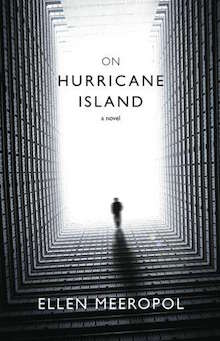

Our Research Notes series invites authors to describe their research for a recent book, with “research” defined as broadly as they like. This week, Ellen Meeropol writes about On Hurricane Island from Red Hen Press.

+

Researching torture in Maine

Standing in the security line at JFK Airport one day in 2008, I met my next main character. She wasn’t really there, but I saw her just the same. She had short gray hair, a no-nonsense attitude, an unusual occupation, an embarrassing name, and the bad luck to be plucked out of line and escorted barefoot down a side corridor by a TSA officer. My second novel, On Hurricane Island, was conceived.

Standing in the security line at JFK Airport one day in 2008, I met my next main character. She wasn’t really there, but I saw her just the same. She had short gray hair, a no-nonsense attitude, an unusual occupation, an embarrassing name, and the bad luck to be plucked out of line and escorted barefoot down a side corridor by a TSA officer. My second novel, On Hurricane Island, was conceived.

What I knew, in those first exhilarating moments of unrestrained imagination, was that Gandalf Cohen was an applied mathematics professor who studied hurricanes and lived in Manhattan with her lesbian partner. I knew that the TSA officer was taking her to a locked room, where federal agents would hood and cuff her and fly her to a secret detention center on an island off the coast of Maine for “enhanced interrogation.”

Writing this book would be challenging. A literary thriller, it was totally different from anything else I’ve written and would require different kinds of research. In 2008, I knew little about national security and nothing about torture, other than what I read in the newspapers or saw on television or in nightmares. But that’s where Gandalf Cohen was headed and I wanted to follow her. I don’t write with an outline, so I wrote the first draft relying on imagination and fear. Then it was time to do my research, to correct the worst of my errors of invention and fill in the many knowledge gaps.

Some research was already done; I had my setting, one I’ve used before. When I started writing fiction fifteen years ago, I worked at a wooden table in a red cottage on Vinalhaven, staring across a narrow sound to Hurricane Island. In my first novel, House Arrest, and in several short stories, I transformed the Fox Islands of Penobscot Bay into the imaginary Three Sisters Islands. I read books about the Maine islands in the past and present. I spent hours in Vinalhaven’s small but amazing historical museum, researching the history of the Fox Islands, the quarry industry and the European workers imported to cut the stone. I filled notebooks with jottings about rocks and quarries and plants and families.

In the novel, a major hurricane hits the island; luckily my husband is an amateur weatherman, giving me easy access to the lingo of back door cold fronts, wind patterns, and eye-walls.

But critical details were missing. The first draft contained a scene in which a character grabs a gun and hits somebody with it. That scene didn’t even convince me. I had never held any firearm and I needed sensory details to make it real. I wanted to describe the feel of the gun, the heft and texture of it. This required a trip to a local gun store, an experience I’ve described elsewhere. I will only add that my field investigation into gun culture was both illuminating and terrifying.

I knew nothing about secret detention centers. I’d heard rumors that civilian camps were ready to imprison and interrogate domestic dissidents, but had no idea whether there was any truth to the rumors. I write fiction and don’t have to document or footnote secret prisons in order to imagine them. But I needed the authentic details that would create a realistic world for my characters and my readers. And I couldn’t help being intensely curious about whether non-combatant extra-judicial prisons existed. Certainly the historical example of internment of U.S. citizens of Japanese ancestry was a sobering one, as well as the detention of undocumented immigrants in our contemporary landscape.

By far the hardest research was into torture. I read first-hand reports. I interviewed people at the Center for Constitutional Rights, where my daughter Rachel works as a staff attorney. I read Jane Mayer’s The Dark Side and that led me to portions of the military SERE manual (Survival, Evasion, Resistance, Escape). I learned details I wish I didn’t know — about the use of cold boxes, about loud misogynist music and the role of humiliation, about immobilizing people in uncomfortable positions for many hours. About preferred methods of slicing clothing from the body.

If I were researching and revising the book now, in the wake of publication of the Senate Intelligence Committee Report on Torture, I’d have access to more documented details about torture techniques than I could ever use in a dozen novels. I purchased the report, but I must admit that I can’t bring myself to read it. I don’t want or need more details about torture.

I’m not sure if the publication of the Senate documents now, as my novel launches, is serendipity or chilling. Both, perhaps. Serendipity because the topic is in the news, on our minds, discussed around dinner tables. Chilling because our national shame isn’t just fiction.

+++