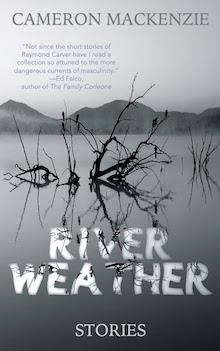

Our Research Notes series invites authors to describe their process for a recent book, with “research” defined as broadly as they like. This week, Cameron MacKenzie writes about River Weather from Alternating Current.

+

The Cheap Laugh

Edward P. Jones once explained his relationship to his characters by saying that he was the god of the people in the book.

Edward P. Jones once explained his relationship to his characters by saying that he was the god of the people in the book.

It’s rare, I think, for a writer to be so direct about the degree of control they might exert on their own imaginary creations in order to bring off a story. James Joyce of course said the writer should be removed and disinterested, paring his nails. People will tell you that Joyce wrote that way because it suited him; it was the best vehicle for him to say what he wanted to say. But in fact Joyce put that line in the mouth of one of his fictional characters, an endearing and egomaniacal kid, based not a little bit on himself.

I’ve written a book that is about my life. This wasn’t completely intentional. It’s a story collection put together over many years, and every time I sat down to write a story I was just trying to come up with something compelling and honest to say. The only way I knew how to do that was to use things that had happened to me. Maybe I’d do it differently now, maybe not.

But when you’re mining your own life for raw material it can be difficult to establish the precise amount of control you have over characters, settings, and events. I was always trying to determine where the truth lay in every scene, and I often struggled with the question of whether that truth lay in the past I’d actually lived, or in a fictional world I would have to lay overtop.

There’s something very interesting about how the labels of fiction and nonfiction affect nothing so much as the reader’s expectations. Of course the simple act of remembering is shot through with mediation, much less the crafting of those remembrances into something whole. Perhaps the reader expects to be told something real in nonfiction, or something true, but in that case I guess I don’t know what fiction is expected to do. When I try to write nonfiction it comes out… fine.

But I’ve found that when I totally make something up I tend to overdo it. I make it too big or too flashy, too dumb or too obvious. Facts help keep me in the realm of the believable. And so when I was trying to write these stories I always started with facts, then I gave myself the freedom to twist. Often I turned a montage of memories into a single coherent scene — very much like a dream — and then I built up something completely different on top of that groundwork. That was when I felt the most like a “writer” — not when I was remembering actual events, but when I was trying to catch and describe the reality I’d put into motion.

I’ve got a scene in my story “Kalim Mansour” where the teenage protagonist (based on me), gets into a complicated flirtation with an older woman at a car dealership. The origin of the scene was a trip I took with my dad to buy a car when I was a kid. But the character of the older woman and the tone of the story’s exchange was a result of conversations I’d had with two women I’d known. The first was a friend of my mother’s who began to flirt with me when I was about 13 or so. I remember I didn’t understand the tenor of our conversations, as though I was in the midst of an engagement where I’d never been told the rules. It was fascinating, but unsettling.

The second woman actually worked at a car dealership. I met her in my early 20s, and she was flirtatious as well, but also a very angry person; a person who liked to push the envelope in all aspects of her life. She once told me a story about how she gave a blowjob to a man in a job interview, not because she wanted the job, but just because she felt like doing it. I didn’t use that story — I don’t know if I could convincingly write it — but I combined that attitude with the conversational tone of my mother’s friend, and the character of my story just flared into life. I let her speak, and I let my protagonist respond. The scene was fun to write; it’s still fun for me to read.

When you’re trying to make fiction out of your life, what parts do you take and what parts do you leave behind? How much do people really need to know about my mother or my sister? Should I tell the reader everything I felt at a given moment, or would the character based on me really feel the same thing? What if he didn’t?

In the car dealership scene I just mentioned, I originally wrote the conversation with responses that I would’ve given to a threatening, cajoling, seductive older woman. The exchange, however, was flat. The woman wasn’t being challenged enough; she had too much control. The character sparkled, but the scene didn’t sparkle. So, I simply changed one line so that my protagonist began to push back, and then I watched as the woman was caught off-guard, and then amused. I quickly rewrote the dialogue, that one initial change affecting the entire tenor of the conversation. It changed the scene, and the scene changed the story.

Perhaps the most interesting thing about this process is how little control I felt I was exerting. I was neither the god of the people in the story, nor was I removed and paring my nails. It was like I was watching someone else write the scene, or rather, I was watching characters I had created play out the scene. I was certainly there, but I was absent in some very important sense: the intentional me was absent, the part that overdoes it or goes for the flash or the cheap laugh. I’d set up the proper conditions for the part of me that really knows how to write to, for just a little bit, take over. Maybe that’s what Jones and Joyce are talking about; I’m not sure. But when I come up with something like that it feels more real, to me, than any nonfiction I could ever put down.

+++