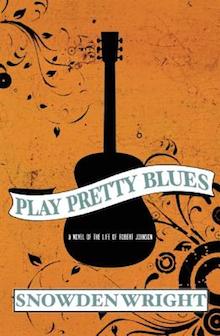

Our Research Notes series invites authors to describe their research for a recent book, with “research” defined as broadly as they like. This week, Snowden Wright writes about his novel Play Pretty Blues from Engine Books.

+

On June 15, 2000, in the Supreme Court of Mississippi, a hearing was held, the Estate of Robert L. Johnson v. Claud L. Johnson, regarding the latter’s heirship petition claiming to be the musician’s son. Claud had been told from birth his father was Robert Johnson. His birth certificate lists his parent as “R.L. Johnson, laborer,” seeming to refer to the influential bluesman — Grammy Lifetime Achievement Award winner and member of the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame — who supposedly sold his soul to the devil in exchange for his talent.

On June 15, 2000, in the Supreme Court of Mississippi, a hearing was held, the Estate of Robert L. Johnson v. Claud L. Johnson, regarding the latter’s heirship petition claiming to be the musician’s son. Claud had been told from birth his father was Robert Johnson. His birth certificate lists his parent as “R.L. Johnson, laborer,” seeming to refer to the influential bluesman — Grammy Lifetime Achievement Award winner and member of the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame — who supposedly sold his soul to the devil in exchange for his talent.

An elderly woman named Eula Mae Williams was called to the stand. At one point, the cross-examining attorney repeatedly questioned the veracity of her claim to have seen, in 1931, Claud Johnson’s mother making love to Robert Johnson. He asked, “You watched other people make love?”

“Yes, sir,” she said. “You haven’t?”

“No. Really haven’t.”

In response, the old woman looked at the attorney trying to shame her for having watched others make love and, referring to his claim to have never done so himself, said, “I’m sorry for you.”

I read those lines in the court transcript for the hearing. At the time, I was doing research for my first novel, Play Pretty Blues, a fictional interpretation of the life and death of Robert Johnson. Because I had finished with the easiest-to-find sources of information on the musician — the biographies of him, Peter Guralnick’s Searching for Robert Johnson, Elijah Wald’s Escaping the Delta: Robert Johnson and the Invention of the Blues, and Barry Lee Pearson and Bill McCulloch’s Robert Johnson: Lost and Found, being the most helpful — I had now moved on to some more direct means of learning about the legendary bluesman. I visited his possible graves throughout Mississippi. I read interviews with people who knew him. I listened to his songs constantly on my iPod. The court transcript was an exciting find. On reading how Eula Mae got her comeuppance on a condescending attorney, I grinned and thought, I am definitely putting this in the novel.

I did not put it in the novel.

Even though I wanted to tell the anecdote, no point in the narrative, not in the scenes closer to the present day, not in the summaries abbreviating the past, felt right for it. Ultimately the episode just did not fit organically. I nonetheless learned a valuable lesson by not being able to use it: Often the most effective research is indirect.

The parts of my research that regularly made it into the novel were those not specifically related to Robert Johnson. Play Pretty Blues is set primarily in the 1930s. In order to understand the world at that time, including not only how things felt, sounded, tasted, smelled, and looked but also, perhaps most importantly, what things were called, I read two kinds of books, those about the time period and those from the time period. Certain books fit both of those categories.

During the Great Depression, the Federal Writers’ Project, part of the Works Progress Administration of the New Deal program, commissioned the American Guide Series, a group of books with detailed histories on each US state. The books contained essays on each state’s culture, its arts and letters, its religions, its population, as well as on each state’s physical properties, its landmarks, its agriculture, its flora and fauna. Often the essays were remarkably well-written, as many writers soon to be famous were involved, such as John Cheever, Zora Neale Hurston, Margaret Walker, Saul Bellow, and Richard Wright.

The WPA State Guides to Mississippi, Alabama, and New York City were the most helpful to my research. In addition to being about 1930s America they were a product of it. As such they offered me both an immersive and an informative experience of the world in which my novel is set.

Other indirect elements of my research included reading a great deal of historical fiction and, to my knowledge, just about every single novel written in Play Pretty Blues’s particular point of view, first-person plural. Aside from helping me to learn the strengths and weaknesses of my novel’s genre forebears, those books, because they were fictional, provided me with an important lesson about my subject. If I follow the facts too closely, I might as well call it a biography instead of a novel, and if I don’t follow the facts closely enough, why even bother naming the character Robert Johnson?

That’s a lesson useful for anyone writing a novel based on historical facts. The research should always be beholden to the fiction. The fiction should not always be beholden to the research.

+++