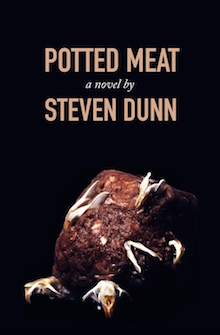

Our Research Notes series invites authors to describe their process for a recent book, with “research” defined as broadly as they like. This week, Steven Dunn writes about Potted Meat from Tarpaulin Sky.

+

Potted Meat

Potted Meat

is two-fold, the first being a symbol of poverty. Secondly, it was always interesting to me how the label on a can of Potted Meat presents itself as gourmet, but when you read the ingredients and open the can, there’s a different story. I did a lot of staring at an actual can of Potted Meat, listening to its essence: its assertion of sustenance, compressed ingredients, physical size and weight, etc. I wanted to look past the label and open that can (some lives in West Virginia) and really examine/taste/feel the ingredients.

Selah Saterstrom’s

novels The Pink Institution and The Meat and Spirit Plan shook the shit out of me. I said to myself aloud, “Goddamn, you can say this in a book?” So this was a lesson in trying to write the impossible. A lesson in being vulnerable. A lesson in getting out of the way of the work and letting it speak its dirt, ugliness, beauty, truth, lies, and whatever else it needed to say.

Rapper Nas’

album illmatic lived inside me since I was a child. And he celebrated and criticized his place in Queens, NY, and his place in it, which seemed to me like his place was always teetering on the edge of being inside/outside. He acknowledged a complicated mess, and put the reader in that mess. And he’s probably the best storyteller in rap because he offers a few details and big pictures bloom. “At night New York / eat a slice too hot / use my tongue to tear the skin / hanging from the roof of my mouth.”

Rappers Outkast’s

forms evolve within and between albums. They let things grow and decay, and give space to both through distorted vocals, whiskey-sounding guitars, songs from 95 beats per minute to 155, and the juxtaposition of Andre’s and Big Boi’s styles and concerns. This was a lesson in letting a story grow or decay into what it is, and to write it as such. A lesson in dissolving binaries and acknowledging the spectrum of things/people. And a huge lesson in self-acceptance, like sometimes I’m on some street shit, and sometimes I’m on some introspective-space shit. And it’s fine. The (human) (artistic) form can hold both and what’s in between and outside.

Correct/Proper Grammar

is a classist and sexist and racist social construct. Because I was conditioned in public schools and some parts of society, I thought books should be written like, you know, all proper and shit. (I’m being silly, but that phrase carries a lot of dismissive weight, ie: acting all uppity and shit.) How could I write a story about black people in West Virginia the way some high-class white man from long ago decided how we all should write and talk? Which I think is an important/empowering position for people of color: to say, fuck that, there’s intelligence, wisdom, and love in our language. Because we’re taught the opposite. And that’s a big part of the reason I think women writers and their stories are so important, because a lot of women are also saying fuck your rules, and writing from the body and finding the grammars necessary to speak. So that was a lesson in re-asserting my silenced and policed body. A lesson in being secure enough to write in my black-ass, country-ass West Virginia way.

My Privileges

gave me the time, space, money, and health to be able to write a book, and then pay for submission fees to try to get the book published, and fly to places to read, etc. I had the G.I. Bill, so I was able to afford the expensive private University of Denver, where I had access to professors and peers who were publishing novels, and access to other resources that I didn’t have prior. Also, as self-identified man, I haven’t faced the same criticisms about my book that I’ve seen women face who write similar material, such as “they’re just vomiting on the page” or “writing overly emotional crap through a thinly-veiled autobiography.” So this is a lesson in staying out of the “I’ve made it” zone that I see a lot. And realizing that even though I am a writer of color, I still have some unearned advantages. And a lesson in understanding that the work is more important than I am.

+++

He was born and raised in West Virginia, and after 10 years in the Navy, he earned a B.A. in Creative Writing from the University of Denver. Some of his work can be found in Columbia Journal and Granta Magazine.