined as broadly as they like. This week, Mairead Case writes about See You In The Morning from Featherproof Books.

+

I wish that publishing my novel See You In the Morning means I know how I wrote it, or how to write the next one, but truth is I’m not really sure. Writing a book is work different than following a map; it’s much closer to driving cross-country at night with one headlight working. Book-writing is not a romantic experience, and anyway if it was I wouldn’t trust it.

I wish that publishing my novel See You In the Morning means I know how I wrote it, or how to write the next one, but truth is I’m not really sure. Writing a book is work different than following a map; it’s much closer to driving cross-country at night with one headlight working. Book-writing is not a romantic experience, and anyway if it was I wouldn’t trust it.

But that’s not a frustrating feeling — in fact it’s hopeful because if I did it once, I can do it again. And I don’t mean that in an “I will run the marathon again next year”-kind-of-way either. Rather, for me writing longform fiction is a contemplative practice. Doing it well — by which I mean: writing real, complicated characters existing in space and time — requires time and space too. Having health care helped me write this book. So did a home office with a door. And going to metal shows so loud my clothes shook, then walking home alone in the cold quiet bright. I wrote a lot of See You In the Morning on a red chair underneath a quote from Fanny Howe’s essay “Bewilderment.” In it she mentions the Sufi prayer that says, “Lord, increase my bewilderment.”

“This prayer is also mine,” continues Howe, “and the strange Whoever who goes under the name of ‘I’ in my poems — and under multiple names in my fiction — where error, errancy, and bewilderment are the main forces that signal a story.” Yes. I grew up Catholic and am still Catholic, though I’m much more lost and progressive than I used to be, so Howe calling this “prayer” is an easy fit for my own best loopy brain. But when I teach her essay, I ask the other writers in the room to find their own languages for bewilderment, and to think about how it works in their work. If there’s none, maybe the story needs some. This too is writing.

“A signal does not necessarily mean that you want to be located or described,” says Howe. “It can mean that you want to be known as Unlocatable and Hidden.” I thought a lot about this, writing See You In the Morning: what does it mean to read, to write characters we don’t immediately understand, or relate to? Characters who turn their backs or burn down the house or just don’t give a shit. That’s not a leading question. I’m asking. I want to write more of them.

I grew up in a family who let me dance alone in the hallway for hours, and talk to imaginary friends in public places for even longer, and called both wisdom. Yet my parents are also scientists, mathematical planners and outliners, so while writing the first draft sometimes I felt like a failure for not knowing what this book was about, or how it would end. Retrospectively this too was wisdom, not carelessness. Or laziness: it’s really hard to stay at the desk, for any number of reasons, and especially if you are a person who likes being in the world. How do you write a book? Keep your butt in the chair.

But, okay: mysticism aside, here are works of art that helped me write transitions and images in See You In the Morning:

- the knots in Hito Steryl’s Lovely Andrea: how beautiful they are

- the unveiling of the Wizard in The Wizard of Oz: how that jolt makes us care less about him, more about Omaha (which is my hometown too)

- the metaphors in Nami Mun’s Miles From Nowhere: how they are real and occasional, not magical

- the instruments in Matmos’s The rose has teeth in the mouth of the beast: how physical materials can remix in homage (and danceability)

- the trees and birds in Bob Glück’s Margery Kempe: how they anchor the narrative

- the parade of weirdoes in Clowes/Zwigoff’s Ghost World: how Enid and Rebecca see everyone, how everyone is real

- the dots in Yayoi Kusama’s art: how they make a calming white noise

- the work of E.L. Koingsburg: how she made me want to be a witch, to care, and to go to museums by myself

- the colors in Hans Scheirl’s Dandy Dust, the colors in Polly and Digory’s rings in The Magician’s Nephew, the glitter in Marilyn Minter’s paintings, the nail polish aisle at the drugstore: color is story too

- David Wojnarowicz’s burning house stencil, Mike Kelley’s Catholic Birdhouse, Gordon Matta-Clark’s Splitting: how I wrote underneath these three images, and tattooed one of them onto my right wrist. Home is where

The concept of prayer — which for me connects to vulnerability, homes, magic, stars and forests and the ocean — is religious in the sense that it re/aligns, and it allows me to hear my characters better. What do THEY want? Who cares what I want them to want. If they are not real they are boring. In my thesaurus the antonym of prayer is demand. In my mind if I pray then I am not god, which is a relief. Because I am not god. I doubt. I do not go to church very much, but I think about it a lot. So anyway, finally I finished this book, changed the images on my desk — not the little stone animals though; those buddies stay — and started writing the next one.

+